Anytime I encounter a story with animals dominating the world in an aggressive stance against primitive humans, I can’t help but compare it to the two gold standards of my childhood, Planet of the Apes and Kamandi the Last Boy on Earth. The former, at least the first movie in the series, was thoughtful and philosophical within the framework of a science fiction adventure. That along with its insistence on portraying the apes as real characters is, I think, what has kept it in the public imagination beyond the more obvious reasons.

Kamandi, which Kirby was obviously inspired to create because of his fascination with Planet of the Apes, was a little more pulp-y, with broader and often more absurd satire delivered within the same framework, but a lot more over-the-top. It was actually perfect for the era and the age I was, offering social critique that was easily digestible to a simpler time with more complicated implications to its unfolding.

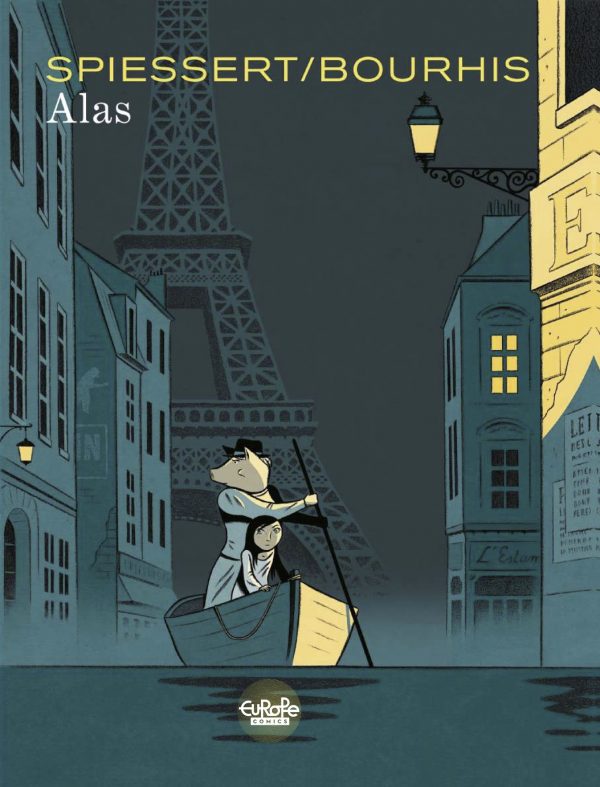

These two were obviously on my mind as I read Alas, a new digital release from Europe Comics. Originally rendered by French creative team writer Hervé Bourhis and artist Rudy Spiessert for the Belgian publisher Dupuis, I came to it with a lot of nostalgic baggage, and I wondered what possible hope it could have. As it turned out, a lot.

