In Gipi’s post-apocalyptic drama Land of the Sons, there’s a moment when a father laments whether he should reveal to his sons that dogs were once prized friends of humans to be cherished and not competitors for resources that you killed for food. The fear is that to reveal such a truth is to acknowledge a form of empathy that creates weakness in a world where survival at all costs has become crucial.

What becomes apparent is that the situation is the same with children. Whereas in the context of the story, children were once indulged, they are now objects meant to help with survival. They are more mouths to feed, sure, but their addition to the efforts to provider make it more likely everyone will feed.

Which is how it use to be. The idea of children as precious, and of dogs as pets, at least for every family that chooses to have them, is a fairly new one. The place of children in the family was to provide, either in the home and out of the home, and dogs had jobs as well — guarding, hunting. A family unit was a practical unit, designed for work. And so civilization of the past in linked with our perception of what a nightmarish future would be. Our biggest fear is that we will be forced to degenerate into what we think we’ve finally moved past.

In this context, what we’ve moved past is placing humans into roles as practical tools, and Land of the Sons is an examination of what happens when tools are left to their own devices. Tools without context, tools without a user.

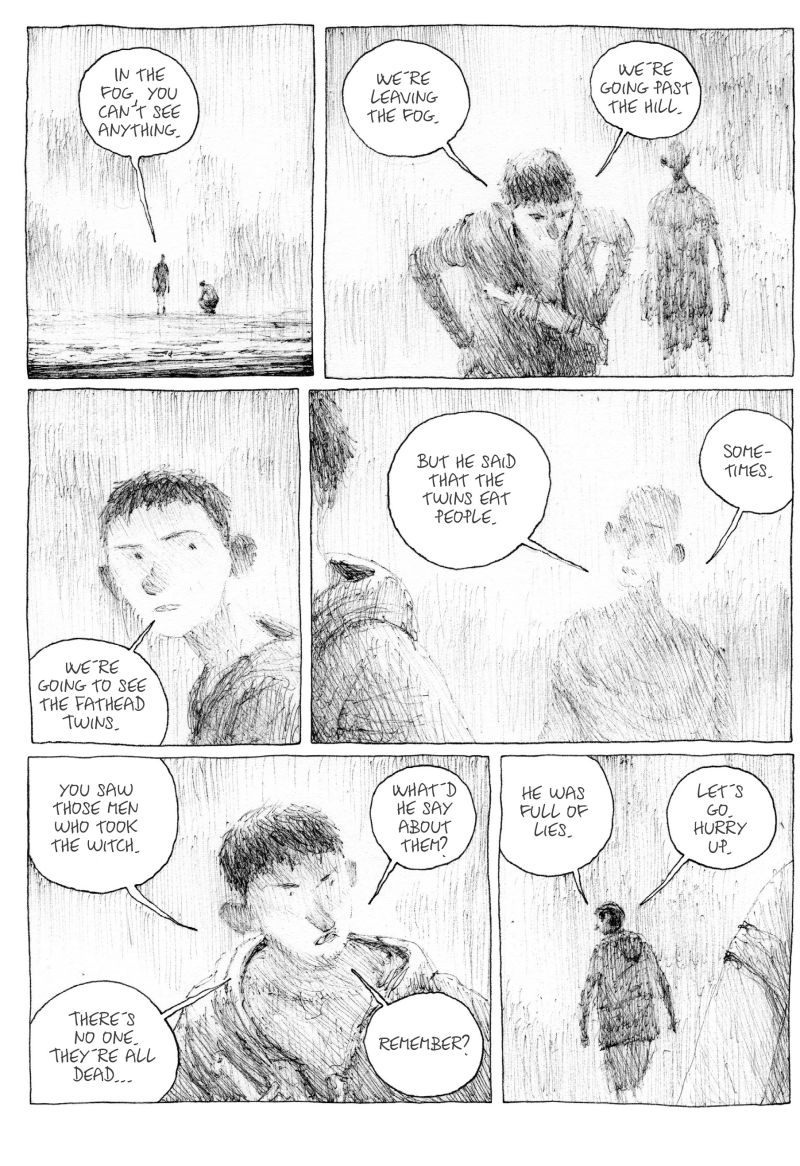

In the story, the father lives in isolation with his two sons, directing their actions but providing little in explanation other than short rules for them to follow, such as never crying. The more in-depth observations of the world, and the context he brings to their experience as a unit are kept for a private diary that he uses threats against them to keep out of their hands. But as someone who isn’t passing along the tools the sons need to continue civilization, he doesn’t teach them to read, so the diary isn’t much under threat anyhow.

But when the moment comes that the boys can and want to and maybe even need to uncover what is in their father’s written word, their inability to read and their need to rely on other people to reveal to them their father’s secrets are what places them in danger. For all the efforts of the father to keep them separate from whatever clutter they don’t need for survival, it’s the necessity of that clutter that threatens to undo the hard work the father has done.

