Abraham Riesman is the author of True Believer: The Rise and Fall of Stan Lee, a new biography of the iconic writer and editor available now from Penguin Random House.

In the first half of our interview, Riesman guided us through his exhaustive research process and shared his thoughts on the perennially controversial matter regarding Stan Lee and his claims of creating the Marvel universe.

In this second half of our interview, we conclude with a frank discussion of Stan’s Jewish heritage: his rejection of it, and readers’ attempts to find Jewish themes in the work of Stan Lee regardless.

Gregory Paul Silber: Pulling the curtain back for readers a little bit: our original plan way before COVID, way before the book got delayed, was to have a live chat at my family’s synagogue in New Jersey.

Abraham Riesman: Oh yeah. That’s right.

Silber: I think it was pretty implicit that we were going to mostly focus on the under-explored and under-discussed aspect of Stan’s Jewish identity, or as some might argue, lack thereof. So even though that obviously is no longer a feasible plan for a number of reasons, could we talk about that? Because I was really glad that you do get into his Jewishness.

Riesman: Yeah, that was a big priority for me. I mean, I’m Jewish and I’m very passionate about learning about Jewish history, especially Jewish-American history. The whole ecosystem of Jewishness is something that fascinates me and that I take very seriously. So when I started this book, I was like, “I’m going to do my best to excavate the Jewishness, or lack thereof, of Stan Lee.” And it was a really interesting process.

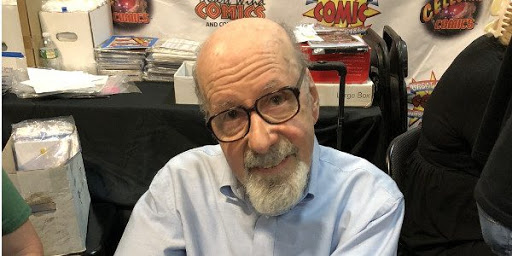

A huge window into it came through this very long, very generous interview I did with Larry Lieber, Stan’s brother. I opened the book with this. Just about 40-odd days after Stan died, I interviewed Larry at his apartment on the Upper East Side, where he’s lived since, I believe, 1968. It’s a studio apartment. He and I talked for about four hours. It was this unbelievably revealing and emotional interview, and featured the magic words that every journalist wants to hear, which was a number of times he said, “I’ve never told anyone this.” I really thank him deeply for taking the time to speak with me.

And that was the first window into the Jewish stuff, because Stan never really talked about being Jewish. When he did, it was always in sort of blasé “well, that’s not really who I am” ways. He told an interviewer once, like, “I don’t believe in religion, not just the Jewish religion, but all religion.” In his memoir, there’s a very weird passage where he talks about how he and his wife couldn’t adopt because “she was Episcopalian and my parents were Jewish.” Not ‘I’m Jewish.’ “My parents were Jewish.” So he didn’t really identify with the Jewish world, but he obviously had a Jewish background. Larry provided insight into that, and genealogical research provided a lot of insight into that. Now, a lot of that was just going through records that are online.

But also, I did hire a great genealogist whose name I’ll happily shout out, Meryl Schumaker. She has a company called We Go Way Back. Har har har. It’s a genealogical research company that she does. I hired her because I reached sort of a wall when it comes to my genealogical research in terms of databases I have access to and expertise that I have. So Meryl took the baton and ran with it and found some amazing stuff that helped me get perspective on the other things that I’d already learned. And ultimately I was able to get, not a complete portrait of Stan’s Jewishness, but I think the first real attempt at having an honest portrait.

There has been plenty of writing about the secret Jewish history of Lee or the Jewish side of Stan Lee, and it’s always thin analysis. You’ll have an example of a story and you’ll be like “this is like the legend of the Golem” or “this is this is like something from Pirkei Avot about where it says that you should be nice to people.”

