As far as Muslim representation among superheroes goes, Kamala Khan a.k.a Ms. Marvel has been one of the most successful in a thin field. The first Muslim superhero seems to be Kismet, who appeared in 1944 in Bomber Comics, created by the pseudonymous “Omar Tahan,” and then Kismet disappeared seemingly forever. That is until Boston-based comics writer A. David Lewis decided to bring the character into the 21st Century.

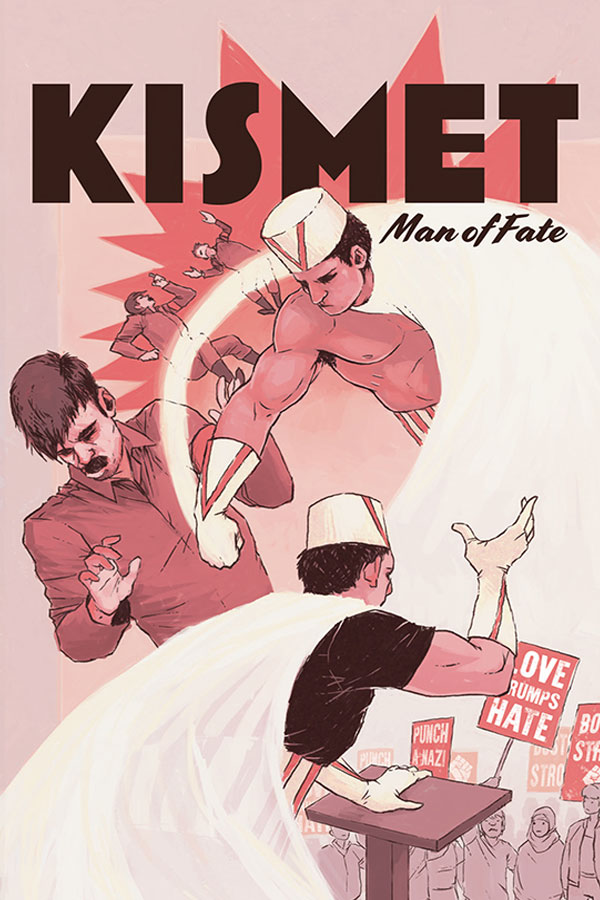

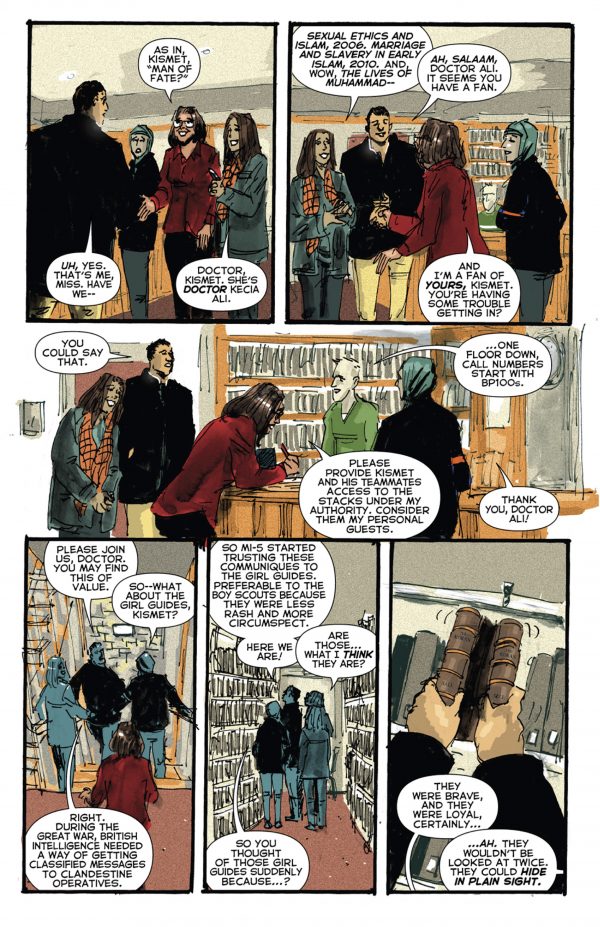

Kismet returns to comics with the publication of Kismet, Man of Fate, written by Lewis, with art by Noel Tuazon and Rob Crooneborghs, letters by Taylor Esposito, and cover by Natasha Alterici, published by A Wave Blue World.

