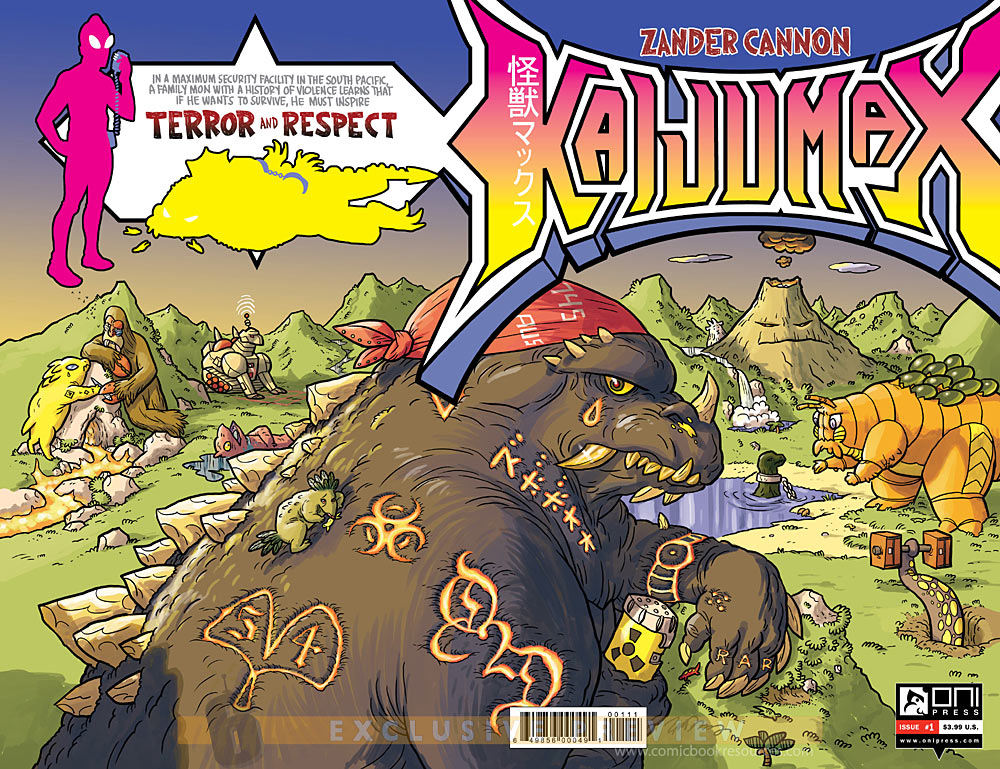

Zander Cannon has been hard at work on his series Kaijumax in 2015, which he writes, draws, colors and letters. He’s delivering odd, amusing, poignant stories about Godzilla-like creatures in a jail designed by men, the real monsters. I interviewed him about the series, how Oni Press makes for a good partner and more.

How did you come up with the concept of Kaijumax?

I had wanted to do something with monsters for a long time; I really liked the implications of all the kaiju movies regarding the hierarchies of the monsters (Godzilla being the King, for starters) and liked the idea of what they might get up to when they weren’t doing their usual attacks on humanity. I’ve always liked non-human characters, and I like that it gives a story a peculiar tone right off the bat. Once I had decided on that, I needed something to anchor it as a story. I had really enjoyed working on Top Ten with Gene Ha and Alan Moore, and when I wrote the series later, the thing I really fell in love with was that the fantasy and science fiction aspects were there as a matter of course, and it was the human interactions within it, and the genre conventions of a police drama, that drove the narrative. So when I looked at the logistics of how I could keep the monsters on the island and highlight their interpersonal — or inter-monster — relationships, I started thinking about another genre — prison drama — that I always liked, but never had a reason to write.

How did it land at Oni?

I’ve known the people at Oni from the very start, and have always liked their line of books. I had been doing a lot of work for DC and other bigger publishers with my eye on the bottom line, and I had kind of overlooked the smaller and middle-sized press for several years. But it was starting to become obvious that I’d never be happy at the larger publishers, trying to make sure I had a perfectly rounded, four-quadrant book that needed to sell X amount or be immediately cancelled. I wanted to go with a place that had the same ideas in mind for where the book would go, to whom it would appeal, and so on. The idea that I could do everything on it — and adapt the schedule accordingly — was the major seller.

What makes Oni the right partner?

Oni sits in a pleasant middle ground between the biggest publishers and the smallest. There’s a little money so that I can afford to live while I draw this comic, but there’s also an appreciation of things that don’t have to be mega-best sellers. With a smaller staff, they can champion peculiar books like mine and spend some effort finding the right audience.

It’s not awfully hard to guess which monster movies inspired the comic, but what prison fiction (or nonfiction) served as inspiration?

I had watched a great deal of Oz in preparation for this book, as well as Orange is the New Black, which was coming out just as I was getting going on it. I read Prison Stories by Seth Ferranti, which captures a lot of the rhythms of prison life, as well as showing an excellent ear for voices. I found that book fascinating. And there are a great deal of prison movies which are pretty great, like Cool Hand Luke and Escape from Alcatraz and the Shawshank Redemption, but I found I enjoyed the ones that were less about escape (and less about white heroes) and more about inevitability, drudgery, and unfairness.

Humans being the real monsters is a common trope. How are you delivering that theme in a unique way?

Well, it’s pretty unavoidable, so I made it the very first joke of the book (Electrogor roaring to his captors that THEY’RE the monsters!!). Beyond that, I wanted to scale it back somewhat. Very rarely will I accept that large swaths of individuals are — to a man — absolutely corrupt, but the idea that prison is an unfair system with reasonable and unreasonable characters on both sides, each contending with their own problems, gives me a lot to work with.

How does the very animated and cartoony art compliment the mature themes?