Silber: [Laughs]

Riesman: All this stuff that’s not actually inherently Jewish, and people would then completely ignore the fact that he was never talking about being Jewish. He mentioned once that he became a bar mitzvah, but that he’d rushed it and he didn’t want to do it. His dad made him do it. But then once I started asking questions and doing the research, I found out that it was a very interesting, and in some ways, sad Jewish story. You have this dad and this mom who come from eastern Romania, where they fled horrific anti-Semitic persecution. The worst that was happening in the world as of when it happened in the late 19th century, and like the first few years of the 20th century. They escaped these horrific conditions. His dad lived through a pogrom when he was a few years old. They make it to the United States separately.

It all sounds somewhat familiar, right? Eastern European Jew comes to New York in the 20th century. But you realize once you start digging in, “oh, I actually don’t know those stories. I know the caricatures of the story. I don’t know any of the details about what it was like to be a specifically Romanian Jew. A specifically Romanian Jew in the Lower East Side. A specifically Romanian Jew in the Bronx, which is a completely different context. How observant were the families, what industries were the families in.”

All these things matter. It’s a fractal. You keep thinking, “Okay, well, I’ve got the contours of what the Eastern European Jewish immigrant experience was like.” But the more you zoom in, the more the contours loop around. You have to rediscover what you’re talking about. And it was fascinating. One of the things that’s very sad about it on some level, depending on how you think about Jewish continuity, is that Stan ended up being really the last Jew in that line. He abandoned Jewishness pretty explicitly. That’s not me accusing him of something. I mean, he never identified with Jewishness. He actively sort of rejected it.

Suffice it to say that Judaism has not lived on in his family. And you’ll see how that played out [in the book]. It’s interesting, for me at least, to think about a line that you can trace back so many millennia, and then sort of seeing that line end. For whatever reason. It’s beyond moral judgment. It’s just seeing the end of a Jewish story is kind of an interesting and emotional thing. And I hope I conveyed that interest into something interesting in the book.

Silber: You definitely did. I’m Jewish, of course. I’m not religious, but it’s something I very much identify as personally. But this one question that I kept coming back to in that early section of the book where you’re talking about his difficulties with his family, and his rejection, not just religiously, but culturally of his heritage. I’ll ask this bluntly: was he ashamed of being Jewish?

Riesman: I don’t know. I can’t read his mind. I know he just didn’t want to be associated with it. When we talked about how he rejected religion in general, his way of describing it was, he just thought “if there is a creator, how could he have given us this ability to think so hard?” And then, people go into a religion just to get indoctrinated and ignore the real world. I don’t think that qualifies necessarily as shame. It’s more, just saying, well, this is a little silly and limited.

He certainly never turned down people saying, “hey, you’re Jewish and I like that.” I talked to this rabbi [Simcha Weinstein] who wrote this book called Up Up and Oy Vey, which is this lighthearted look at Jewish themes in superhero comics. He talked about calling Stan for the book. He got the number, got through to him at Pow! Entertainment. Stan picked up and, I’m paraphrasing here, but he basically said to Stan, “I want to talk to you about the Jewish themes in your writing.” And Stan was like, “I have Jewish themes in my writing? I don’t know what you’re talking about. But sure, that sounds great.” He just kept telling the rabbi “well, I don’t really know what you’re talking about, but, you know, sure. I guess that could be Jewish.”

So I don’t know if he was ashamed. He certainly didn’t think of it as something that was crucial to understanding him, although I would argue that it’s very crucial in understanding him.

Silber: Looking at this a little bit more from a fan perspective, you’re a journalist but I’ve talked to you and know you’re a big comics fan. Is there anything in Stan’s work that you think, for as much as there are certain things that maybe people are reading too much into in terms of potential Jewish influences, where you’re like, “OK, that right there” you know had to come from a Jewish mind?

Riesman: The closest thing would be just using Yiddish-isms here and there. And that’s really it. I mean, there isn’t a ton in Stan’s work, I think, that is uniquely Jewish. I think there’s a lot in Stan’s life that’s uniquely Jewish, a lot of his personality that’s uniquely Jewish. But in the product that he put out, I know others disagree, maybe Judaism or Jewishness influenced some of those stories, but that doesn’t make them uniquely Jewish. So we can’t really prove that definitely came out of his Jewishness, you know? They’re about such universal humanistic themes that it’s hard to attribute them to any one sort of creed or religion or culture.