Lewis, who has written comics like the Harvey-nominated The Lone and Level Sands, has also studied and written about the intersection of religion and comics in scholarly works like American Comics, Literary Theory, and Religion: The Superhero Afterlife, which began life as his Ph.D. dissertation.

——————–

How did you first become aware of Kismet?

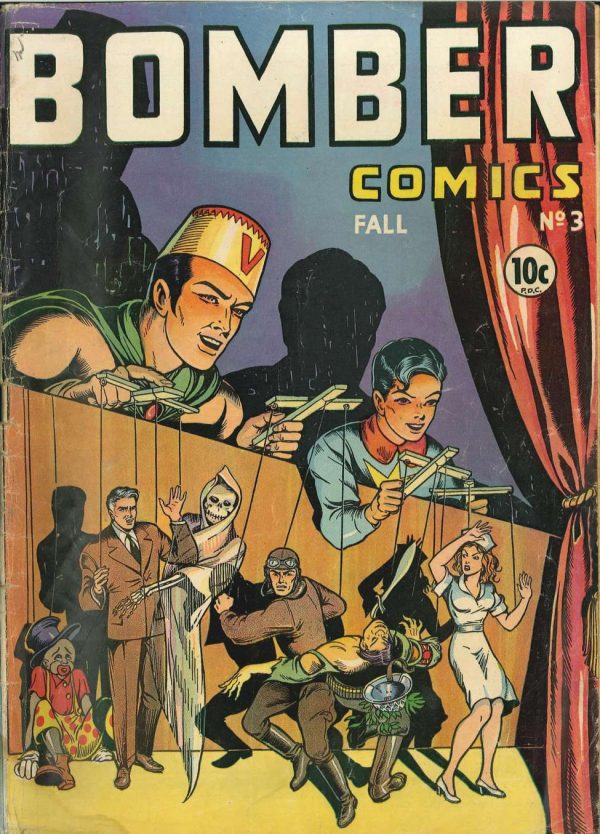

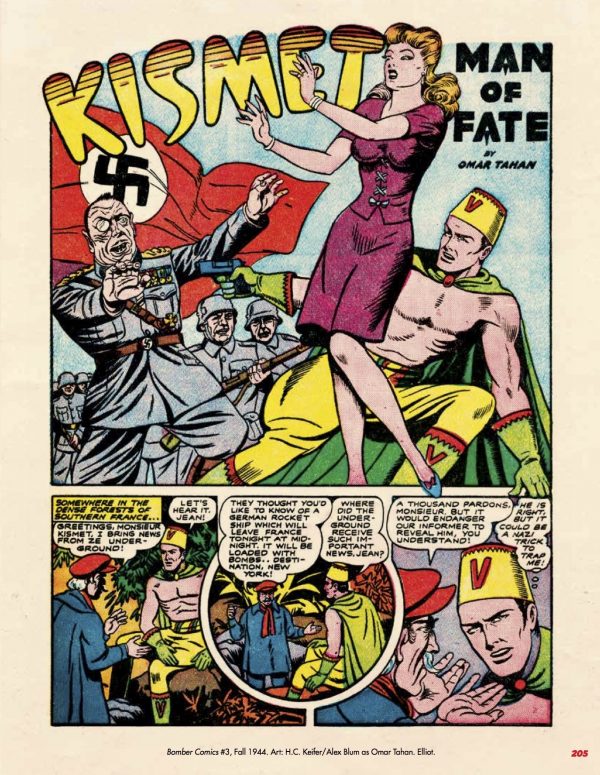

My introduction to Kismet came through academic research. I was actually doing some work on looking at depictions of Muslims in popular culture and then comics specifically and then even more specifically in the superhero genre. And I discovered that in 1944, there was a Muslim superhero that ran through four issues of Bomber Comics created by the S.M. Iger studio, the same one that Will Eisner co-ran previously. So I was fascinated to learn this, and I probed back further, and I found depictions of Arab or Muslim supervillains and such, there wasn’t much before 1944. So I locked in on this character as really the first one. And the thing that was most surprising wasn’t how far back this was, but how charming it was.

