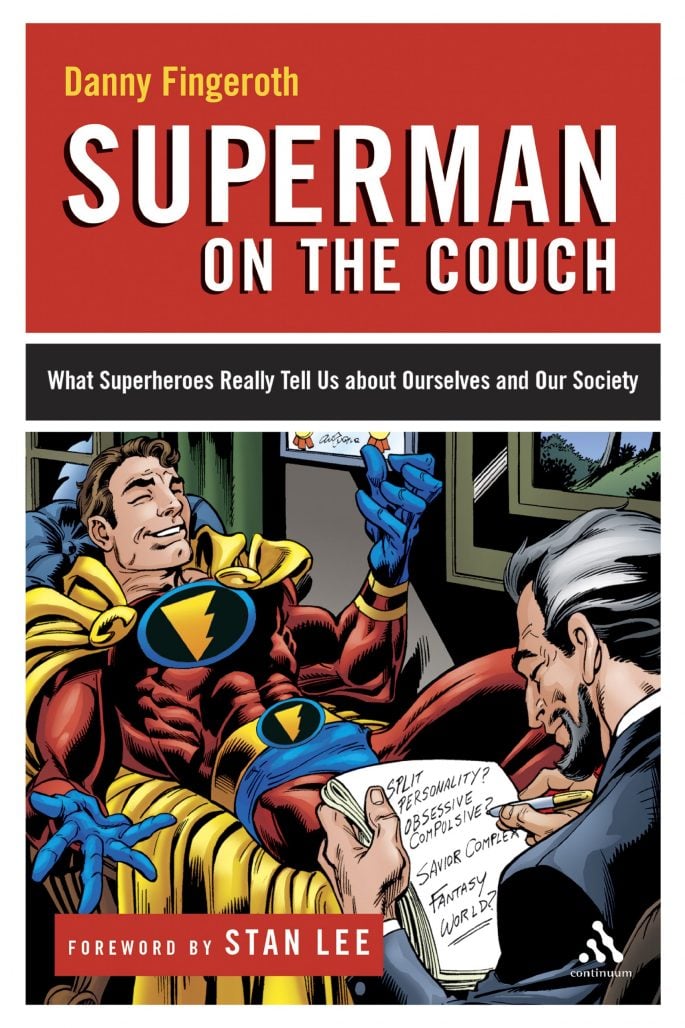

Danny Fingeroth, in his own words, has worn a lot of hats. To a generation of Marvel fans, he may be best known for his lengthy tenure as the editor of the Spider-Man family of titles, as well as the writer of comics like Darkhawk and Dazzler. He’s also had a rich career as a nonfiction prose writer, among other things, in the decades since his 1995 exit from Marvel as a full-time employee, with books like Superman On The Couch: What Superheroes Really Tell Us About Ourselves and Society, and Disguised as Clark Kent: Jews, Comics, and the Creation of the Superhero.

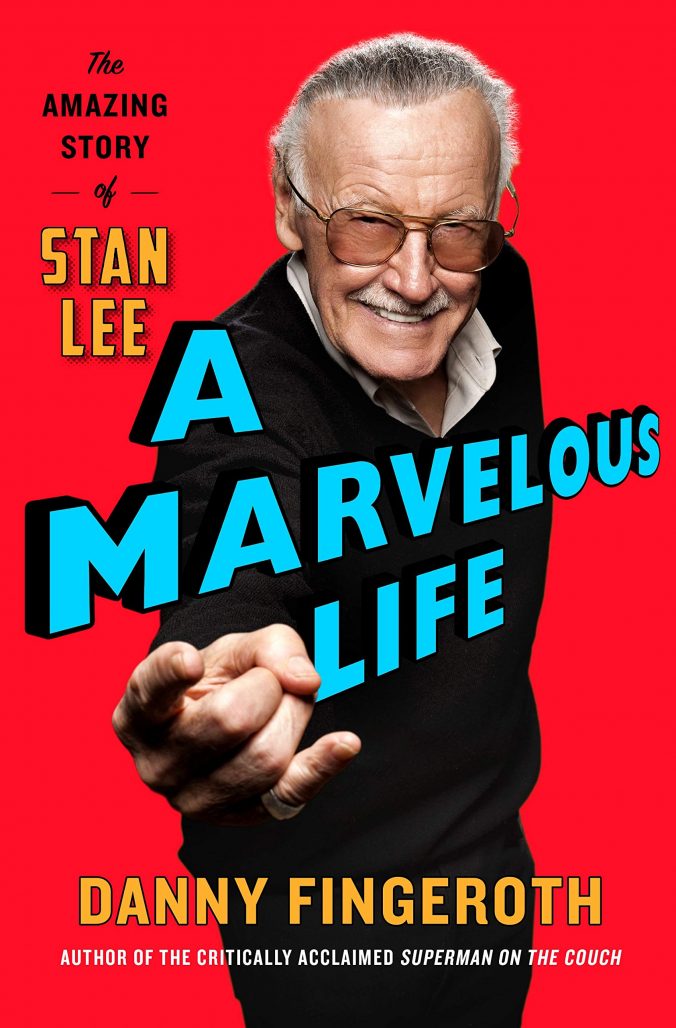

I’d been interested in Fingeroth’s work since meeting him at the 2018 Jewish Comic Con in Brooklyn, where he led impassioned panels on seminal Jewish comics creators like Will Eisner and Jack Kirby. But following my two-part interview with fellow Stan Lee biographer Abraham Riesman about his heavily-publicized True Believer: The Rise and Fall of Stan Lee, Fingeroth reached out to me to offer his own perspective on Stan “The Man.” After all, despite what several outlets erroneously reported, Fingeroth, not Riesman, penned the first Lee biography to come out after the Marvel figurehead’s death, in the form of A Marvelous Life: The Amazing Story of Stan Lee.