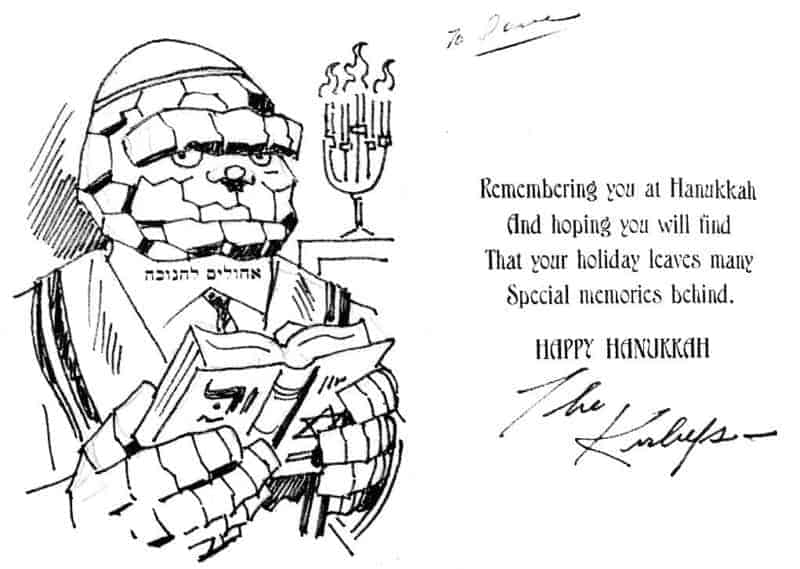

Silber: The Thing is an example that’s just pure Jack Kirby. I don’t think anyone would have much of a problem with me saying that. It’s a very clear inspiration from Kirby’s own Jewish Lower East Side background.

Riesman: Oh, yes, definitely.

Silber: But for me as a reader, the clearest indication I have of like, “okay, this had to come from a Jewish perspective” is Spider-Man, because Steve Ditko was not Jewish. And even though we didn’t have any “canonical” Jewish Spider-Man stuff until that Into the Spider-Verse movie…

Riesman: Oh yeah, Spider-Verse, definitely.

Silber: He lives in Forest Hills, Queens, which is traditionally a Jewish neighborhood. He speaks Yiddish with a lot more frequency than, say, Iron Man or Doctor Strange. I just don’t see that coming from Ditko in quite the same way.

Riesman: I don’t know, maybe you’re right. I never read Spider-Man as a particularly Jewish story. Maybe that’s just because I was too canonically-minded when I was a kid. But I’ve just never seen anything specifically Jewish. I’m not saying he’s deeply unJewish. It’s just that I don’t think anything there is a giveaway or whatever.

Silber: That’s fair. I’m not trying to put you in a place where you have to be like, “oh yeah, there it is!” But it’s the kind of thing that, when you read that much about that Jewish part of his life that up until now I don’t think anyone knew about — I didn’t know about the violence his family experienced or things like that — It’s hard not to look backwards and think about that stuff. But as you said, his entire family, other than his wife and daughter, he really didn’t seem to want much to do with them.

Riesman: No, he didn’t. It’s not to say he had no relationship with them. But by Larry, his brother’s own admission, they had a cold and distant relationship. He told me that he felt like he never really had him or didn’t really know him. Those are the kinds of words that he used to describe Stan. Stan didn’t get along very well with his father. Again, that’s by Stan’s own admission, but also by Larry’s testimony and cousins said similar things. And his mother died relatively young, in 1947 when he was still pretty young and just newly married.

So he avoided his dad. He avoided his brother and didn’t hang out with the cousins. Trust me, I got in touch with cousins. They were all like, “yeah, we’ve never met him. He just wasn’t on the radar for us.” His only real family was his wife and his daughter, about whom he was extremely passionate and deeply attached to. But everybody else faded into the background for the most part.

Silber: We’ve talked a lot about what Stan put front and center in terms of what he wanted people to see of him, what he may or may not have actually done, all that kind of stuff. But what do you think, purely in terms of Stan’s mind, whatever you might be able to estimate about it… what do you think he would have considered his greatest accomplishment?