I was bracing for something to be horribly stereotyped or, they didn’t have the term at the time, but Islamophobic, but instead Kismet was written with this charm and nobility and panache that really won me over, made me want to learn more about the character even outside of my research. And there wasn’t anything! He fell into the public domain, and his fate was doomed when Elliot Publishing became Gilberton Publishing. I think I have that right. Later when Gilberton was acquired, mostly for its Classics Illustrated catalog, the rest of its comics, including Bomber Comics were left to the public domain. So Kismet would’ve just been an interesting, funny little footnote in history. I wanted more, and the only way I could get more was to make more. Fortunately, in addition to the comic studies, I wasn’t an absolute stranger to making comics. I had done a few graphic novels and worked on some anthologies, so I have the tools at my disposal and artistic collaborators available to do just that.

What aspects of the original stories appealed to you that you wanted to keep this new version? Was there anything you wanted to dispense of?

The thing I wanted to dispense, but instead I had to negotiate with, was the costume. This was a bare-chested, caped, fez-wearing Algerian fighting for free France in World War Two. I mean, his costume was totally outlandish, but that gave me a hook in a way. The only reason that someone would wear something so ridiculous, especially in a wartime theater was if they had to, and if they had to put in real trust that their abilities exceeded their appearance. Right? So the first thing that I wanted to bring to the story was the idea of Kismet’s — I don’t want to say confidence or optimism — but his absolute sense that things would work out, that things were the way they were supposed to be and that ties into the idea of Kismet itself and to the idea of fate and even the Quranic idea of predestination or determinism.

Basically, Kismet wore the costume because he had to trust that his abilities, that has powers, that his skills would make up for being a moving target, being the most garish, outlandish thing there. I liked that he was confident. I’d liked that he was written as intelligent. He was not written as having some weird pidgin, outsider English accent. It looked as though, and this was not a great concern for the Golden Age writers, he was fluent in German as much as French, as much as Arabic, as much as English. So I’d like to the idea that he was a polyglot, that he knew many tongues. And finally, they kept it short of him being roguish. There’s no chauvinism or overt sexuality, but he is a little swashbuckling at the same time. And I loved that, and I love that in a number of characters. And I was thinking whether there were ways to maintain that without it becoming a farce.

You do address some of the outdated aspects, like his appearance, in a way that acknowledges it but also translates it to a modern sensibility in a gentle way.

I like to think so. I mean, I hope it accomplishes that at the very least, I don’t leave it as a blind spot — well, I got a guy running down the street with a fez, and a cape and no one would blink an eye. Instead, I try to negotiate it. And I think there’s something about superhero fiction in general, comics fiction more largely, that you have to give the audience credit. If you at least raise a topic, acknowledge a topic, then they will be very forgiving. My philosophy is if you acknowledge that you know this is outlandish, you know this is far fetched, even the character sees it as far-fetched, so long as they can negotiate it, then their suspension of disbelief can be maintained rather easily if things that are omitted or skipped over or left as blind spots that might become a difficult part of the story to swallow.

In the original story, did they exhibit much fluency in either Islam or the Algerian situation or was it more an affectation for a superhero story?

It was much more an affectation. And this was the era where comics were grabbing from folklore and from cultures on a very super official level, but all around the world. I will say at the same time it was nice that they didn’t try to push a particular image of Islam because I think that could have been even more disastrous in the hands of what I’m assuming were white New York … it may have been men and women. Research has shown that Ruth Roach was working there at the time and she may have had a hand in writing this, so sensitivity to an outsider status may have been sort of baked in if she was writing in what was largely a boys club. But no, Islam was neither featured nor explored. It was more an excuse by which they could give this character amazing adventures.

