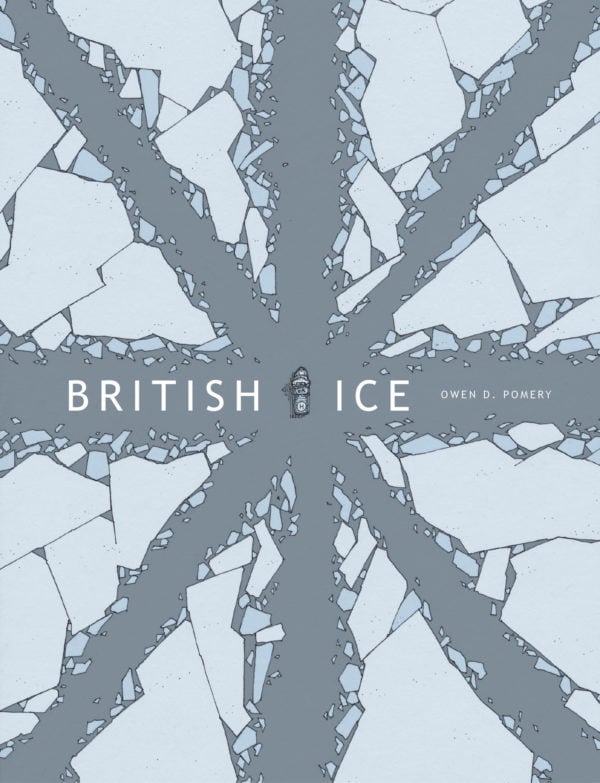

British Ice

By Owen D. Pomery

Top Shelf Productions

There’s a moment half-way through British Ice, Owen D. Pomery’s story about anger in a fictional British Overseas Territory, when Harrison Fleet, the new commissioner of Reliance Island — a.k.a. the British Arctic Territories — opens up about his own childhood and its relevance in the hostility he now faces from native Inuit inhabitants of the island. Fleet’s father is a legendary British ambassador to an atoll in the Indian Ocean and a specific, ugly incident during his service there has shaped Harrison’s view of his homeland and his service to it.

“How distorted is memory?” Fleet asks. “How much is it formed by those who form us as people?”

These are prescient questions, and as Fleet asks them, they seem to refer only to his experience as a member of the remnants of the British Empire. In fact, they go much wider, well into the 21st Century as so many of us find ourselves face-to-face with our own place in historical oppression. But they also refer to the victims of that historical oppression and specifically ask how much of their resentment has been shaped by the emotions of their ancestors. In other words, are we prisoners of the world views of our ancestors? As long as we cling to their narratives as our own are we destined to clash with those who cling to the opposite narratives? Do we need to let go of our emotional genealogy in order to move forward?

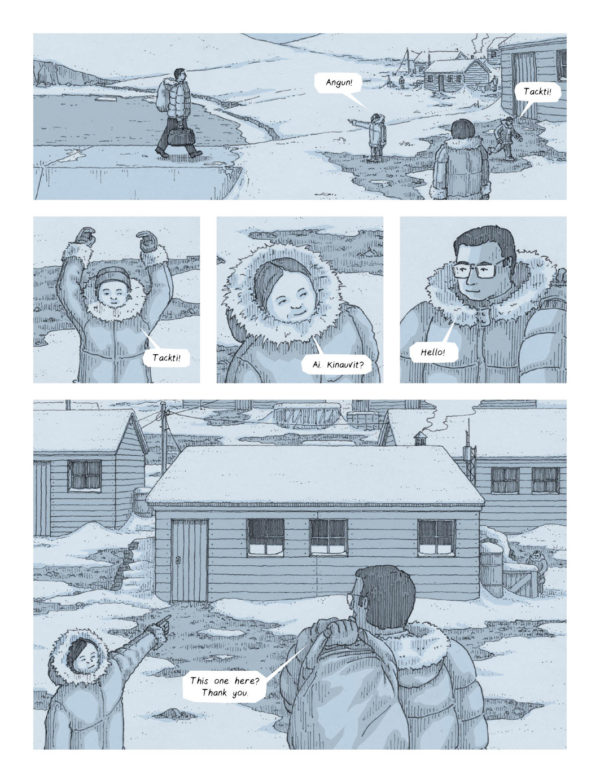

In British Ice, Harrison Fleet is about to collide with the real-world manifestations of these questions, and they speak strongly to why no one lets go. As the new commissioner, he doesn’t receive much of a welcome from the indigenous people, and the distance of language and culture doesn’t leave much of an opening for him to gain ground in relationships. Only two women there, community leaders, make an effort to connect with him.

The island has a destructive colonial history, though, that haunts the people there. It revolves around the efforts by British Navy officer Captain J. Netherton to transform the island into a British outpost that would serve as the gateway to the Arctic. The story of what happened unfolds through the hazy Inuit legends of events that resulted in disappearances and deaths on both sides of the conflict. A century later and Fleet is replacing a commissioner who mysteriously disappeared, echoing the Netherton story.