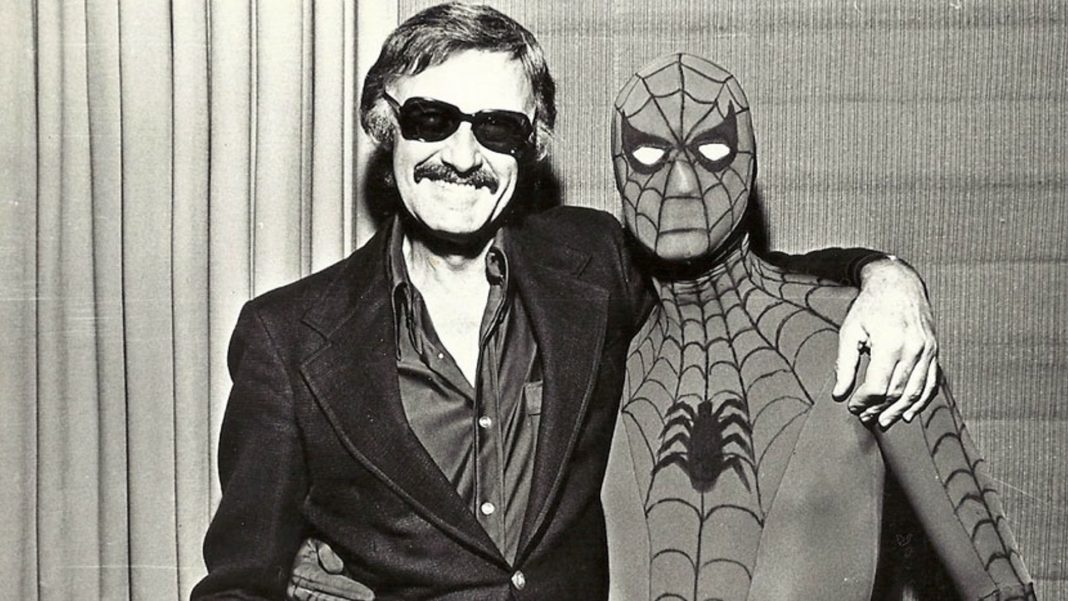

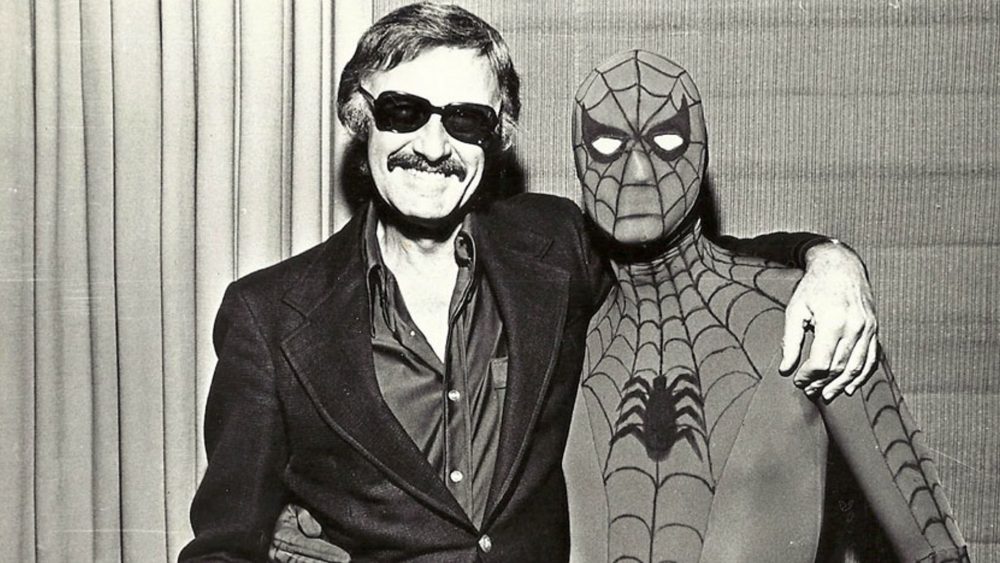

Riesman: That’s a great question. I mean, he was often asked about that and if you asked him what his favorite creation was, he changed it around but very often it was Spider-Man. He would talk about what an honor it was, in vagaries, about his accomplishments with Marvel Comics being so big.