It’s hard for me to answer that, because it was not a particularly intentional move. I draw in a pretty cartoony style that — I like to think — can edge into dynamic realism, as well as humorous exaggeration, where needed. I do like that my cartoony style can sidestep a lot of potential complaints about the logistics of the world, because it’s right there on the page: this isn’t realistic! And from a time point of view, it allows me to focus time on things that provide scale, depth, emotion, and meaningful detail, rather than a lot of surface detail that has to be there just because it was there in all the other panels.

Some people have commented that they feel like the art style softens the blow of the harsh story details somewhat, and others say the opposite: that it blindsides them since they were expecting something sillier. I like to think of the style of drawing as simply being a very subjective style; it allows us to get in the head of a character and see things from their perspective, rather than focusing on details and texture above all else. And from my point of view, that’s the best approach to fiction.

Have you dealt with any complaints that it seemed like a kids comic at first glance?

Sure, plenty. The book was billed as a bit of a comedy, and a lot of the early hype — even if it mentioned that it’s kind of sad — played up the monster/prison mashup gags, because why wouldn’t you? I think this got a lot of people on board who were ill at ease later with some of the harsher, more prison-like aspects. I can’t blame people for that; I have certain comics that I stopped buying because they were too grim or unpleasant, as well. I do think that the stuff that’s gone down in the comic is within the parameters I’ve set for the series; nearly every bit of cruelty and gruesomeness can be found in a monster movie somewhere — mostly in the made-for-kids ones of the 60s and 70s, even!

The lettering and design work is pretty complex, especially since you (the artist) are doing it all yourself. How were you trained?

I can’t take any of the credit for the design; the inside front cover or the letters page are all Fred Chao, who has the unenviable job of waiting until I’m done drawing the pages before he can even start.

As for the rest, well, I trained on the streets, man! I didn’t go to art school or anything like that because I had no interest in “real” art. I started by drawing comic strips for my college paper, and basically just stared at great comics until I could kind of reverse engineer how they did them. From that point of view, I feel like I’m not particularly good at certain things that require a bit of academic learning, like design or color theory, and that I’m quite good at things that require a bajillion hours of practice, like writing and drawing and lettering.

At this point in my career, I think it’s important for me to be able to do everything in a comic, whether I do it or not, just so I can understand what’s being done and what’s being asked of each person. I never like being a burden on other people, so if I have to push something off on someone, I want to know that it’s possible to do it in that amount of time.

Being a one-man show is kind of the opposite of the conventional thinking, in terms of trying to make a living in comics. I think it’s generally thought of as much more efficient to focus on one thing and do it over and over. I’m sure that’s true, but I tried it (both as a writer and as an artist) and I couldn’t do it and it was terrible.

What benefits as both a writer and artist does being the letterer provide you?

As an artist, for one thing, it means I can cover up big chunks of background with those word balloons and never have to even think about them! You may think I’m being glib, but that is absolutely a huge advantage. I have pretty talky books, and I have no interest in drawing anything that’s not going to be seen. On a more subtle note, putting in and inking the balloons at the same time that I’m inking everything else means that 1) I don’t end up getting a bunch of awkward tangents with the balloon edge and art elements, and 2) that I can balance the light and dark of the panel more effectively since I see, rather than just generally know, what it’s going to look like in the final version.

As for being both letterer and writer, the funny thing is that it’s reversed. It’s a huge advantage to letterer-me that I’m also the writer, since if a balloon is not fitting very well, I can trim it down or tighten the wording. And if there’s an empty corner to the panel, I can just write up another word balloon and stick it in rather than having to run the idea by four people.

The owners of Challenger Comics have talked about how they got behind Kaijumax in a big way because of how much they liked the book. How do you gather support for the series amongst comic book readers and retailers?

That’s when it’s a terrific advantage to have a publisher like Oni (and an editor like Charlie Chu), who has a small line and a great interest in each of their books finding its audience. I’m always happy to do things to promote the book, but I’m also frantically trying to get the book done, so it’s nice to have a publisher coordinating things and thinking about where best to apply the things that I need to do.

Challengers Comics has been super supportive, both of this book and of all my work over the years, and I owe them quite a bit.

How is your connection to the series different as the sole author of the book? Does it mean more to you than something like Top Ten on some level, or are they two entirely different animals?

Well, they’re different from the start since I own and control Kaijumax. I know that’s not a terrifically creative thing to say, but that does make a big difference in that it allows me to look down the line a bit and not just hope that it doesn’t get cancelled or given to someone else.

Being the sole author has a great deal of creative advantages, particularly in terms of being able to make the book exactly what I want it to be at any given moment. I don’t have to make a grand pitch to all my collaborators to make sure that they’re on board if I want to move the focus to another place or another character. Obviously those controls are good in a lot of instances, but they do slow things down.

Top Ten meant a great deal to me; I really enjoyed getting into characters’ heads and fleshing out that world and giving every crime a superhero equivalent. That was what was on my mind when I created the idea of Kaijumax; I like that I could have a rich world that was familiar and completely bizarre at the same time, but this time I could completely control it and not be (as) beholden to forces outside my control. It’s also really gratifying to have people’s reaction to it really be reactions to my work. If they like it, they like what I’ve done. If they hate it, that’s on me too. When people comment on an experience that I’ve engineered, it’s much more valuable to me than if they think my drawing or dialogue is nice.

I’ve got to take the first paperback of this, especially seems it seems that Oni is usually offering a nice deal on their first paperback of a serie.

+ Zander Cannon is extra cute, you should have put on a picture of him inside the article. Handsome smiling artist sell more than the others :p

I’m loving this series so far. It’s gorgeous and funny, yet weird and strange all at the same time.

Comments are closed.