I got on the phone with Fingeroth for an in-depth chat about his eclectic career, his relationship with Lee, Stan’s difficult-to-define relationship with Judaism, and much more.

Gregory Paul Silber: I figured a good place to start would be if we could talk about your transition from being a comics writer/editor to, you know, doing what you’ve been doing now for, as far as I can tell, the last few decades, being a… is academic the right word for it?

Danny Fingeroth: Academic, historian, critic… I’ve been wearing a lot of different hats. I can see why you would say academic, but I think that’s a little narrow… and yet “expert” seems a little broad. I generally say, “pop culture critic and historian.” It really depends on who’s asking!

Maybe we should start by discussing how this interview even came about in the first place, because in a way that ties in to my life and career journeys, and your interest in discussing them, which is much appreciated.

So let me start by saying that the way this came about was I had seen your interview with Abraham Riesman about his recent Stan Lee biography. And somewhere in the interview it was said– I have a feeling this came from the public relations department of his publisher – that his was the first biography of Stan Lee to come out since his death. I found that odd because not only did mine come out first, but mine also came out from a large publisher, Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin’s Press/Macmillan. And they had put on a big publicity push that sent me out on a book tour all over the country. It was everything you would hope that a big publisher like that would do. So I was kind of surprised that multiple media outlets would take the other publisher’s publicity statement at face value. This turned up in a New Yorker magazine article, too, that his was the first book about Stan from a major publisher since his death in 2018. This is no judgement on Abraham’s book. Just me wanting to get timelines straight.

So (A), I found that a little troubling, and (B), I put into play a lesson I learned from Stan Lee: Don’t be shy. I immediately contacted anybody who seemed unaware of my book and said “I’d like to clarify that mine came out first. If you’d like a review copy of my book, let me know. And if you’d like to interview me about it, also let me know.” And you were kind enough to take me up on my offer.

Anyway, now that that’s out of the way, let me try to answer your question about how I got to where I am as some kind of academic or expert or whatever.

Comics will break your heart, you know? Much like baseball, much like life itself. So I was part of a generation that came to Marvel Comics in the mid and late 70s, most of us college-educated and most of us with families who probably would prefer we do something else [laughs]. But we all ended up at Marvel in various ways. Many of us like me, were native New Yorkers. Others were from out of town. We worked in comics as editors, writers, artists. The history of comics has taught us that with the exception perhaps of Stan Lee and one or two other people, very few people have a career in comics that lasts more than 20 years, certainly not as a staff member for a single company. And yet a bunch of us had done just that for 15 or 20 years.

If you are a Marvel editor, especially in a high profile one like I was on Spider-Man – I was the group editor on Spider-Man, and with the other editors in the group, I’d been putting out, like 15 to 20 different Spider-Man related titles a month – you get to the point where you’re thinking “I’ve been here for close to 20 years. I beat the system.” Earning money like a lawyer, but I didn’t have to go to law school. And you get to feel pretty good. And then you’re a boss of a department. You have a staff. You keep getting good raises. People keep saying what a great job you’re doing. Your books are selling, your boss loves your work. And you go “Wow, I bet I can do this for the rest of my working life. That’ll be pretty cool!”

And then reality intrudes, and suddenly you realize that this high-pressure but enjoyable place you’ve been working for is really owned by a corporation. They’re not concerned with your personal fulfillment. They have no sentimental attachment to the fact that you’re getting to work on Spider-Man, whom you loved as a child, or The Avengers whom you loved as a child. Many of us had the veil lifted when Marvel went through various unnecessary—in many of our eyes—upheavals in the mid-‘90s. You go through your life and career thinking “Editor-in-Chief of Marvel Comics, that’s something to aspire to. That’s a high-level job that affects the whole medium and so many people’s lives and careers, and so many characters…”

And then push comes to shove in some kind of corporate, economic, real world scenario and you go “Oh, Editor-in-Chief of Marvel Comics is kind of middle management. There’s a half-dozen levels above that person. And I need to pay attention to that kind of thing, not just to my direct boss.” So what happened was that Marvel went through a so-called “Marvelution.” I think there were some very ill-considered decisions made at the upper corporate levels by people who thought they were selling soap or potato chips or I don’t know what. They didn’t get how to handle entertainment and entertainment franchises and the people who make them. So that was all that nonsense that led to an unnecessary bankruptcy in the late ‘90s. Along the way, and virtually overnight, from my point of view – you know, hindsight is always 20/20 – suddenly, working at Marvel… with a whole staff working for me with crossover storyline sales in the millions and weathering the crisis of the Image Comics guys leaving Marvel and starting their own company… I came in one day and reality had shifted. On paper, everything was the same, but there was a corporate restructuring. Everything changed, and not in a good way.

Reality shifted overnight. It’s become almost like a comedy trope: “Friends became enemies and enemies became friends.” Alliances were made and broken. Kind of crazy. I realized for numerous reasons that I needed to get out of there. A lot of people ended up being laid off. I was not one of them. I was continually getting large bonuses to make me stay! But my day-to-day life was very unpleasant. I started looking to get out, and publisher Byron Preiss offered me a job running a line of Internet comics that was so early it was called “Virtual Comics.”