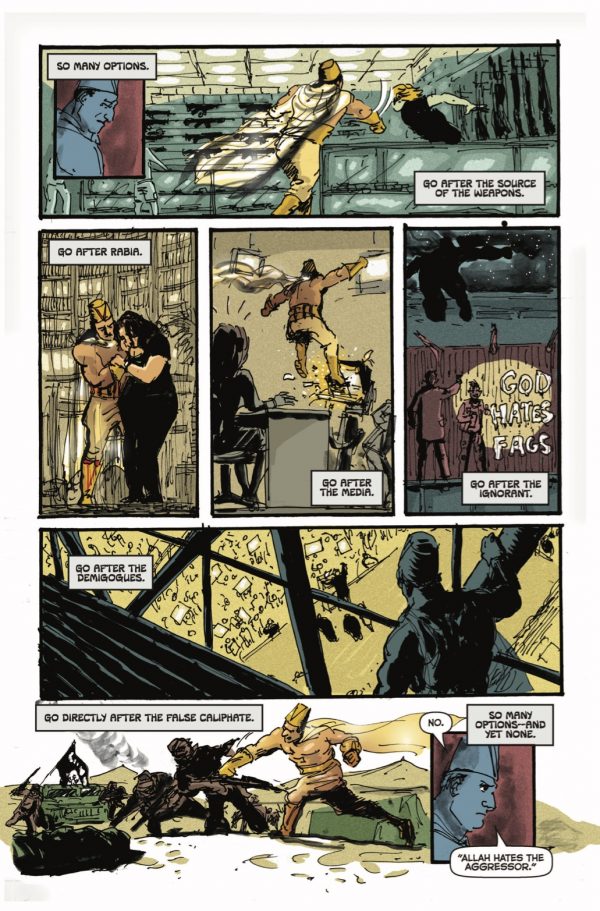

As you update it, you embrace politics pretty strongly, and in some ways, it reads like part examination and part reaction to the Trump phenomenon. It takes place during the election, and that is very much a part of the dialogue that goes on.

Yes, and that itself is kismet. That’s serendipity. That is to say when I was first researching Kismet just for academic purposes, and then even thought of creating new stories from, Trump was not a phenomenon yet. The rise in Islamophobia was, certainly. A growing divide in American sensibilities was, certainly but Trump hadn’t come center stage yet. By the time A Wave Blue World and I decided to do this long form and not just do short stories or put it in an anthology. But yes Donald Trump and his campaign and then his administration were a huge cultural force that everyone was dealing with, but that I particularly was struggling with.

I think it would have been disingenuous for me to try to bring a Muslim character, a Muslim superhero character, to the present and have him be entirely disconnected from the political and cultural climate. I definitely turned into the skid which made the story very much about that. Again going back to my earlier point to acknowledge that this has to be part of the current story. I surprised myself with how much it became part of the story, but it became very natural. It is dovetailed for me as a creator, and I think for my collaborators. It dovetailed really easily. When the A plot, the surface narrative is about power, responsibility, all that great superhero stuff, how can you not discuss issues of justice, of law, of patriotism, and rip it right out of the headlines?

In the last year, there were headlines proclaiming Boston as America’s most racist city. Since Kismet takes place in Boston, how did that enter into your storytelling?

Finally, we’re getting to the place of write what you know, right? I don’t know what it’s like to be Algerian. I’ve had to do a great deal of research there and talk to different people. Um, I’ve only myself been Muslims since 2012, so I did not grow up in the faith. And I’m not a superhero obviously. But Boston is something I knew and could speak to, and it’s absolutely true. Boston has a troubling racist history, there’s no getting around that. What I’d like to take hold of, however, is the opposite side of that coin. Either how Boston has changed or what conflict there has been or what evolution there has been. It felt like the right city to do this in, and fortunately, I’m here. I’m not only that, but I could relate both the good and the bad that was going on during the Trump campaign and the early days of the administration, the protests, the Alt-Right demonstrations. But you’re absolutely right. Boston does not come off smelling like a rose. I can’t help but still love the city, but I have to love it for its challenges as well.