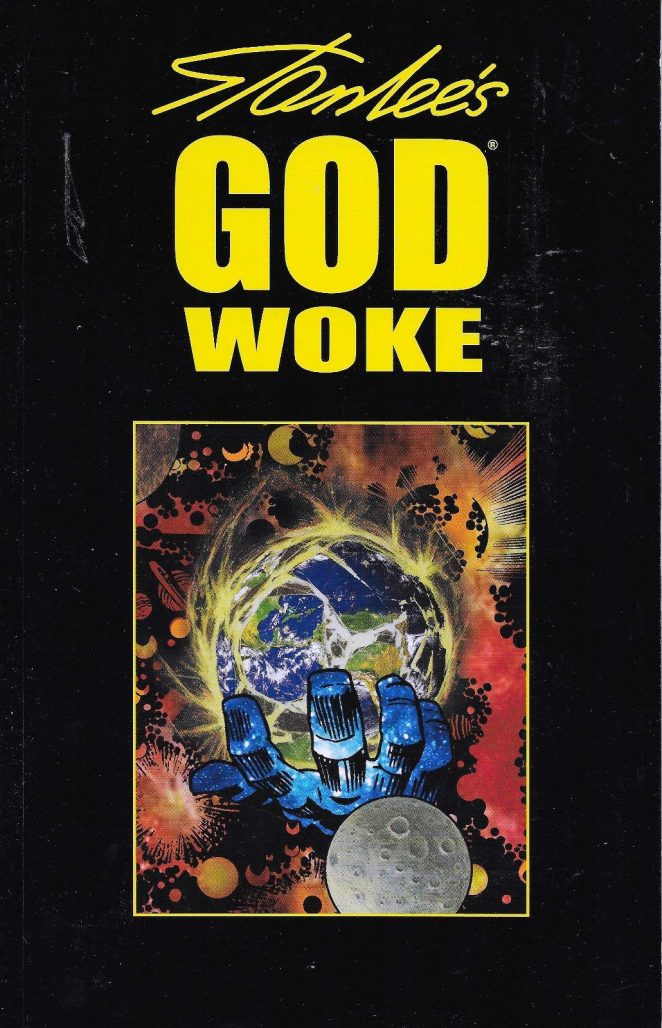

One thing that was very important to him, that he thought was about as close to a masterwork as he ever did, was this poem he wrote called “God Woke.” It was published eventually many decades after he wrote it in this book of interviews with Stan that was published at the small press. It was this poem that Stan wrote dating back to the late ’60s, early ’70s. It’s about G-d as an abstraction. He’s not talking about a religious vision of God. It’s God sort of surveying humanity and the world and judging them. It’s this very Silver Surfer-y type of thing.

Silber: Totally.

Riesman: He was very proud of that. But it never really got anywhere in terms of notoriety. It was read by his wife and daughter at the infamous Carnegie Hall show from 1971 where Stan was doing that one-man Show. But it took until, G-d, like 2007 or something for it to first get published. Then there was a comic based on it that came out a few years ago, but it never really caught on. One of his greatest works, if not the greatest.

So, yeah, you never know what people are going to be most proud of. It’s pride and personal respect. It’s a very personal thing. It’s very subjective. So, yeah, I couldn’t tell you, but I would hazard a guess that it might be something that you wouldn’t expect.

Published by Penguin Random House, True Believer: The Rise and Fall of Stan Lee is available now.

Great interview. I think I know quote a bit about Stan Lee’s life (thank in part to Abraham’s writing), but now I want to read this book ASAP. Oh, it’s out TODAY? Happy birthday to me!

Really enjoying these interviews, and am looking forward to reading the book. After reading a lot of articles about the history of the Marvel Bullpen in The Comics Journal over the years, I’m interested in what sounds like a more unified overview of the period (in regards to Stan’s involvement).

What a flaming pile of garbage, just like many comics this belongs in the fiction section.

Comments are closed.