While George A. Romero will forever be known as the father of the modern zombie, he did make a less popular but equally important contribution to horror cinema: a “vampire” movie called Martin (1978). I add quotation marks to the word “vampire” because this psychological horror movie does not conform to traditional definitions of the classic creature. Instead, it takes the route of social commentary to produce a young man who thinks he’s a vampire while being well aware of the power trip that is killing and then consuming the victim’s blood.

I was often reminded of Martin as I read Romero’s and Alex Maleev & Dalibor Talajić’s intelligently restrained zombie/vampire epic Empire of the Dead. In classic Romero fashion, political metaphors drive the story and multilayered monster characters, all of which are reflections of our own tendencies toward self-destruction within capitalist systems, reminding us that humanity has the capacity to change or perish.

A passing glance at the famed horror director’s body of work and it’ll be heavily apparent that capitalism is usually the ugliest and most discriminating of forces in his stories. The same applies to Empire of the Dead.

In Empire, New York finds a way to put up a wall between the undead and the few who are left alive. As is the case in almost all post-apocalyptic fiction, the remaining cluster of humanity finds a way to separate themselves into groups identified by socioeconomic class. The wrinkle here lies in the positions each monster holds (and humans are most definitely monsters in Romero’s zombie worlds) in the bigger picture.

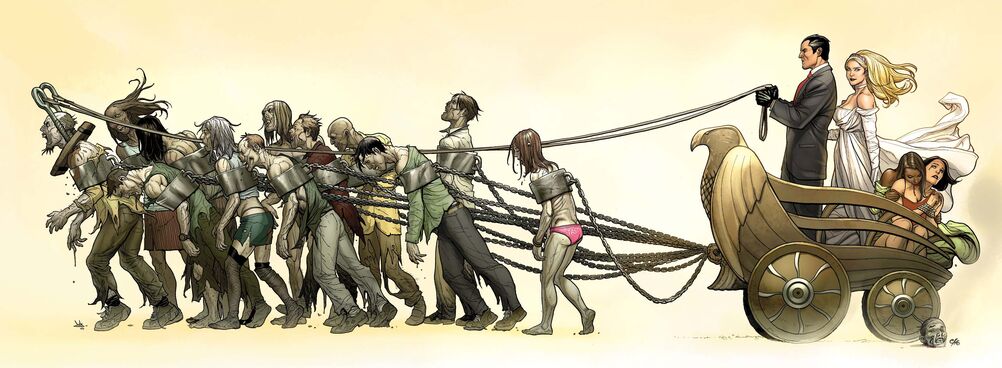

Zombies, in Empire, occupy the non-people caste, things humans can play with or enslave for mass entertainment. They are basically beings stripped of all rights. Humans, on the other hand, make up most of the middle-class stratum. They tend to be regular workers that keep the small piece of land currently operating in Manhattan from fully collapsing. Some of the more privileged among the living join the vampires in the upper class, a select group so distant from everyone else that rumors of their vampiric nature are kept unconfirmed.

The comic explores the dynamics of this hierarchical state of affairs by focusing on a zombie behavioralist called Dr. Penny Jones and a close human confidant to the vampire leader called Paul Barnum as they navigate the politics of what’s left of New York City.

Penny Jones is revealed to be the sister of Barbara Blair, the female lead of Night of the Living Dead (1968). She decides to confide in Barnum that her sister is the reason why she studies zombie behavior. Fans of the first film of Romero’s trilogy will remember that Barbara’s brother, Johnny, returns from the dead and grabs his sister as the zombie’s close in on the film’s leads in the final act. We assume she gets eaten, but the comic shows Johnny actually saved her. This confirms the idea zombies carry parts of their living personalities with them, an idea Romero first dives into in Day of the Dead (1985) with fan favorite zombie Bub.

That zombies can be trained or taught to behave so as not to see humans as a buffet of flesh props them up as victims of a system that had already conditioned them in life to consume endlessly. This is where the vampires come in to stir up Romero’s zombie metaphor. They are a biologically and intellectually superior version of the undead that can decide to satiate their blood diet more responsibly. Problem is, they don’t.

This is what happens in Martin. The desire for blood turns the titular “vampire” dependent on it, transforming him into a serial killer. The constant need to consume human life brings him closer in identity to the zombie, both stuck in a consumerist cycle of violence.

The contrast between these two monsters is philosophically intriguing as the vampires’ need for blood manifests itself more insidiously than the zombies’ hunger for flesh as a means of survival. It’s as if the American Dream were a race to secure the only reliable food source in an already depleted world. Humans, then, are presented as the cattle zombies and vampires depend on to further their existence.

The class struggle between these classic monsters finds a lot of inspiration in Romero’s own Land of the Dead (2005), in which zombies look to the last standing human settlement as the source of their post-life problems. Without vampires, Land turns to upper class as the proverbial bloodsuckers keeping the less fortunate among the living in poverty.

In both Land and Empire, the American Dream or the ideal way of life, lies in the more secure and privileged spaces inhabited by the higher class. Be it vampire or human, the metaphor works the same: power corrupts, oppresses, and disrupts the idea of human survival. Consequently, in both cases as well, zombies are the reminder that people still have the power to unite and overthrow. Bloody violence becomes the language that the mass of working people collectively decide to speak when they rise up.

And yet, it all depends on what’s on the line. Taking over a mall might not be too revolutionary, but overthrowing elitist vampires that want to take complete control over the remaining food sources seems like reason enough to unite.

George Romero is the master of political horror and Empire of the Dead stands as one of his most aggressively combative stories yet. It’s an unique addition to his zombie universe and it demands nothing less than his Dead films do: an insatiable hunger for change.