The Beat’s Gregory Paul Silber has been accused of having a bit of an… obsessive personality. Each week in Silber Linings, he takes a humorous look at the weirdest, funniest, and most obscure bits of comics and pop culture that he can’t get out of his head.

On Saturday, October 9th at 6:30pm in room 408 of the Javits Center, I’ll be moderating my first New York Comic Con panel, and my first in-person panel, period. The panel is titled “It’s Clobberin’ Time: Great Comic Book Fights,” and it’s gonna be a ton of fun. My guests on the panel will be artist Jamal Igle (Supergirl, The Wrong Earth), writer and letterer Joe Caramagna (DuckTales, Frozen), editor Heather Antos (IDW, Image), and The Beat’s own Ricardo Serrano Denis. If you have an already-sold-out Saturday badge for NYCC, I’d love to see you there, too.

As Elton John once put so eloquently, Saturday Night’s Alright for Fighting.

I plan on letting my guests do most of the talking, so while it’s just you and me here I’d like to give my own perspective on what makes comic book fighting so fun. But before I do that, we have to talk about what makes fictional fighting so fun in any storytelling medium.

And before I do that, in the interest of preventing myself from getting yelled at on this here internet, I guess I should clarify what I’m talking about when I talk about how much fun fictional violence could be. Obviously, I’m not advocating for real-life violence, and watching or reading about it disturbs me much more than some might expect from someone who loves horror, action, and crime fiction as much as me. But even when it comes to fiction, context is crucial. The kind of distressing, grounded violence on display in a film like American History X hits extraordinarily differently than the stylized, fist-pumping adrenaline rush of The Matrix.

Clearly, I’ll be spending the panel, and the rest of this essay, discussing fictional fights that more closely fit the vibe of the latter. So now that I’ve avoided any uncharitable or bad-faith readings suggesting I’m some kind of bloodthirsty monster, why the heck do we love fake fighting so much?

I’m sure psychologists have studied the matter more scientifically, but from where I’m standing as a writer and critic, I think it’s rooted in the fundamental premise that stories are driven by conflict. It’s not so much that we enjoy seeing fictional characters in pain (although schadenfreude certainly can be appealing in fiction), but that it’s exhilarating when they’re in danger.

In less fantastical and stylized stories, or at least ones that are centered less around physical fighting, danger might be presented in subtler or more relatable ways. In a romantic comedy like When Harry Met Sally, Harry and Sally are in danger of losing the opportunity to commit themselves to someone they love. In a drama like Citizen Kane, the titular protagonist is in danger of losing his humanity to greed and egotism.

Genre fiction certainly can and should have similarly relatable conflicts. At the beginning of Die Hard, John McClane (Bruce Willis)’s greatest desire is to enjoy a nice Christmas with his kids despite the awkwardness between him and his wife following their separation. But the mundane meets the outlandish when said wife’s office is invaded by machine gun-toting robbers led by a cackling Hans Gruber (Alan Rickman), and John finds himself in a more immediate, primal sort of danger.

As much as we enjoy and appreciate the mundane dangers of more grounded, high-brow fiction, there’s a lot to be said for appealing to the audience’s primal side, too. For what I would wager is a majority of the people reading this, we don’t spend our day-to-day lives in mortal peril. We have health crises, sure, and terrible, horrifying things can happen to anyone at any time, but for the most part, we spend more time worried about our relationships, finances, careers, and the like than falling into a volcano or getting eaten by an alien. It’s exciting to vicariously watch characters go through fantastical experiences that we (probably) never will. Perhaps on some level, fictional fighting takes us back to our hunter-gatherer roots when the threat of getting stomped by a wooly mammoth was an everyday concern.

It goes to another level when we’re talking not just about fictional peril, but fighting. Fighting another person isn’t just dangerous, but in most cases, illegal. As much as I might want to fight the guy I’ve seen more than once on my commute who blasts EDM on a 7am subway and pretends he doesn’t hear anyone who asks him to turn it off, I can’t take a swing at him unless I’m willing to go to jail for assault. Which I’m not.