Silber: Oh, wow.

Fingeroth: And so I left Marvel in ’95. That was a tough decision. After nearly 20 years in a place, you think, “Maybe I’m one of those rare people who get that fiftieth anniversary gold watch and a testimonial dinner or something.” But that was not to be the case. So that sort of started this odyssey for me. I worked for a couple of years doing Virtual Comics, where we invented a lot of things that are now standard in digital comics. You know, initial problem-solving, like “How do you translate a comics page to a computer screen?”

I brought over a lot of writers and artists and editors from Marvel to work with me. That was an Internet startup and it was a joint venture with AOL when AOL and their greenhouse were big. But eventually our funding ran out and we got to the classic – maybe you’re a little too young, but anybody who’s worked in the early internet who is reading this will find it familiar – the company you’re working for would say, “We can’t pay you anymore, but if you keep coming in, you can use our computers, printers, and fax machines to look for new jobs. Come in and make it look like we’re still in business—we’d really appreciate it.”

We were a little bit ahead of the curve because our comics essentially required the ability to download large files, and most people in the mid-‘90s weren’t able to do that. I later worked as SVP of Development for a company called Visionary Media. We were putting out short form flash-animated shows that we would then pitch to studios. We ran into the same kind of problems. In both cases we were a little bit ahead of our time and got caught up in the undertow of the crash of the early 2000s internet.

So I had these various skills, including writing and editing, and other things I discovered I could do, like teaching, lecturing, putting together interesting panels and events, writing books, writing criticism. It was an interesting adventure to, like many of my peers, find yourself in your 40s and to have all this knowledge and experience, but who do you sell it to? You know, the people running the comics companies, understandably, like we did, wanted new people, or they wanted their own friends, people they’d worked with or were comfortable with.

Anyway, one thing I did was, I wrote a book called Superman on the Couch: What Superheroes Really Tell Us About Ourselves and Our Society.

Silber: Yep. I’ve got that right in front of me.

Fingeroth: I also wrote Disguised as Clark Kent: Jews, Comics, and the Creation of the Superhero, both of those for superstar editor Evander Lomke at Continuum, who I’d gone to high school with. And for Penguin, I wrote The Rough Guide to Graphic Novels. I’ve taught at NYU and the New School and at art schools, and I’ve lectured in England and Italy. One thing I’m trying to do currently is to expand my reach to being someone who is a cultural and entertainment and media expert and critic and biographer, not only about comics, but to catapult from comics—which is now part of a mainstream culture—to more general cultural expertise. So right now, my agent is pitching around a couple of book ideas. One is a biography of Jack Ruby, the guy who killed Lee Harvey Oswald. You may have seen a version of Ruby in “The Umbrella Academy” last summer!

Silber: I actually have not watched that yet. I should. I’m a big Gerard Way fan from his music, but I have not watched the show yet.

Fingeroth: Well, the interesting thing is that Ruby is still a figure that people know even if they don’t know anything about him beyond the famous photo of him shooting Lee Harvey Oswald. I’ve also been pitching around with artist Rick Geary a graphic novel about Ruby’s life. The book is a book and is different because from the GN because it goes more into depth. Both tie into my interest in quirky Jewish Americans. Jack Ruby is a very strange Jewish-American story. I had access to Jack’s rabbi, who shared with me his 50-year-old notes from when he visited Jack in prison, which he did regularly.

I’m also a big Bob Dylan fan. I’m considered—by me, anyway—one of the leading authorities on Bob Dylan in relation to comic books. Again, certainly a quirky Jewish American.

Silber: Yeah, no kidding.

Fingeroth: So I have a Dylan book proposal circulating (not about Dylan and comics, though). There are hundreds, if not thousands of books about Dylan. Nonetheless, I think my take is somewhat unique. So those are things that I’ve got out in the world, and of course the Stan Lee biography was and is a major thing for me. I don’t think anyone else has written one from a comics industry insider perspective.

That was a very long answer to your question!

Silber: Since you left off on Stan, let’s continue with that. You mentioned a little earlier that unfortunate but true truism from Jack Kirby that comics will break your heart. Something I often think about is that the counterpoint to that is… yes, we all know about the history of labor abuses and things like that, but there’s really nobody in comics who didn’t get into it because they sincerely love comics. Because let’s face it, if you are only in it for the money, there are easier ways to go about that. I assume that you came into comics having started out at some point in your life as a fan. Am I correct there?