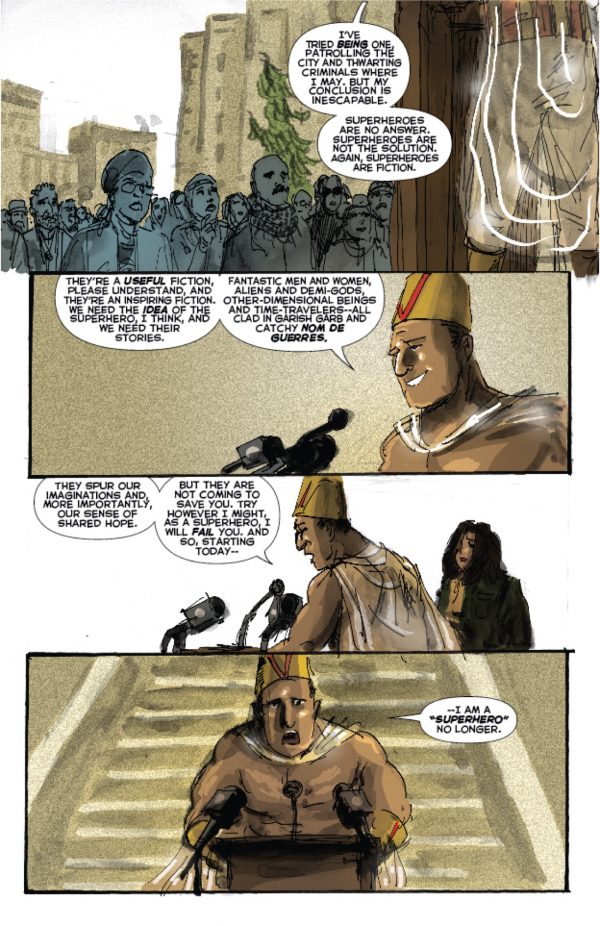

In the story, you have the character transition from superhero to activist, and there’s a great scene where he makes a rallying call telling people not to wait for someone else to save them, that they have to do the work themselves. You bring in the real world with that point and also question the idea of super-heroics, which made me wonder if Batman would be more effective as an activist.

There’s that joke that Bruce Wayne should have funneled all his money into the Gotham welfare system instead of creating a Bat Cave.

Crime fighting sure is a treadmill superheroes get stuck on. You catch the criminals, you lock them away, they escape, you do it all again. Activism is more about trying to solve the problem.

I think I put these exact words in Kismet’s mouth, that superheroes are a useful fiction in that they’re inspiring, right? And they’re reassuring. I love stories of superheroes. I am not anti-superhero, but the problem is that superheroes are really well designed for the comic book medium. They’re really well designed for television and for movies. They are not well designed for real life. And to have them in our entertainment is great and I welcome it, and I love it, and I am a consumer of it, but they are a poor model as to what one can do in their own life. And I got Kismet to walk right on that line. Here’s someone who is in the comics medium — he doesn’t know that. And in the superhero genre — he doesn’t know that. But he does have this realization that this is not a real-life solution. That hook, early on in just the process of rediscovering Kismet and thinking about what I wanted to do with him, was really what got me excited. It was what gave me the most — I’m going to use a fancy word — raison d’etre.

That’s the big fancy academic way of saying, well, why on earth should I do this? What’s the point? The reason to be was that I could use this character to address how superheroes are useful and then how they’re not.

What kind of future does Kismet have?

I very much want to write more, and we’re talking with the publisher right now about how and when to schedule that. So there’s a very promising future ahead for Kismet. There are basically two directions to go in, and I’m going to try to do it simultaneously, which is always fun and challenging. There’s a lot of backstory that I still have sketched out but didn’t want to jam into this first volume, from where his superpowers derive, to what was his exiting reality for 70 years all about, to what brought him back now, et cetera, et cetera. But there’s also the rest of the Trump administration to deal with and the history that we’re living day to day. I have set up a few things in the first volume that will actually tie the character even more closely to things happening in Washington D.C.

He’s not leaving Boston, but he’ll have affairs, and that might take him to Washington D.C where I lived and where I have a number of friends in politics. So again, I can still write a bit of a what I know. If there’s one other thing I want to do with the series, it’s explore the other characters. I’m really proud that Kismet is not the only representation of Islam in the book that we have different shades of Muslim characters in the book interacting with each other. And I like to go further with each of them into their own lives. So there is a lot of exciting potential for Kismet if people continue to want it. And so far the reception’s been very positive.

A. David Lewis is not only a scholar of comics, but also a pretty darn good guy. He edited my GN Dracula vs King Arthur and spent time doing research to help make our dialogue pop with a more medieval tone. I credit him with helping us turn what could have been a big silly mess (pitting two public domain characters against each other) into a more grounded in mythology tale. His own solo work is well-crafted and worthy of your attention. Happy to see him receiving recognition and will definitely buy a copy of Kismet. I hope you decide to as well.

Comments are closed.