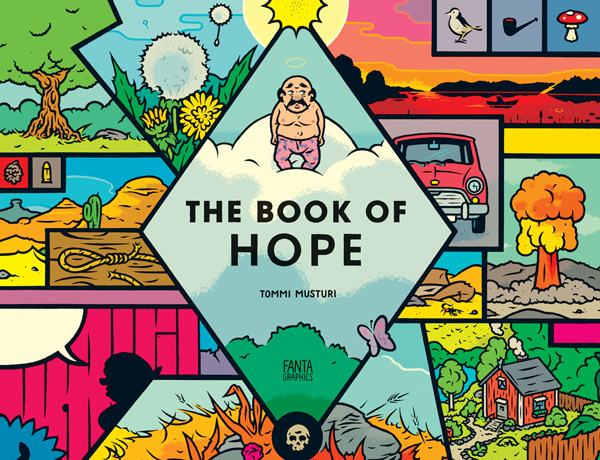

Finnish cartoonist Tommi Musturi’s The Book Of Hope is as mysterious and elusive as the human being it examines. Set in a family cottage following retirement, Musturi settles into his narrator position calmly in order to scribe, without judgment or even much push for clarity, the experience of one man as he inhabits the time near the end of his life.

Not literally — at least, it doesn’t begin with a diagnosis and then shift to a struggle with an impending mortality. This is more the anguish that taunts each of us as we age. We reach a certain point in life and the end becomes a fuzzy presence we can just make out on our personal landscape, unclear but definitely looming. We’re left to wonder what it will look like when we get closer, and whether it will manifest in some way that is poetic in contrast with our past, or counterproductive to finding any larger meaning to all this life we’ve lived.

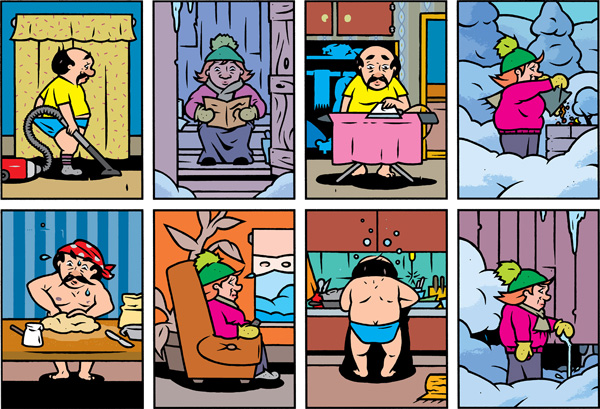

The man in Musturi’s story — squat, mustachioed, a bit like a Mario brother — lurks around the tranquil grounds of the cottage with less than a clue of what to do with himself. The surrounding silence doesn’t mean silence inside his head, where there is a rush of activity trying to figure out what to do with all this time and space. He’s obviously never had either, and his life, as it is for so many, was busy enough that there was never a moment to contemplate the next move. Not really.

But now there’s a moment, lots of them, and the man is finding out just how debilitating that can be. All he can do is grapple with the burdens of pondering, remembering, and fantasizing, so at odds with just taking things easy.

The first half of the book is less a narrative than extended, self-reflective poetry stretching its contemplative navel-gaze to the general state of human life into a philosophically expansive examination. Fantasies soon overtake this, offering alternatives to what has been lived, and then move into a calm representation of the present, not so much gloomy as delicate and quiet.

His wife is a phantom in the first half of the book and this distance, both physical — we know she exists, but always outside the panel — and emotional, gives the reader one impression of her, probably hostile or at least aloof. When she finally appears though, the reality of the man’s world is completed, she is not exactly who we thought she was and so, by proxy, neither is he.

Musturi’s colorful art paints a vivid world for this intense self examination, always struggling against the man’s focus inwards to divert his attention to reality. The depictions are cartoonish and melancholic, and Musturi is as adept at presenting a flurry of pop culture parody as he is the rich scenery of the man’s surroundings. In jumping from the real to the unreal, inside the mind and outside, there’s a lot of visual information to take in, By the end, we see that Musturi has mapped out how complicated any of us are, as part of the physical world and part of one or many relationships. We’re all walking bottomless pits of hope and regret and thankfulness. It’s a vivid meditation with good humor and no judgment, and that’s where the hope comes from.