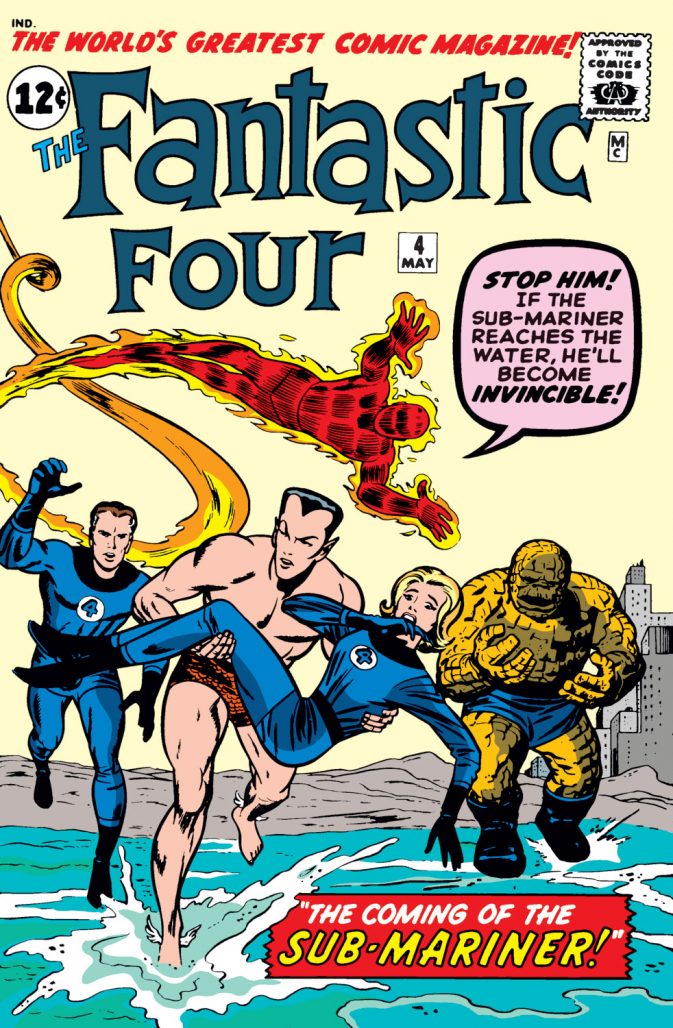

Fingeroth: Yes, but not a capital-F Fan. I was not somebody who was going to conventions or joining fan clubs. But let me just jump back a second to the way you phrased something. Yes, it’s largely true that nobody from the ‘70s on got into comics as not-a-fan. In my particular case, I was a fan as a kid. I was the perfect age for the very first Marvels. I’d been reading comics for several years already and was a little jaded without realizing it. And suddenly… Fantastic Four #4! That was the first Marvel I read. The interesting thing is, you know, Marvels were out there, but they didn’t have any branding. They had that tiny M.C. on the cover, which—according to Roy Thomas—nobody actually knows for sure whether or not that stood for Marvel Comics. It could have been some other notification for the distributor or something else.

Silber: Heh, it could be any number of things. They’d used the name Marvel off and on since the 40s, as I have no doubt you know.

Fingeroth: Yup. I was the perfect age for that voice of Stan Lee on the covers and the words in the stories and in the letters pages and the bullpen bulletins. The stories were great, and the work of Kirby and [Steve] Ditko and [Larry] Lieber, all that stuff was just perfect for me. But I would say my initial fan enthusiasm lasted more or less until Kirby left for DC. It’s hard to parse out how much of that was the comics running out of that initial steam, and how much of it was just me getting older and developing interests in underground comics and movies and literature. Around that period I kind of transitioned from superheroes to being very interested in the Will Eisner comics that Jim Warren and then Denis Kitchen was publishing, and in undergrounds, and especially in the work of Harvey Pekar in American Splendor. I did follow Kirby’s work at DC, too. The Fourth World stuff.

In college, I was a film student at Binghamton University, but comics were always in my radar. After graduation, I came back home like kids will, which for me was New York City. And, kind of like Stan Lee, I thought it might be interesting to work at a comic book company for a while. I was able to arrange an informational tour, and that led to me getting an entry level job as Larry Lieber‘s assistant. Larry had come back to Marvel after a brief time away running Atlas Comics, which is a whole other comic history saga.

I was hired to be his assistant in a department that was mostly putting out reprint material for the British weekly comics market. Working in comics seemed like a good fit—like film, it was working with words and images—and it seemed like it could be more than just something to do for a few months. I thought, “All right, this is a creative field, but there’s a regular paycheck and benefits. That’s pretty good.” It wasn’t a huge check, but there was the opportunity to make more freelancing, moonlighting for the same company. And the people there were interesting. And in addition, here were my idols from childhood in and out the door—Frank Giacoia, Mike Esposito, for examples, and John Romita Sr. and George Roussos on staff—telling stories about comics’ past and about other folks who were legendary names.

So it was interesting in that sense, and interesting in the sense that it was writing and art—creative stuff. And yet, it was also a business—albeit a business that seemed like it was on its last legs. It felt like we were sort of in the last stages of this kind of quaint American folk art. It was dwindling and, you know, “Last one out, please remember to turn the lights off.” You wouldn’t know then that it would regenerate itself and then end up generating all these media extensions now, billion-dollar movies. Nobody was able to really imagine it quite at that level.

Anyway I worked my way from the British department into the mainstream comics where I ended up—to make this really brief—Group Editor of the Spider-Man line, writer of Darkhawk, etc. I’ve just telescoped a lot of time into a short summary. And we haven’t even discussed the Clone Saga…

Silber: I was going to ask you this, but you pretty much answered this through the other stuff you said: you got into comics at least partially during that period where Stan and Jack and people like Steve Ditko, in the 60s, were firing on all cylinders… I don’t know if you mentioned this in your answer to my previous questions, but I do know from other times we’ve spoken, you did have a face-to-face relationship with Stan Lee, is that correct?

Fingeroth: I worked with Stan in various capacities over many decades. Oddly enough, I worked with him more when I left Marvel than when I was at Marvel. I did a magazine for Two Morrows publishing called Write Now magazine. And out of that came a book, The Stan Lee Universe, that Roy Thomas and I did about 10 years ago. I’d been Stan’s editor on a few Spider-Man stories over the years, which is kind of a surreal experience. But he’d already moved to the West Coast by then, so I’d say maybe every couple of years there’d be some project where I’d work with him.