And even beyond legality, it usually just isn’t socially acceptable to start a physical fight. I’ve been in heated arguments before, but hitting the person with whom I was arguing has never been a serious consideration. I’ve only thrown a swing in anger twice in my life, and both of those incidents occurred when I was 15, a terrible age. Who knows, if there were no laws or social conventions in place, maybe I would’ve punched someone during an argument. Mostly, though, I don’t want to embarrass myself or those around me over something as petty as, for example, another guy’s bad Superman opinions.

Again, there’s a vicarious delight in watching characters physically fight, because that’s generally not how the average person resolves conflicts in the real world. It helps that genre fiction usually presents these fights as a sort of righteous anger. Luke Skywalker is right to be angry at Darth Vader in The Empire Strikes Back for a host of reasons. We wouldn’t cheer Luke on in all those lightsaber battles if Vader had simply expressed a bad opinion about his favorite band, Figrin D’an and the Modal Nodes, rather than, you know, being a ruthless enforcer for a fascist empire.

Which brings us to comics. Comics birthed the superhero genre, which may be more predicated on the concept of righteous anger than any other genre or subgenre. Superhero stories, in their most basic components, are quintessentially based around a righteous hero defeating a supervillain, often through cartoonish violence.

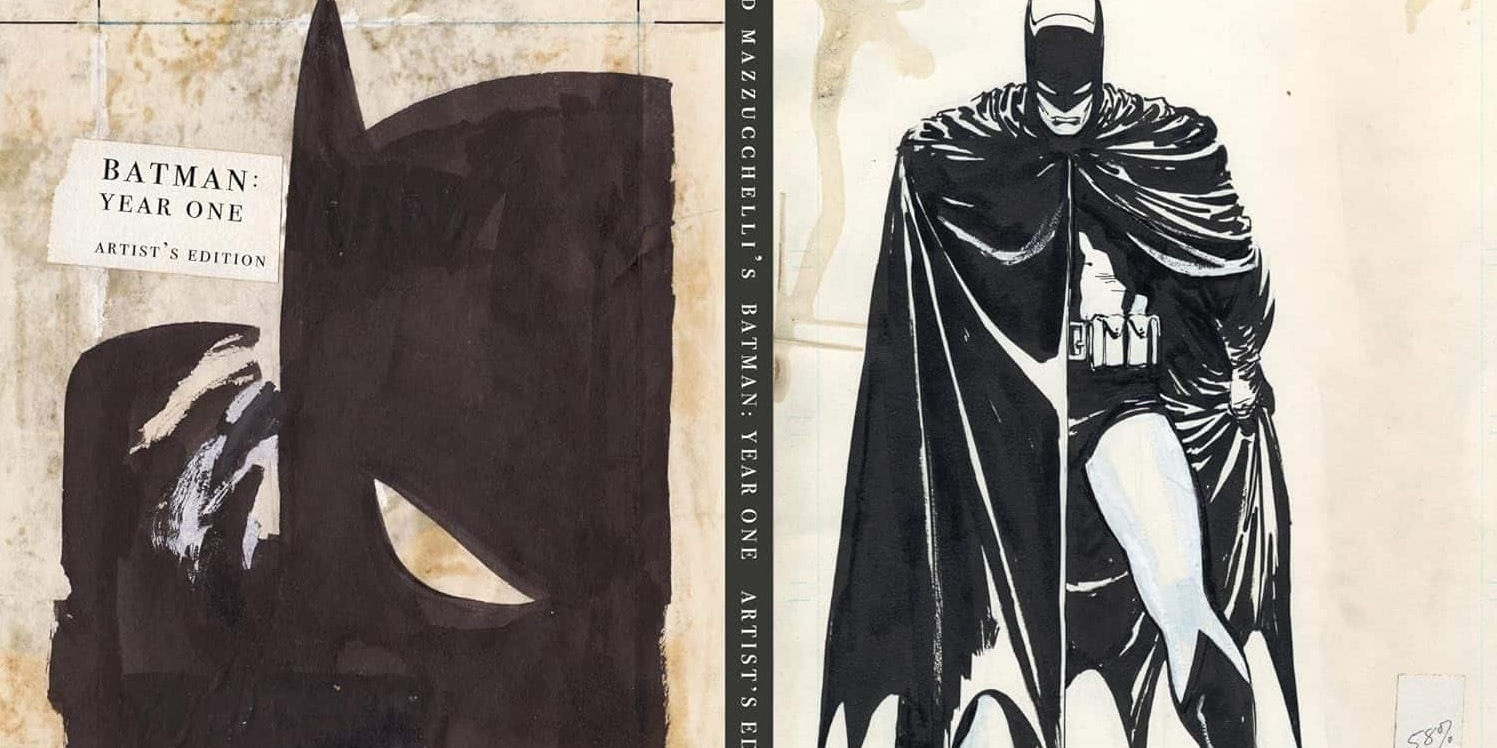

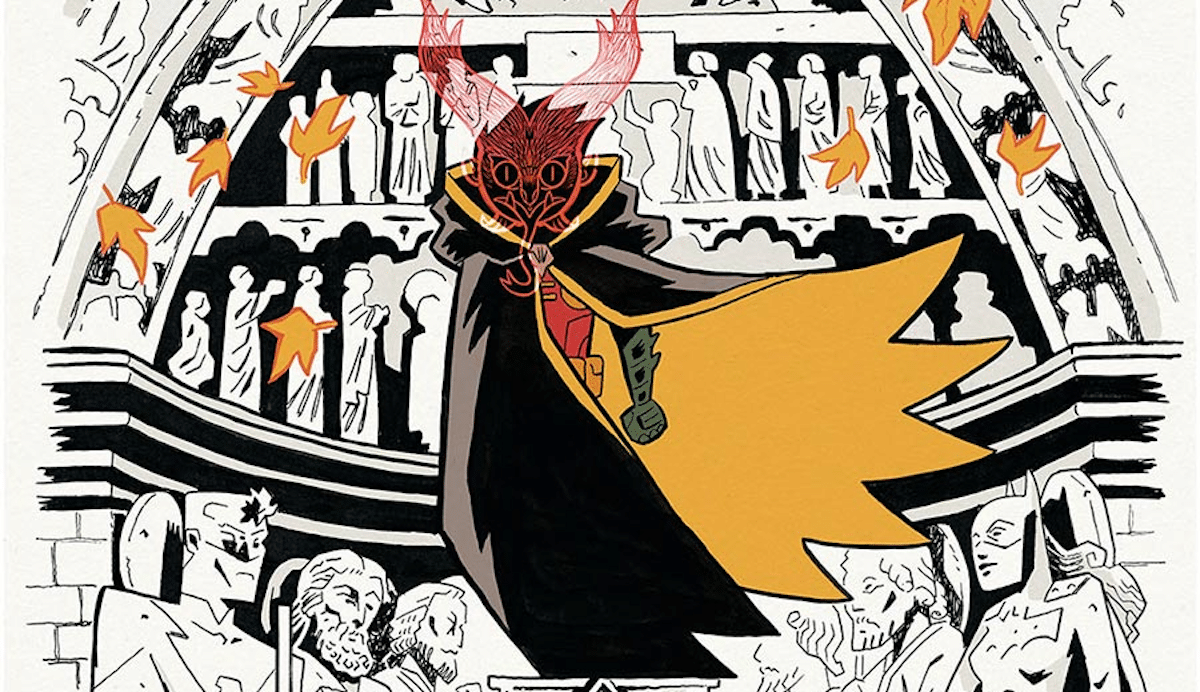

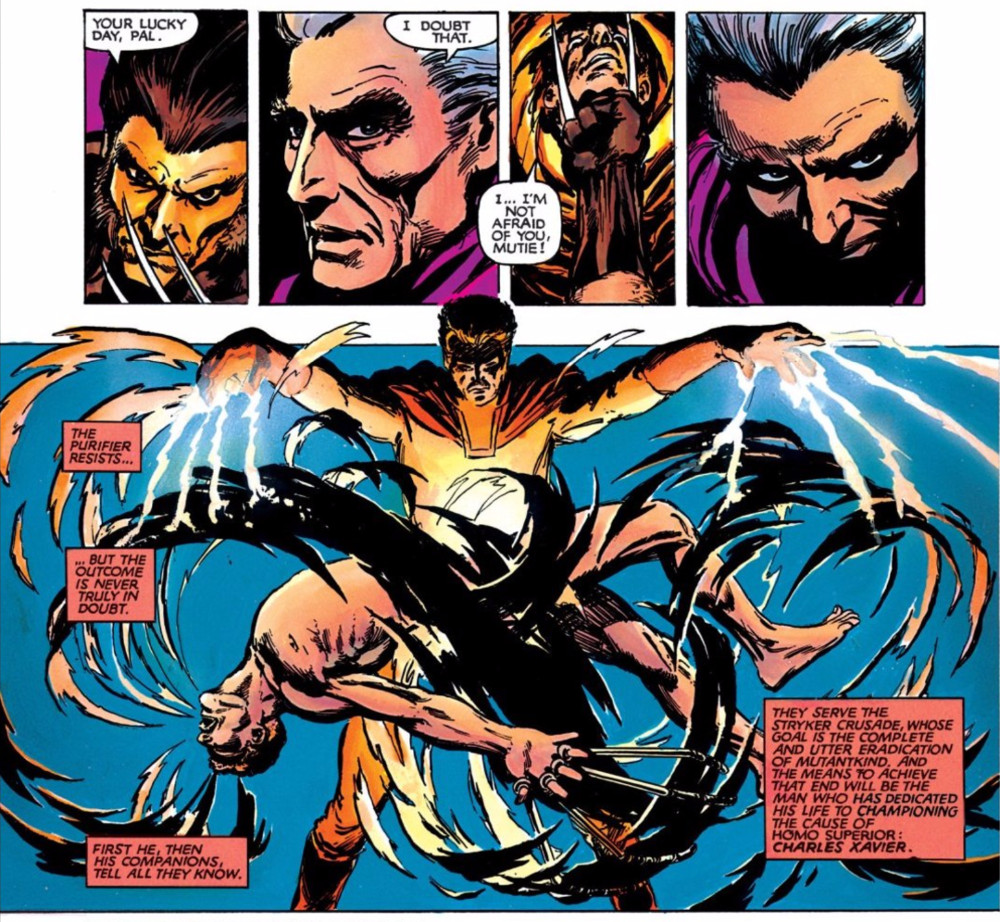

Sometimes it’s symbolic. Batman versus the Joker can be seen as order versus chaos. Or, if Kingpin represents the forces threatening to ruin our lives in Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli‘s “Born Again,” than Daredevil is the avatar of the defiance of the human spirit as we fight to build ourselves back up. And it doesn’t even need to be that much of a metaphor. The X-Men’s fight against William Stryker in Chris Claremont and Brent Anderson‘s God Loves, Man Kills represents the struggle between marginalized people and theocratic fascism because the X-Men are canonically marginalized and the Stryker character is, well, a theocratic fascist. It’s fun to see such bluntly literalized representations of our ideals versus humanity’s greatest fears and sins. It helps us make sense of things that can be too scary or confusing to think about on their own terms.

The magic of a great novel is that you, as the reader, have an incredible amount of control over how you imagine the story playing out. An author tells you exactly what to imagine, often with painstaking detail, but ultimately, the responsibility falls on the reader’s own imagination to create the fully-formed world within their own heads.

Film, by its nature, offers a more passive storytelling experience. That’s not to say audiences can’t or shouldn’t exercise their own intellect and creativity while watching a film to fully engage with its themes or craft, but that there’s fundamentally less ambiguity. We know exactly what these characters look like, how they talk, and what music they hear when they enter a room. And crucially, there’s relatively little mystery to how things are timed and paced.

