Cartoonist, comic critic, and editor Claire Napier is crowdfunding a new one-shot on Zoop, The Magic Necklace, an adult-only (18+) horny horror romance story about sexual danger, desire, relying on men, and bargains we make with ourselves and others. As of today, there are 17 days left to support the campaign.

The Beat had a chance to speak with Napier over Zoom to discuss the project, and we have been listening to Alice Cooper‘s “Poison” on repeat ever since. Read on to learn more about the inspiration behind Napier’s The Magic Necklace, her decision to accent the issue with hot pink, the nitty-gritty of life, and more!

This interview has been edited for clarity and conciseness. Please note that this article contains a discussion of sexual assault and stalking.

Rebecca Oliver Kaplan: The Magic Necklace wasn’t what I expected; it deals with some heavy topics in a really relatable way. The way he touched the lead character in the book’s introduction is an experience I’ve been through, and it didn’t feel great. So, can we talk about why you chose to use a comic to explore sexual assault?

Claire Napier: I’m pleased to hear that you didn’t take it as sensationalism because it can be hard to show things that happen without scaring people. Although, of course, it is a horror romance, so it’s supposed to be scary.

[My decision to use comics to explore that topic] wasn’t so much of a choice as it was inevitable. I make comics, and comics is my area of focus. I have been writing comics criticism for ten years and am a comics editor. I was a comics fan long before that, from childhood. Plus, I’ve always drawn, so when it comes to making art and fiction, I do it in comics because, as a cartoonist, you can do it on your own and not have to negotiate anything. It’s just between what you can get onto the page and what you can’t, and if there’s something that you can’t, then can you somehow imply it through the page? So it was natural to approach sexual topics through comics because you can barely read a comic without getting some sexual theme.

Much of my reading has been about superheroes, and much of my writing has been on superheroes, and superhero comics are often inherently sexual. Whether or not that’s provocative or not, it’s usually chaste — they hold hands and kiss at the end. If someone’s going to have sex, it’s off-screen, a fade-to-black kind of thing because, as I said, they have rules. But that aside, there’s so much sexualization within the mainstream American, French, and Japanese comics markets, well, probably any market, because misogyny and sexualization are inherent to the patriarchy, and most places have that.

I became a professional because I had things to say about comics and the things that were in comics; much of my writing is about portraying women, gender, and sexual objectification in comics that aren’t about that at all. Instead, they include that reflexively in a very unreflective way, which peeves me—I’m disdainful of it. Like, it’s not a complete gap [in the range of representation] since there are comics that do what I do; it’s just not as many as the kinds that I want to talk about as a critic and reflective reader.

I couldn’t have made this comic without giving my time to comics scholarship, journalism, and commentary. I wouldn’t have had the thoughts I’ve had if I hadn’t been responding to the horrible stuff there. I would love to be the kind of person who makes a nice comic, but that’s not what the world asks of me.

Kaplan: Did the storyline come from personal experience? It feels authentic.

Napier: That’s a huge compliment that it felt real. It’s not autobiographical, it is based on movies. I wrote about this on my Patreon, but I like to do viewing seasons where I watch a lot of movies with the same theme. We hit a period of erotic thrillers. As with anything, I’m very picky, but a few liked it. Obviously, we tried to watch both men’s and women’s ones, like True Crime, also known as a Dangerous Kiss, by Pat Verducci. It’s the only movie she made, and I wish she’d made more because it’s fucking brilliant. […] Watching that movie gave me a realization, which I love because people say art doesn’t change minds, but it does.

There’s also an art film, Aimy in a Cage, an adaptation of the graphic novel Aimy Micry by Hooroo Jackson, about a horrible male gold digger. In the story, the way that the man interacts with not only the grandma, who he’s catfishing, but also her grandchild, to whom he’s the only person who’s ever been nice to her even though he’s a bad person, really makes you appreciate that the main character only has violent men to choose from. The only people in her life who will have sex with her or that she will want to have sex with are either violent men or people who would be inappropriate, like a student. Without saying it, the movie makes the point that it’s that or nothing – like, if you want to have sex and romance, sometimes, the only choice is to risk a bad man or have nothing.