Then when I went to work for Byron Preiss—Byron was actually pretty close with Stan—Stan did a number of projects with us, including a series of prose novels that were branded Stan Lee’s Riftworld. They were about an imaginary comics publisher, loosely based on Stan. Stan and Byron brainstormed them along with the guy who actually wrote them, Bill McKay. We also did a comics adaptation of Riftworld. We had Dan Jurgens doing some of the art. This was in the mid and late ‘90s. Stan was involved in the plotting and was doing the scripting. I was his editor on that. And then I interviewed him a number of times for my Write Now magazine. And I did convention panels with him when he and I were both on the Wizard World circuit. So I developed a sort of email, phone call [relationship].

But I never considered myself to be in his inner circle. I had a friendly, collegial relationship with him. He certainly would always take my calls and emails. He knew me as a as a familiar voice and face from over the years. I also did things with him when I was at Visionary Media, which was that online animation company. We did some things with him at Stan Lee Media before the shit hit the fan with that company. We were doing a crossover venture with them.

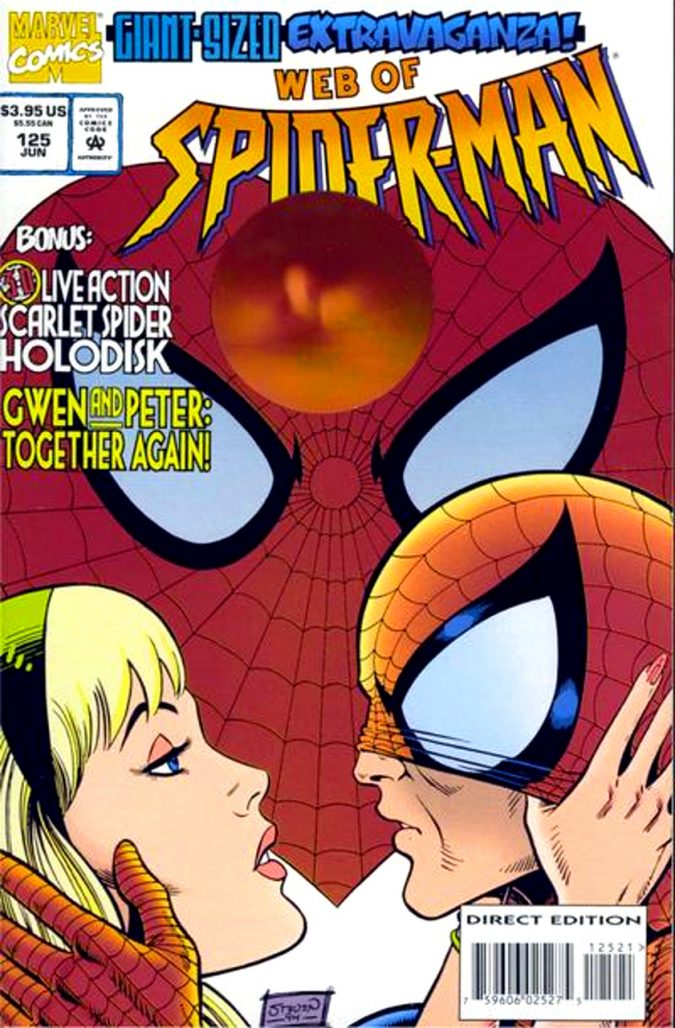

Probably the most interesting thing was…in early 1995 when I knew I was leaving Marvel. I allowed myself to be sent on a business trip to California, where—if you remember the Marvel holodiscs from the Spider-Man comics in that period…

Silber: I don’t think I was reading comics at that time.

Fingeroth: I saw it mostly as a chance to go to the West Coast and network and get the hell out of Marvel at that point. But for those discs, we were using, literally 1920s technology to make 3-D Spider-Man and Scarlet Spider moving images that you needed a special penlight to look at. I directed a gifted actor named Scott Leva, who pretty much incarnated Peter/Spidey in that era, in those discs. Those were fun to do. Most people, though, didn’t have such a light. If you did, it was great effect…

Anyway, that was a time when Stan felt that he was being marginalized by the company. Marvel was starting to have financial issues, the boom of the early ‘90s was starting to slow down. This was right around the time that he did that long cameo in Kevin Smith‘s Mallrats, so he had that beard. I was out there and I had dinner with him and [Lee’s wife] Joan, and you could feel that Stan was feeling ill-treated. He felt like he still had a lot to offer, and a lot of energy, and yet nobody running the company seemed to know what to do with him. He had this line of comics he was doing for Marvel, the Excelsior line, that nobody seemed to really be very supportive of. So we kind of bonded a little over the fact that we both felt we were being marginalized by this place that we had devoted our entire careers to.

Stan always let you sneak a peek behind the facade a little bit. He couldn’t help it. He really wanted people—perhaps subconsciously—to see behind that facade, but that seemed to me like a time that he and Joan really opened up to me to some degree. Then, at the San Diego Comic Con that that same year, when Stan was doing that project for Byron, he and Joan would come sit at the Byron Preiss table—I had just left Marvel and started there–and I got the sense that they’d been through it before.

