It’s a scary time to be a woman in America. Arizona recently decided to enforce a Civil War-era ban on abortions, the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, and the country’s legal machinery has been weaponized to control personal decisions regarding health and birth for the sake of politics. The United States is giving The Handmaid’s Tale a run for its money in terms of terror, and it’s winning.

As the fight for reproductive rights heats up even more (it’s been at high temperature for years now), two recent horror movies have decided to offer a fair amount of darkness to confront the social fears surrounding the loss of control women have experienced over their bodies: Immaculate and The First Omen.

The approach is religion and its capacity to misinform the populace on morality to the point of eroding freedom of choice. It’s all done under the guise of order and salvation, but the methods are chockfull of sin and spiritual corruption. In both movies, a pregnant woman must decide whether what’s growing inside her should be carried to term or be destroyed to prevent terrible things from happening. Nothing starts a conversation better than the coming of the antichrist.

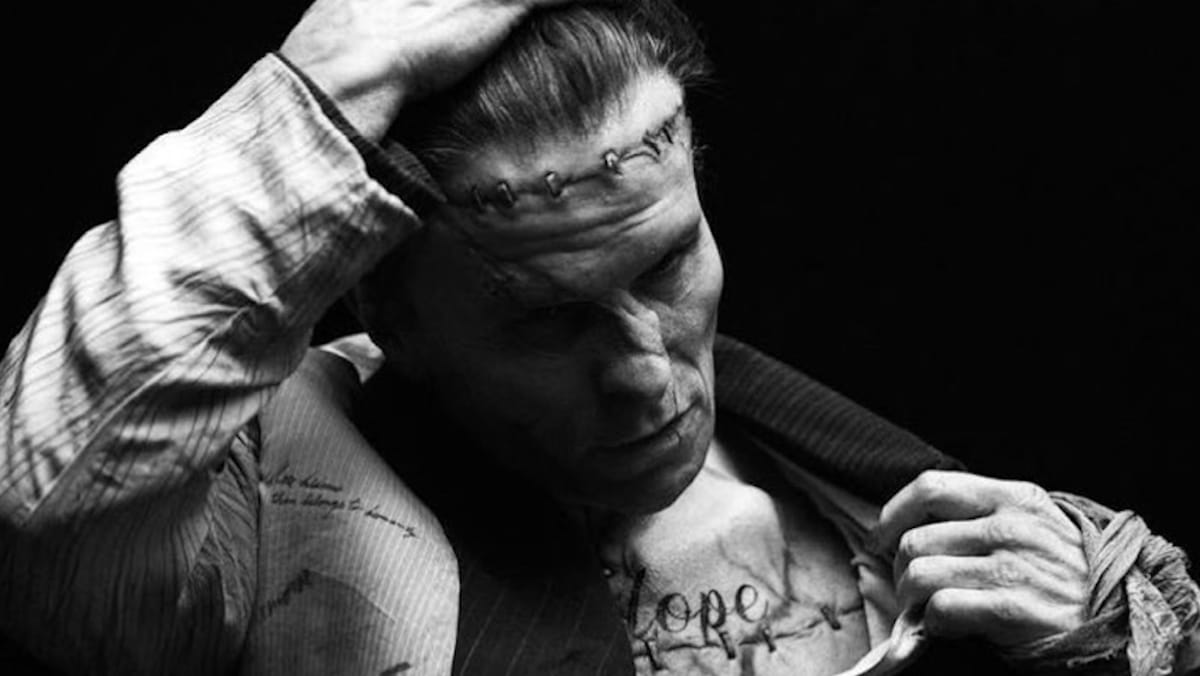

This is the route The First Omen takes, a prequel to the 1976 Richard Donner classic The Omen. Directed by Arkasha Stevenson, the story follows a young American novitiate called Margaret (played by Nell Tiger Free) that travels to Rome to lead a life of service in an orphanage run by the Church. Shortly after arriving, she uncovers a conspiracy that deals in demonic pregnancies and secret agendas from within the religious institutions she’s supposed to trust.

By virtue of being a prequel, the iconic Damien’s birth is a foregone conclusion. Where the story veers into reproductive territory is in the weight given to the arrival of the antichrist and how crucial it is that it isn’t interrupted or terminated. The orphanage the movie largely takes place in acts as a constant reminder of obedience and fanatic devotion to scripture, as if the fate of Christian faith depended on the delivery of every single baby. Deviation from it would put the Church at risk of fading far into the recesses of society, thus weakening its influence. Reproductive rights are seen here as an affront to Christianity.

Protecting life, the sanctity of it and the creation of future devout churchgoers, is all. The birth of new life to secure the survival of the Church, regardless of whether it entails bringing the antichrist into the world, supersedes every argument against it. There’s no room for compromise in this, which means the Devil will have it easy getting his kid to infiltrate humanity and bring about its demise. Control over women’s bodies is how this gets secured.

Michael Mohan’s Immaculate wades in the same waters, but it is more confrontational with the message. Blunt, even. Key differences in horror sensibilities account for this, especially in terms of health care for pregnant women from within the Church. In the film, an American nun called Cecilia (played by Sydney Sweeney) relocates to a convent in the Italian countryside to live a life of service. She gets pregnant shortly after arriving, but it’s revealed that it’s of the virginal variety. Cecilia is hailed as a new Virgin Mary, a vessel for the second coming of the Messiah.

The convent decides to take over her care entirely, even when they seem ignorant or ill-equipped to do so responsibly. A priest and a secret order of nuns keeps Cecilia confined to the convent, taking over her care and her body. The child is the priority, not the mother’s safety. If the pregnancy threatens her life, then so be it.

Immaculate comes across as the anti-Rosemary Baby (1968), a movie in which a woman is impregnated by the Devil and is then forced to give birth to the antichrist. In a 1969 review of the film for the LA Times, legendary writer Ray Bradbury expressed his dissatisfaction with that film’s ending, especially with Rosemary’s decision to cradle the demonic baby rather than steal it and sprint to the nearest church to ask God to get rid of it. Immaculate would’ve made Bradbury a happier camper.

Because of its bluntness, Mohan’s movie feels more urgent and more aggressive. Cecilia resists the convent’s attempt to control her more explicitly, and she’s given more agency in trying to regain control of her body. Whereas Rosemary’s Baby is more about paranoia and the hidden forces that impose domesticity on women, Immaculate prefers to look at how certain ideas are used to justify taking over the birthing process and how religion in particular uses faith to coerce women to fall in line with anti-abortionist thought. Again, it’s all about safeguarding the pregnancy at all costs, even if it means unleashing a biblical monstrosity upon us.

Abortion and reproductive rights have been steadily growing in presence within horror. Movies like Huesera and Antibirth are questioning outdated and conservative attitudes we still parade around regarding pregnancy and the unfair expectations we put on mothers-to-be, favoring attempts at understanding the decision some make not to become parents during or after the gestation period. John Carpenter himself threw his hat in the ring with 2006’s Pro-life, about a violent Christian fanatic that storms an abortion clinic just as his daughter attempts to get rid of a baby she knows was fathered by the Devil. Horror loves a good fight, and reproductive rights might be one of its biggest yet. The potential to scare some sense into people is just too good an opportunity to pass up.