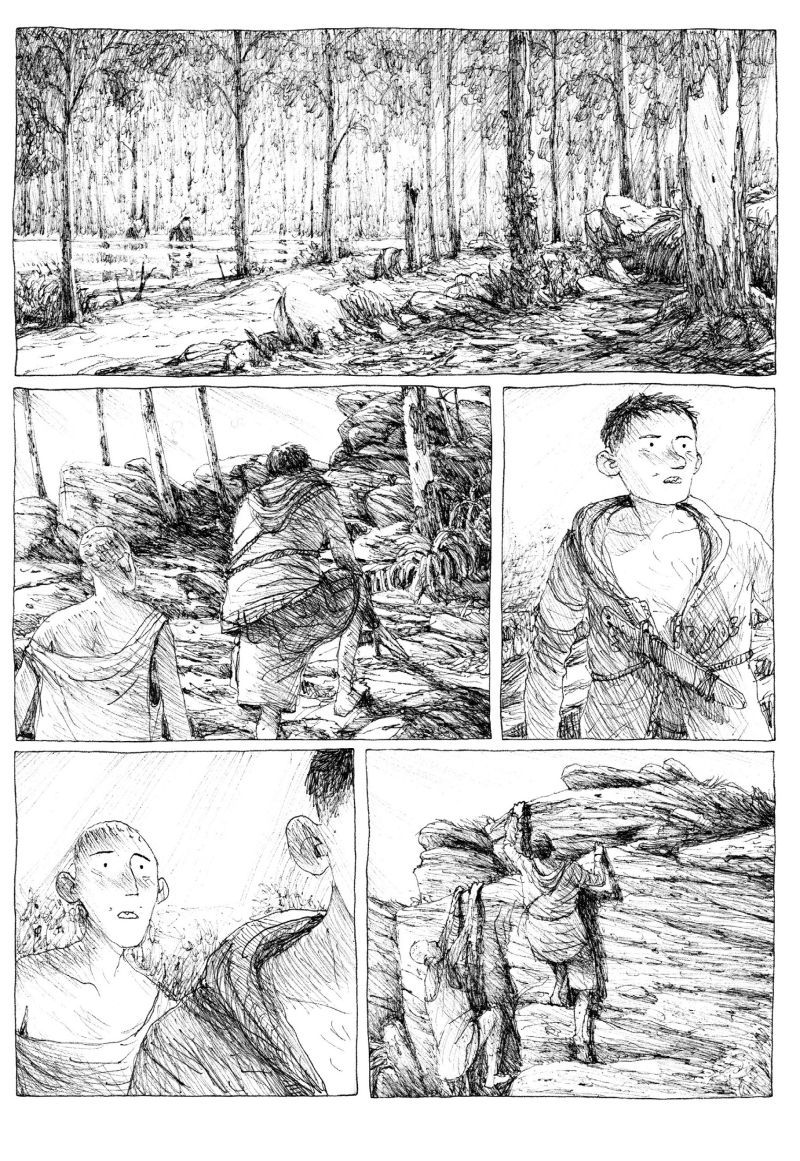

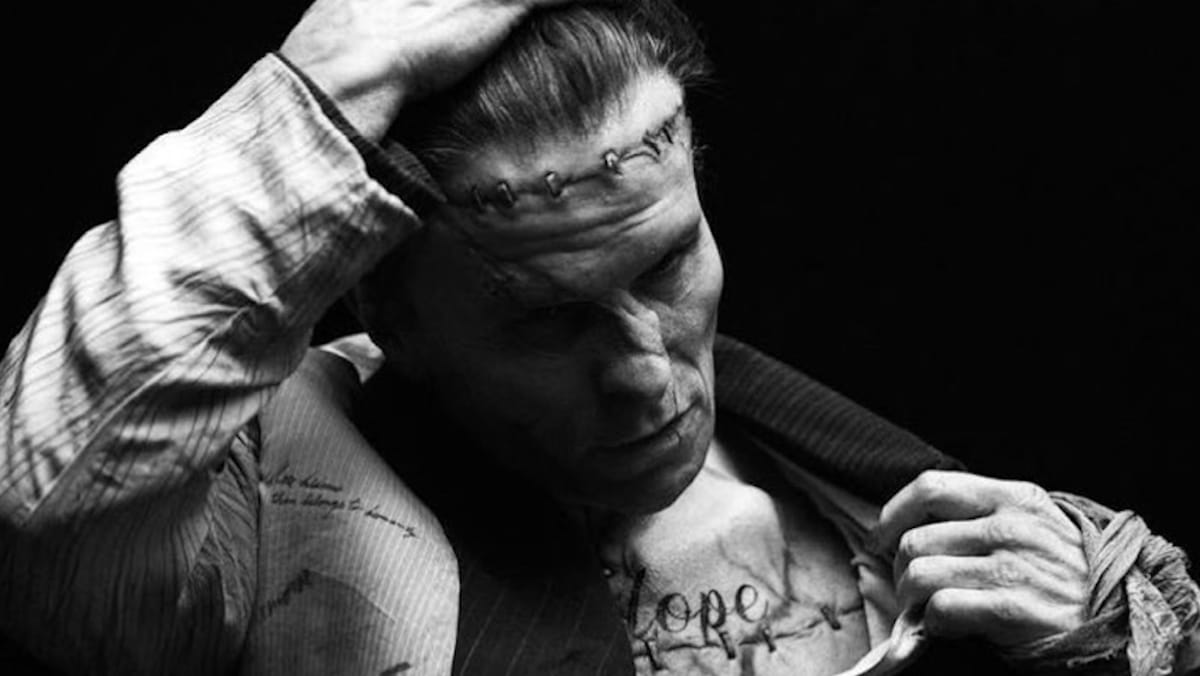

The world that Gipi has fashioned unfolds in his scratchy black and white line work, a bleak and barren landscape populated by an expanse of emptiness and tiny unkempt figures crossing it. There is nothing uplifting about the world in which they wander, and the silence that Gipi depicts in it is as oppressive as anything. Loneliness and insularity seem to be the central human condition of this world, and that makes the survivors here ill-equipped to combat dangers that might not be so stark and obvious in their presentation, within a world where humans have been relegated to the role of dogs, and dogs function as nothing more than food.

More than anything, Land of the Sons is the story of the first step to regaining some aspect of humanity, which will only come from a genuine connection. Connection is the only way that information is transferred and qualified, it’s the only way that wider priorities are created.

Bless the publishers for getting more Gipi into the market. He sadly does not sell big in the States, but each book is a treasure.

Would be nice to see the translator – Jamie Richards – acknowledged at any given point in the review!

Gipi is indeed a treasure. How come no one buys his stuff? The same with Blutch. And what about Baru?? Has any of his stuff been translated?

Comments are closed.