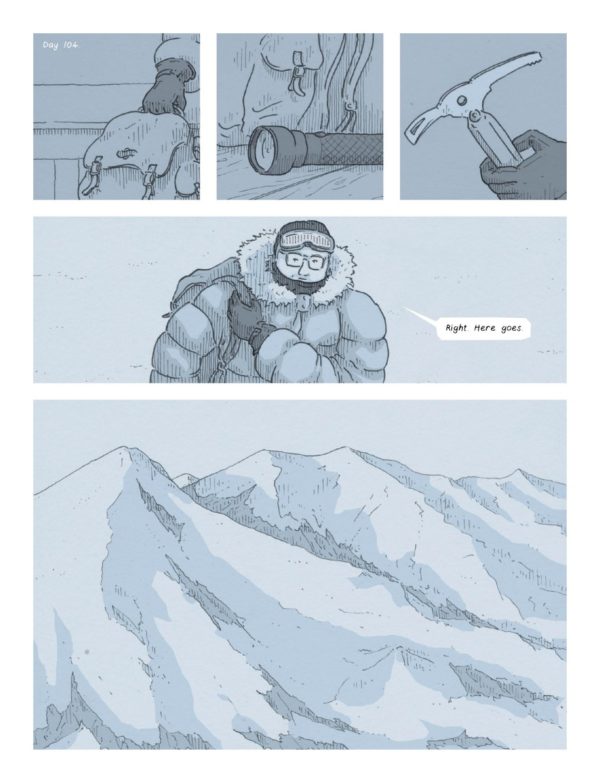

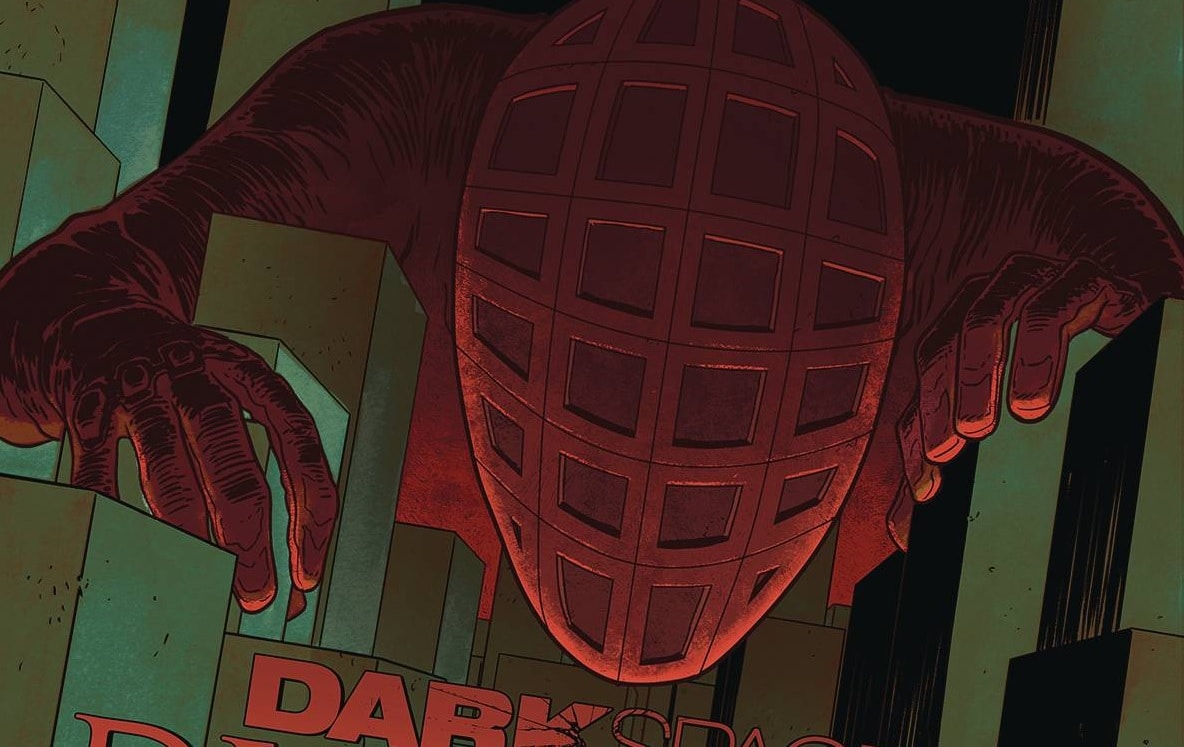

Fleet makes an effort to discover the fate of his predecessor as well as figure out what actually happened when Netherton arrived on the island. He sees these as his job, but is met with escalating hostility from the community as mysterious figures follow him and keep watch on him, and he finds mutilated animals on his doorstep. And to make matters worse, it’s the doorstep of a house that was built by Netherton to serve as the center of his new British outpost and has functioned as a home for commissioners since. Inside it’s a tomb of sorts and Fleet feels smothered by the atmosphere that its history creates.

In British Ice Pomery manages to pack a lot of background into this story without overcoming it with text, and also successfully transferring the implications of all the pieces to a wider critique about colonialism and the ongoing effects of it even as the citizens of the former empires have long since moved on from the immediate realities of it. He also manages to depict the alienness of the native culture in context of a British visitor without exoticizing it, thus turning it around to the responsibility of the visitor’s inability to pierce the barriers. Pomery also gives the story a stark mood with his artwork, offering a foreboding on the landscape as if the events of a century before have loitered there like an unsettling mist that won’t go away — much like colonialism itself.

But as I said in the beginning, British Ice does not shy from investigating the wounds that the historical burden has inflicted on the indigenous people inhabiting the island as Fleet arrives. It’s a consuming burden and a self-destructive one, and Pomery is able to present it as such without belittling the reason why it exists. That’s the double-edged sword of a fight for justice over generations — it can become a defining aspect of a community even as it’s unavoidable and even noble. As past and present are revealed to be not separate things but an ever-evolving continuum, the solutions become complicated and yet, as British Ice advocates, also entirely simple on the part of those in power if they decide to do the right thing.