That’s different with comics. When we read from panel to panel, we have an unrivaled control over the pace. Savvy comics creators are clever about how the pages suggest pace, but the responsibility falls on readers to determine whether a comic book conversation took two minutes or ten minutes. There’s such artistry to balancing how much or how little detail you give readers in a comic. Fiona Staples draws richly-rendered sci-fi fantasy worlds in Saga, but when you close your eyes and try to imagine Alana and Marko as real people, perhaps they look a little different, or like someone you know in real life.

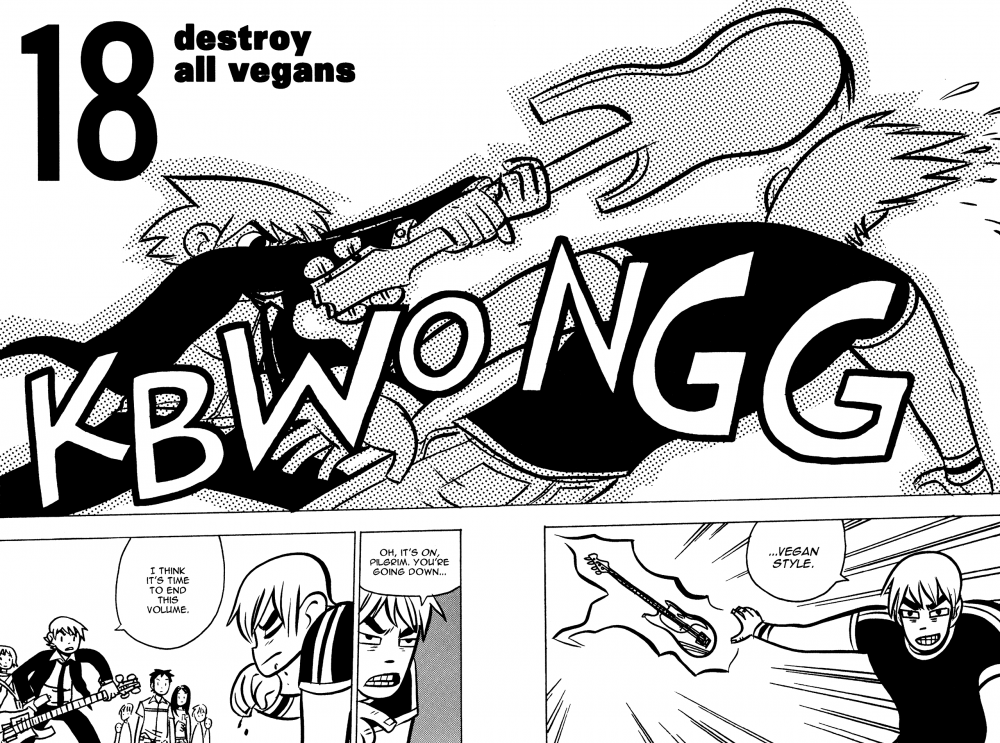

Sound effects suggest sonic sensations, but when Scott Pilgrim plays bass in his band, what does that actually sound like to you? If you watch the film adaptation of Scott Pilgrim Vs the World, it sounds like Beck, because those songs in that movie are literally written by Beck and you’re hearing the songs Beck wrote. But if you’re reading the comic, perhaps you think Scott’s band sounds more like Fugazi. Cartoonist Bryan Lee O’Malley does a great job establishing an aesthetic and vibe throughout the Scott Pilgrim graphic novels with his words and images, and all it takes is an extra push from readers to make it a fully-realized world.

Perhaps someday, we’ll get a live-action fight between The Incredible Hulk and The Thing in the Marvel Cinematic Universe. I’d be surprised if it hasn’t already happened in animation. But it won’t measure up to the fight as it’s drawn by Jack Kirby, with dialogue by Stan Lee, in Fantastic Four #25, and it’s not even just because Kirby was arguably the greatest artist of comic book fighting to ever live. It’s because nobody could ever film anything as awesome as that fight as Kirby allowed it to play out in our own heads.