On the one hand, somebody buys Marvel Comics and you’d think they would say, “Well, we’ve got Stan Lee, let’s pay him a lot.” But, really, what a lot of the new owners each time would say is, “What are we paying this guy so much for?” [Laughs] Or they would veer back and forth between extremes in how they treated him. Joan was bragging about the fact that when there was a problem, that’s when she would bring in the lawyers, to protect Stan’s interests. This is well before Disney bought the company.

That was sort of eye opening for me because… if Marvel could treat somebody like Stan Lee as someone who was an expense they don’t want to bother with, where does that leave people like me? [Laughs]. Anyway, as I said, I wouldn’t say I was his best buddy by any means, but I developed a friendly relationship with him. And I think that was useful to me in writing the biography. Most people who’ve read it think it’s not a hagiography, even though it’s definitely a more positive than negative look. But I think I lay out both the positive and negative aspects of his career and accomplishments. And I kind of let people take those facts and make their own decision about what he did and didn’t do. That’s what I tried to do, anyway.

Silber: It does sound like you were in an interesting position to write a Stan Lee biography because you did kind of walk that line where he certainly wasn’t a stranger to you, and you did know him personally, but because you weren’t quite in that inner circle, like you said, it’s not like you’re writing about your best friend. I think with any biography that someone writes– and this goes for you, this goes for Abraham Riesman, this for anyone writing about anyone else– there is always that question of what is the relationship between biographer and their subject. I understand that your book came out after Stan had died. But you had started the process of writing it long before that, correct?

Fingeroth: Right.

Silber: I’m really curious what kind of interactions you had with Stan while that process was going on.

Fingeroth: What I bring to the table when writing about comics, and about Stan in particular, is an understanding that, since I was an editor and a group editor and a writer at Marvel Comics… I won’t ever say I have the same job as Stan. Obviously I didn’t. But there were enough similarities in the jobs that I had to ones that he had at various times that I could put myself in the mindset to imagine what he was up against and what he had to deal with at various phases when he was editing comics. And I could do that in a way that even the most skilled journalist or historian couldn’t have, because they didn’t have that analogous experience to go on.

So the process of the book… as every author does, I had to really decide, “Okay, I’ve written these books… where do I go from here with my subject matter, with my interests, you know? Where do my interests coincide with a book that large numbers of people might actually want to buy?” [Laughs] Books that will sell to more than a highly motivated group of fans and/or historians. I mean, I’m happy to sell to people interested in history and academics, and I count myself among them. But how do I sell something commercial? Oh, a book about Stan Lee. And so I’d been working on that. I’ve been advised by some people in publishing that it’s better to have an authorized biography. I don’t know if that’s true, but I tried to get Stan. I had a couple of meetings with him and his people about doing an authorized biography and ultimately he said to me, [Fingeroth does a great Stan impression] “Danny, if I wanted to do, it would be with you. But I don’t want to do it.”

[Laughs]

Was I the tenth person he said that to that week? I don’t know. [Laughs] But I said, “Alright, maybe once or twice a year I’m still going to nag you about it, because you were naive enough to give me your email and your phone number. So I’m going to, you know, just try to get you to do it.” And he never did. But he said, “You know, look, I can’t stop you. If you really intend to do this, do an unauthorized biography.” So that’s when my agent started pitching that around. So it’s an unauthorized biography. No one besides my publisher had any approval rights.

In retrospect, I think in a way it’s unfortunate that the title of my book is “A Marvelous Life: The Amazing Story of Stan Lee.” When people hear that title, they think it is just going to be an authorized, in-house hagiography. I knew we had to somehow get the word “Marvel” in the title one way or another, and that was how we did it. It’s funny, I was just reading a review that came out last year on a website somewhere that said about one chapter of the book something like, “I’m surprised that Disney let this chapter go through.” And I’m thinking, “Are you such a moron that you think this is a Disney book?” [Laughs] It’s not a Disney book. It’s not a Marvel book. It’s not authorized in any way, shape or form. It’s been carefully proofread and vetted by the publisher’s editors and lawyers. But it is an unauthorized biography.

When I made the deal for the book with St. Martin’s Press, I did call Stan to tell him, “Hey, remember that book we talked about, the unauthorized one? Well, guess what? I got a contract!” [Laughs]. And he said to me, “Well, good luck with it. I’m not going to tell people to talk to you or not to talk to you. But I don’t want to be interviewed. I’ve been interviewed too much.” However, whether it was my adorable, obsessive, nagging manner, or maybe just because he forgot that he said he wouldn’t do it, I did two lengthy interviews with him for the biography, in the spring of 2017, about a year or so before he died. And he was very frank in them. I won’t say it’s his last interview because he did live another year or more. But I think the interviews, of which I excerpted large parts in the book, were some of the last lengthy, in-depth interviews he did, and some of the last interviews he did with someone who knew his life and understood what his job and his career was about in a way that somebody not from comics wouldn’t.

The editor who bought the proposal went to another company before I turned in the manuscript, and I think the people who inherited it at first weren’t paying that much attention to it, until at a certain point, especially when it seemed like Stan was about to die, I definitely got a “Hurry up with that Stan Lee book.” I think maybe even some of the people who were overseeing it at the publishing company also thought, “Oh, this is going to be a puff piece.” And then they got this in-depth, analytical, and, I think, highly entertaining book. I did my best to make it a cliffhanger and a page turner. But the thing has over 300 endnotes. I did my homework and cited my sources. I made it clear when I was speaking as me and I tried to give ample voice to Kirby and Ditko and everyone else. Besides Stan, I interviewed around 50 people. Neal Adams, Mark Evanier, Dennis O’Neil. I did lengthy interviews with Stan’s brother, Larry Lieber, who was my first boss at Marvel!

