The Beat’s Gregory Paul Silber has been accused of having a bit of an… obsessive personality. Each week in Silber Linings, he takes a humorous look at the weirdest, funniest, and most obscure bits of comics and pop culture that he can’t get out of his head.

This year, the dark comedy-drama film Poor Things won four of the 11 Academy Awards that it was nominated for, including a second Best Actress win for Emma Stone. Directed by Yorgos Lanthimos from a script by Tony McNamara adapting the 1992 book of the same name by Alisdair Gray, Poor Things tells the Frankenstein-like story of Bella Baxter (Stone), a reanimated corpse brought back to life by a “mad” yet kindhearted scientist (Willem Dafoe), as she joins a foppish lawyer (Mark Ruffalo) on an eye-opening, sexually-charged fish-out-of-water adventure through Victorian Europe.

It’s a great film and I highly recommend it (even more than actual Best Picture winner Oppenheimer), but it’s hardly the only film to riff on Frankenstein as of late. Over the course of the past year, there have been at least three other movies that are obviously heavily inspired by Frankenstein: the 2023 horror films Birth/Rebirth and An Angry Black Girl and Her Monster, and most recently, the 2024 teen romcom Lisa Frankenstein.

At least two more are in the works. One is the long-gestating Frankenstein film written and directed by Guillermo del Toro and starring Oscar Isaac and Jacob Elordi as Victor Frankenstein and The Monster, respectively. The other is The Bride!, a remake of 1935’s Bride of Frankenstein directed by actress Maggie Gyllenhaal with a cast that includes her old The Dark Knight co-star Christian Bale as the male monster.

Hell, even indie rock stalwarts The National (some readers may know them best for their Taylor Swift collaborations) titled their first of their two 2023 albums First Two Pages of Frankenstein (Laugh Track is the other one). As a fan of the band I enjoyed the album, but I couldn’t catch any direct Frankenstein references. Regardless, it’s clear that something is going on in the zeitgeist that’s got everyone thinking about mad scientists and reconstructed corpses again. What’s happening?

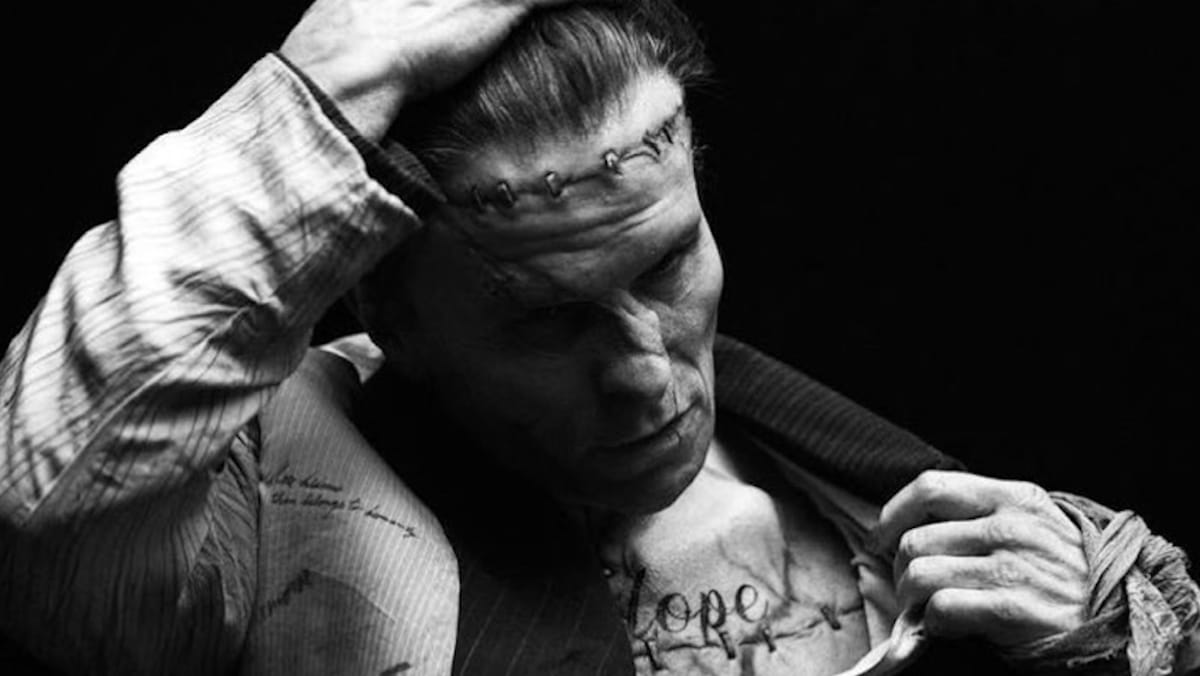

To investigate this phenomenon, I went straight to the source and read the first two pages of Frankenstein myself for the first time… as well as the other 214 pages. For good measure, and since they’re still so essential to modern Frankenstein iconography, I also treated myself to a first-time viewing of 1931’s classic Frankenstein and 1935’s even-better sequel, Bride of Frankenstein, both directed by James Whale and starring the legendary Boris Karloff as Frankenstein’s monster.

Let’s talk about the book first. I am utterly awestruck by what Mary Shelley was able to achieve with this novel when she was barely even 20. Her prose is beautiful, the story is suspenseful and thought-provoking, and Shelley invented multiple genres in the process. Shelley’s style may appear long-winded for contemporary tastes (she sure loved her semicolons) but it’s still quite accessible for a 200+ year old book. And unlike something like Moby Dick, Frankenstein was a hit in its own time, and was adapted into a stage play just a few years after the novel’s publication.