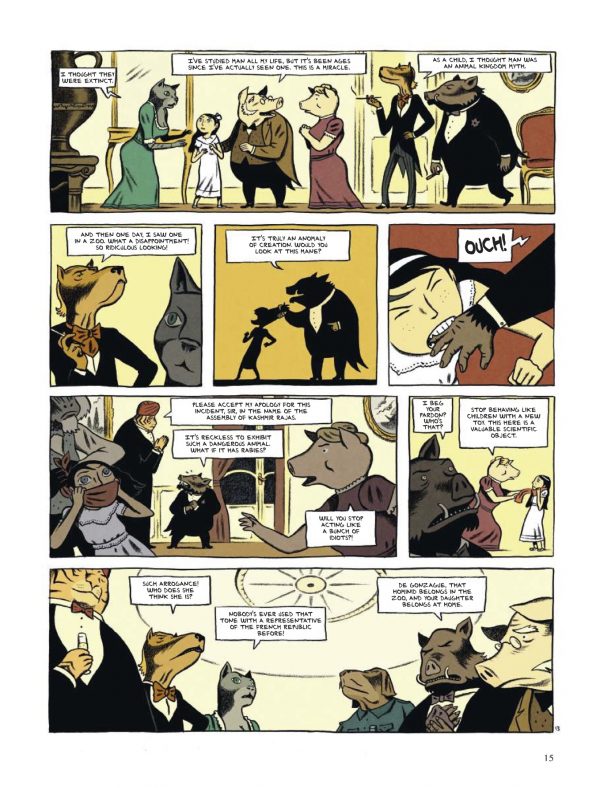

Alas might tread similar territory as those two favorites of mine, but its sensibility is fresh and the insights it offers are thankfully modern. Whereas the previous two works are from another era where human dominance is accepted as the norm even if it criticizes human society, Alas comes to the trope from a more enlightened place of animal rights and compassion, one that acknowledges that there is nothing inherently wrong with humans not being at the top of the food chain, but also uses its topsy-turvy reversal of actual circumstances to reveal a larger truth about empathy, either cross-species or from human-to-human.

Taking place in 1910-era Paris dominated by multiple types of animals, Alas centers around the capture of two human children and their distribution through illegal poaching. A wild chase between various factions erupts, all trying to find the children for their own purposes, but the ones we are rooting for are two pigs — Leopoldine, the daughter of a researcher in humans, and her would-be suitor Fulgence, a reporter investigating the human poaching.

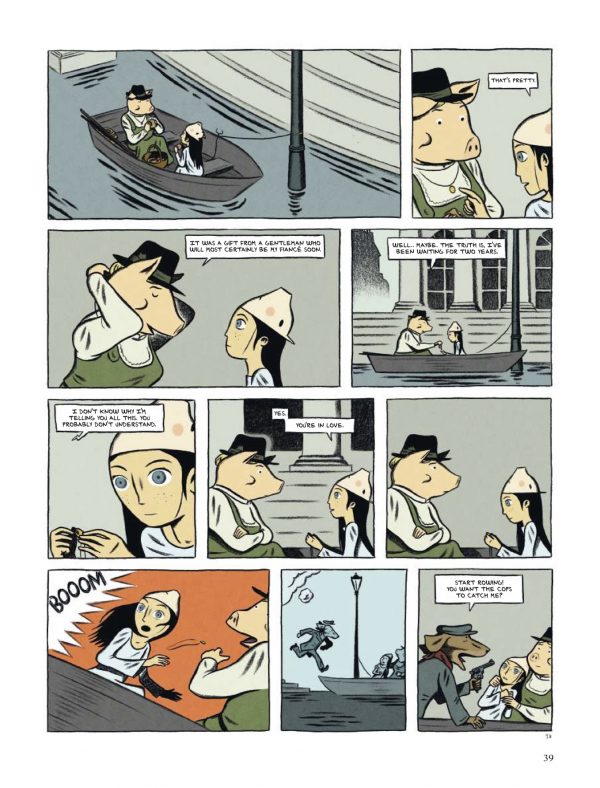

It’s Leopoldine and Fulgence who bring us closer to the human girl, who we find out is named Leaf, and revelations about the current state of humans, but that’s during a flurry of activity made more frantic by the fact that Paris has flooded and any hopes of escape, any manifestation of chases, only happen in boats. The story unfolds in a semi-post-apocalyptic Parisian landscape, as we get to know our well-depicted pig protagonists along with the sorry humans of 1910.

But rather than just remain a madcap adventure with an interesting subtext, Alas goes into some dark territory that mixes well with the good-natured energy of the suspense section. In explaining how we got to this point in the story, there’s lots of intriguing backtracking over the history of humans and animals, mixing parallel historical details into something more powerful than conspiratorial terms, and eventually, in the grand finale, taking us someplace very dark indeed that has similarities to our own current relationship with animals.

Bourhis’ dialogue is alternately hilarious and mesmerizing, depending upon which is most required at that moment, and Spiessert’s art is charming and energetic, with great work on the animals and cityscapes amidst the flood.

The adventure ends here, but there’s a hint that there is more to come. Certainly, the history laid out, the implications of that history, and the engaging characters who traverse the adventure have offered an intriguing mix. I can certainly say that there is no reason this story shouldn’t continue, and I would be disappointed if it doesn’t.