So I think that, you know, the title may lead people to think, “Oh, this is just a pal of Stan’s writing a purely complimentary book.” And while it’s clear that I admired Stan, I also tried to spell out the ways that some things he did were not so wonderful or idealistic. It’s funny, “A Marvelous Life” seemed like an appropriate title, and it gets all information across: This is a book about Stan’s amazing life, and much of what he’s known for and what he did involved Marvel. But nobody at Marvel, nobody in Stan’s camp, nobody had any approval other than me and my editor and publisher. There’s nobody’s agenda that the book is fulfilling.

Silber: You bring up something that is really interesting and very frustrating for people like you and me and really anyone who is knowledgeable about this side of comics history, where the mainstream– and when I say mainstream, I mean, people who probably don’t read comics but could recognize Stan Lee whenever he shows up in a cameo in a Thor movie or whatever– where they see Stan Lee, and on one hand, you have the people who are like, “oh, Stan Lee, he created Marvel.” That’s frustrating in its own way, because of people like Jack Kirby and all that. But there’s also that side of it where you bring up all the people who are saying things like, I can’t believe Disney approved this,” as if Stan Lee was not his own whole person who existed outside of this company that he was associated with and he made a huge impact on. This idea that he kind of existed as a mascot rather than a person who can have a biography like anyone else, I think that’s a really interesting thing to think about.

So something I’d like to ask you, especially considering that you knew Stan personally as well of all the things that you wrote about him in his biography, what’s something really big that you feel like people don’t know, or rather don’t understand, about Stan Lee?

Fingeroth: Wow, there’s like half a dozen different answers to that. One thing, I think, is that you will often hear a grudging statement from people like, “Yeah, he was a terrific editor and a great promoter, but he wasn’t really a very good writer.” I think that’s bullshit. I think he was the perfect writer at the perfect time for those comics. Was a lot of the plotting done by a lot of the artists? I think it depends on the artist. Certainly if you’re talking about Kirby and Ditko, I think it’s pretty clear they often did most of the heavy lifting of the panel-to-panel plotting. But I think Stan gave each character, each story, gave the entire line a unique and powerful and memorable voice. As editor, art director, head writer—and relative of the publisher—he could do that. Did it make for great stories? Yes. Was it fair? That’s another question.

Could he have done it without Kirby and Ditko? Of course not. But could they have done it without Stan? Also no. So I think to damn him with faint praise and just say he was a great marketer and maybe an inspirational editor…but an untalented write… I think he really understood human nature. I think there was a part of him that was still that poor, desperate kid from Washington Heights that he never lost touch with, certainly not in those early Marvel stories.

So I think, Spider-Man’s guilt and self-doubt and bouts of depression and self-hatred, and the complex inner lives of the Thing and Captain America…I think that human stuff came from Stan taking the raw materials provided by Kirby and Ditko, as well as drawing on his own life, and putting that stuff in there. He loved to say, “I’m the ultimate hack. I don’t write anything if I’m not being paid. The minute I leave the chair, I forget about it.” I’m sure that was true at times. But I think he cared and gave more than he wanted to admit. Because to admit that would be to admit that– and look, this may not be surprising from the guy who wrote a book called Superman on the Couch– but I mean, I think there’s a reason Stan didn’t want to admit how emotionally wrapped up he would become in the stories, certainly while he was writing them. I think he was ambivalent about being in comics at all. He often said, “I wish I gone to Hollywood 25 years earlier, 20 years earlier.” But he didn’t. And I think it’s because he had a lot of self-doubt and he was in a kind of velvet-lined trap.

I think Stan brought an understanding to his best comics of a version of human emotion that would connect with readers in the ‘60s. And, I think, to this day, what virtually all the Marvel products traffic in is what Stan and Jack and Steve and Larry and the rest came up with in the ‘60s. People say, well, you know, that first 20 years of stuff—the stuff Stan was writing from ’41 to ’61—wasn’t so good. But the stuff was… certainly good enough for what he was writing, the Westerns and the romance and the comedy. But to say that those 10 years of those great ‘60s Marvel comics weren’t great writing from Stan says that humans can’t grow and develop, that whatever a person was between ages 17 and 37, it’s impossible for there to be growth and development and to rise to a creative challenge laid in front of him by his brilliant collaborators. I mean, I think that really does Stan, and if you’ll pardon my grandiosity, does humanity a disservice.

Look, Stan’s relationship to the truth is very interesting. I went to Stan’s archives in Wyoming and I listened to a lot of tapes of his talks and events. I like to say that Stan was a compulsive truth-teller. Because he would often say stuff that was very frank. Of course, sometimes he’d bend the truth or outright lie. That’s part of the package.

But you’d see him on a panel and it would be like, “boilerplate, boilerplate, mind blowing revelation, boilerplate, boilerplate.” But it was all said in that public Stan Lee voice. He would say some incredible things about himself personally, or about how he felt about an artist or something, in the same huckster tone of voice that he would tell you to go buy the next issue of Captain America. But if you listen or if you read transcripts, you often go, “Well, here’s a guy who’s frank in a way that is unexpected from somebody in that high in a position, and from anybody.” And then, he’ll follow it up with something that’s clearly not true. So, maybe that’s something else I bring to the table in writing about Stan, the ability to discern the boilerplate and the bullshit from the frank revelations.