Contemporary readers, however, may be surprised by how different the book is from the popular image of “Frankenstein” that’s permeated throughout culture for the past century, which is mostly informed by the 1930s films. Yes, yes, most of us know by now that “Frankenstein” is meant to refer to Dr. Victor Frankenstein (for whatever reason his first name is “Henry” in the Whale films), not the monster he created who, at least in the book, never gets a real name. Said book is mostly told from Dr. Frankenstein’s perspective, and he only interacts with the “fiend” a handful of times.

The monster still looms large throughout most of the story though, as Dr. Frankenstein is haunted by fear of what evil destruction his creation is capable of… fears that ultimately become realized. By the end of the book, the monster has killed almost everyone Frankenstein cares about.

Yet the book version of the creature is even more of a “misunderstood monster” than the film version, even if he’s still very much the novel’s antagonist. I still love the grunting, moaning beast that Karloff played in the classic Universal movies, but in the book, the monster speaks in complete, eloquent sentences, even narrating a good chunk of the novel after a harrowing encounter with his creator.

One of the most interesting developments in the book, at least for me as a first-time reader, is that the idea of the “Bride of Frankenstein” is very much present in it, even if she never materializes into an actual character. You see, the first time Victor Frankenstein encounters the monster after his escape from the scientist’s laboratory, the monster demands that Victor make him a “companion” in the same manner he created the original monster. He desires a “bride” because the doctor unwittingly gave him a pitiful existence—everyone the “fiend” encounters, other than a kindly blind man, is so horrified by him that they often attack him. Out of fear that another monster could cause even more violence than the original, Victor continuously refuses to create such a creature again, even after the original monster kills the scientist’s entire family as vengeance.

That leads me to one theory as to why Frankenstein is back in the zeitgeist: as many have reported, loneliness is on the rise. There are a number of factors credited with causing this phenomenon, including, as you could probably guess, our increasing reliance on smartphones and other technology. Whatever the case, many of us are lacking the companionship we crave, whether it be romantic partners or simply platonic friendships.

Despite taking place in the late 1980s, borrowing from Frankenstein as a metaphor for loneliness is something that Lisa Frankenstein leans into. Written by Diablo Cody (the film apparently takes place in the same universe as Cody’s previous cult-classic horror comedy, Jennifer’s Body), and directed by Zelda Williams (daughter of the late, great Robin Williams) in her feature debut, Lisa Frankenstein tells the story of Lisa (Kathryn Newton), a teenager in a new high school struggling to fit in following her mother’s death at the hands of an axe murderer. She becomes enamored with the grave of a long-dead young Victorian man (Cole Sprouse) and revives him, gradually rebuilding more of his body over the course of the film with a staggering amount of violence for a PG-13 film. In any event, the “Frankenstein” of this film eventually becomes Lisa’s love interest. It makes for an absorbing, if tonally unusual, romantic comedy.

There are all kinds of things we can point to as causes for the loneliness epidemic, but I’d wager that the pink elephant in the room here is that we’re still reeling from the COVID-19 pandemic. I’m sure I don’t need to tell you that the isolation we experienced (hopefully) trying to curb the spread of the Coronavirus took a toll on our mental health. Frankenstein’s monster was isolated too.

Of course, the bigger problem with the pandemic wasn’t loneliness, but death. Death is nothing new to the human experience, of course, but between the deadly pandemic, mass shootings, climate disasters, and multiple ongoing genocides around the world, death has loomed over our lives for the past few years more than recent memory. Many people lost friends and family members, and when you lose someone close to you, it’s natural to wish you can bring them back.

Frankenstein riffs explore that fantasy, even when they’re cautionary tales about the dangers of trying to play God. An Angry Black Girl and Her Monster, directed by Bomani J. Story, follows teenage genius Vicaria (Laya DeLeon Hayes) as she tries to revive her brother following his murder, while Birth/Rebirth follows a mother, Celie (Judy Reyes) and a scientist, Rose (Marin Ireland) as they go to violent lengths to reanimate Celie’s dead daughter. Both films explore the extreme lengths people go to in an effort to fight grief, even at the expense of others.

Yet when you’re thinking so much about death, you can’t help but also think about what it means to be alive. Dr. Frankenstein gave his monster a “life” in the sense that he can communicate and move about the world at his own free will, but what kind of a “life” was he given if he can’t sustain relationships with anyone? In that way, I would argue that one of the themes of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is that our lives are largely defined by our ability to interact with others.

This is something that Poor Things explores beautifully, because it, too, is ultimately a film about what it means to be human. Bella Baxter is brought to life as a fully grown adult woman, but she’s “born” with the brain of a small child—yet her brain develops rapidly over the course of the film. Much of the film follows Bella as she learns to navigate Victorian social mores, questioning the “rules” that many take for granted. For example, when Duncan (Ruffalo) scolds her for spitting out her food, Bella replies “why should I swallow it if it’s repulsive to me?”

As the world started to open up more from the (still ongoing!) pandemic in 2021, I think many of us found ourselves struggling to learn how to interact with others again. Living in a crowded city like New York, I noticed many strange behaviors during this time, like a man being kicked out of the Apple Store in downtown Brooklyn for screaming at the employees. Sure, whacky people are nothing new for NYC, but something about this period felt different, like we were all learning how to be human again.

That, ultimately, may be why Frankenstein is on so many of our minds recently. I think we’ve all felt like Frankenstein’s monster at various times in our lives, but especially in the last few years. We’re lonely, misunderstood, sad, and confused. Maybe by making us think about what it means to be human, Frankenstein stories help us feel less alone.