Silber: The first time I met you was at Jewish Comic-Con 2018. Whatever the last time they did that was, like 2018. I talked to Abraham Riesman about this, and I’d love to ask for your perspective too on the Jewish aspects of Stan’s life. Especially since you wrote a whole separate book about Jews and superheroes. A lot’s been written about Stan’s personal relationship with Judaism. But something I’d really like to ask you: is there something about the Marvel superheroes that Stan co-created wrote that you did that you think is like particularly Jewish? Or perhaps even, particularly un-Jewish?

Fingeroth: Stan was pretty typical of a certain approach to Judaism in his generation. I think it’s still common. He was one of the children of Romanian, Jewish immigrants. I think his father was fairly religious. I’m not sure about his mother. I never get straight if they had a kosher home or not. I think they did, you know, but I’m not sure… there was certainly a certain amount of observance. I think his father was a regular synagogue attender. Stan seemed hell-bent on being all-American and assimilating. He had a Bar Mitzvah at his father’s insistence, which was very lightly attended at his synagogue in Washington Heights.

But I think he was culturally Jewish, you know? He loved Mel Brooks’ 2000-Year-Old Man, if you know those comedy routines, which are based on an adorable elderly, eastern European, immigrant Jewish man. If you look at Stan’s friends… they were largely Jewish. So I think he was Jewish culturally. I don’t think he had interest in the religion, or any religion, even if he did write an epic poem called, “God Woke.” I think he wanted to assimilate. His ideal woman who he ended up marrying was kind of the embodiment of Protestant, blond haired beauty.

But there’s a story that Jim Mooney tells. Stan used to walk a lot in Manhattan, both as exercise and a way to think, and to socialize. He loved walking. He was full of energy. One day Stan and Mooney, one of his closest friends – and an iconic artist himself, of course – were walking around Manhattan. Stan’s got a beautiful new suit on. Very proud of it, you know? And as they’re walking, a pigeon craps on Stan’s suit.. Stan is upset, although I think he and Jim both found it funny in a way, too. But as the pigeon is flying away, Stan waves a fist at the bird and shouts: “For the Gentiles, you sing!” I’m guessing he may have used the phrase goyim, not gentiles. But it’s a very funny line, and I think a very Jewish line.

So for all his good looks and well-tailored suits and toupees and, trappings of a successful suburban lifestyle, a pigeon could still crap on him and ruin his beautiful suit, and his go-to response to that was a kind of borscht-belt, Catskills Jewish humor.

When Stan wrote the foreword to my book Disguised as Clark Kent: Jews, Comics, and the Creation of the Superhero, I suggested to him that he might want to sign off instead of just “excelsior,” “excelsior and zei gezunt,” [Yiddish for, “stay well”] And he did. But in that foreword, you can see… conflicted feelings about being Jewish, that I don’t think he often spoke about.

Oddly enough, people always say that in the early Marvels, “Ohh, Spider-Man is Jewish, the Thing is Jewish.” But in researching and writing Disguised as Clark Kent, I stumbled onto this incredible Jewish metaphor by both him and Kirby in the story of Thor and Jane Foster, in Journey into Mystery, those early stories, and not just in one issue. Thor, Dr. Don Blake, wants to ask his nurse, Jane Foster, to marry him and reveal to her that he’s Thor. And Odin, who is drawn looking like a biblical Moses, forbids it. “No, you can’t intermarry with a mortal! A God cannot marry a mortal!” Even if you say Kirby brought it in, which we don’t know, certainly Stan could have said, “Jack, chill with the intermarriage theme, let’s do something else.”

But they milked it! They kept going with it. Finally Odin throws up his hands. “Fine! Bring her to Asgard. I’ll give her powers.” In other words, she’s going to convert to Judaism, metaphorically. So she goes to Asgard and Odin grants her powers. And it’s disastrous. She can’t control them. She destroys half the palace and she’s miserable. So Odin zaps her back to Earth and immediately arranges for Thor to meet Sif, a nice Asgardian girl down the block, a warrior goddess.

And I’m thinking, here you have Lee and Kirby. They’re both the children of immigrants. Stan’s solution to the conundrum of being Jewish in America was to marry a gentile woman and not raise their daughter Jewish. And that seems to have worked out. They were married for close to 70 years, until she died. Kirby takes the opposite approach. Kirby marries literally the Jewish girl next door, and they, too, were very happy. There’s no one path to a happy ending, but I found that Jane Foster storyline, in many ways, to be maybe the most Jewish expression in early Marvel.

In general, they would pepper their comics in the way that Mad magazine would do, they would throw in some Yiddish phrases like furshlugginer. A lot of what Marvel did was certainly imitating, to some degree, the EC Comics of the ‘50s including a sort of Yiddish sensibility that they managed to get in there without apparently alienating or confusing readers who were not Jewish or not from New York. Stan claimed to be an atheist, and that may well may well have been the case. But I think he certainly never lost contact with a certain kind of New York Jewishness.

Anyway, I’ve blabbed on more than you anticipated, I’m sure. So let’s save something for a sequel interview.

Silber: Sounds good. Thanks, Danny.

Fingeroth: Thank you, Gregory.

A Marvelous Life: The Amazing Story of Stan Lee is in stores now.