I have a long-term partner and am secure and comfortable, but it made me realize, before that, in all interactions with men who seemed like they might be interested, I always chose nothing as a protective choice. The victim blaming is so internalized that I always assume that if I don’t scare people off to make myself safe, anything they do to me will somehow be my fault because I didn’t bother to chase them off. That’s been debilitating. Even though I have a long-term partner, and we love each other, I felt I needed to pretend I didn’t like him as much as I did. When we were first getting together, I wasn’t honest about liking him and held off on physical affection longer than I innately wanted to because, philosophically or socially, the mind thing was saying, “No, you have to protect it.” But, if you hold off and protect it, you can’t fully enjoy your life, and that’s a huge bummer because enjoying a full life is nice.

When I was younger, the hot boys I wanted were so clearly almost dangerous that it felt too dangerous for me to let them in at all or to let them see that I liked them in any way. If I did, they would have the chance to say that it was my fault if they did something. Every time I talk about this, it sounds so obvious and basic, but the idea that you’re the only person who has the ultimate responsibility to keep yourself safe from men who want to do anything they possibly can do to you is so deeply buried that it’s a total mindfuck.

I don’t know the extent I’ve talked about this, but I did have stalkers – two boys in my class – when I was eight years old. We moved, and they were in my new school. They were like, “We fancy her and are going to follow her around all the time and stare at her when she’s in the garden and be weird and make it uncomfortable,” which I didn’t enjoy. There was definitely a vibe that if I did anything to show that I didn’t completely hate them all the time, it would be like I was saying it was okay. No adult ever put off that idea, which was not good for me. But I don’t feel like that isolates me. Many people have had worse individual and immediate experiences than I have, but plenty of people have had pretty much the same.

So, technically, it’s a personal story, but it’s personal in a political way.

Kaplan: I remember when something bad happened to me, I was told not to prosecute because I would be blamed in the media — that’s exactly what you’re speaking to.

Napier: Yeah, they trick us into actually genuinely believing that we are the last line of defense for ourselves. They set an impossible expectation of self-safety, and it fucking sucks.

Kaplan: For example, your comic has a line about the woman’s dress being too short, and that’s a real experience for women in sexual assault and rape cases, you know?

Napier: That’s personal. I’m 35 years old and only started wearing things I genuinely want to wear since the pandemic began because I’ve been sheltering essentially the whole time. I can wear whatever I like because I know that no one will touch me. After all, there’s no one in my house except my partner, whom I want to touch me. I wouldn’t wear certain things with no bra because if someone touched me, I would feel like I made them. I shouldn’t feel that, but some part of me does, and I don’t like it.

Kaplan: In US high schools, I remember how my friends with big boobs couldn’t wear spaghetti straps. I was a dancer, so I was developmentally delayed and could always wear tank tops — no one said anything. But it always bothered me that the dress code was inconsistent.

Napier: Genuinely, not being not feeling like you can wear what you choose is ruinous. It sounds like a surface issue, and many people will say, “Oh, never mind, it’s just clothes,” but clothes are more psychologically vital than most people are willing to admit. Clothes are a part of gender euphoria, and that applies to cisgender people as well as trans people. Then, they affect the experience that our body has physically because they touch our body, and they make it appropriate or not appropriate in terms of what we were talking about above, like, if you’re swimming, you need a swimming costume that is the right fabric for the activity. However, the outfit that might be right for the senses of the individual is not allowed to be the first outfit that’s on the slate because of how that will cause other people to respond, and that is not regulated.

Kaplan: Can you tell me more about the dedication page?

Napier: Its vibes. I was playing Alice Cooper’s “Poison” a lot when I was in the early stages of this comic because it’s the story of the song, essentially, but a girl version. In the song, Cooper sings about how very sexy this dangerous person is to him, and I was like, “Wait a minute, [women] get that, and then we’re told that we’re stupid for that and that makes our abuse our fault.” I’m not quarreling with Cooper here; it’s a hot song. However, I wanted to have a piece, you know?

Then, Jim Steinman is the guy who wrote the Meat Loaf songs, and I feel like the vibes are right. I feel like I got what he was doing. He’s dead, so he won’t get to read this comic, but I think he would have understood it. I hope so, anyway.

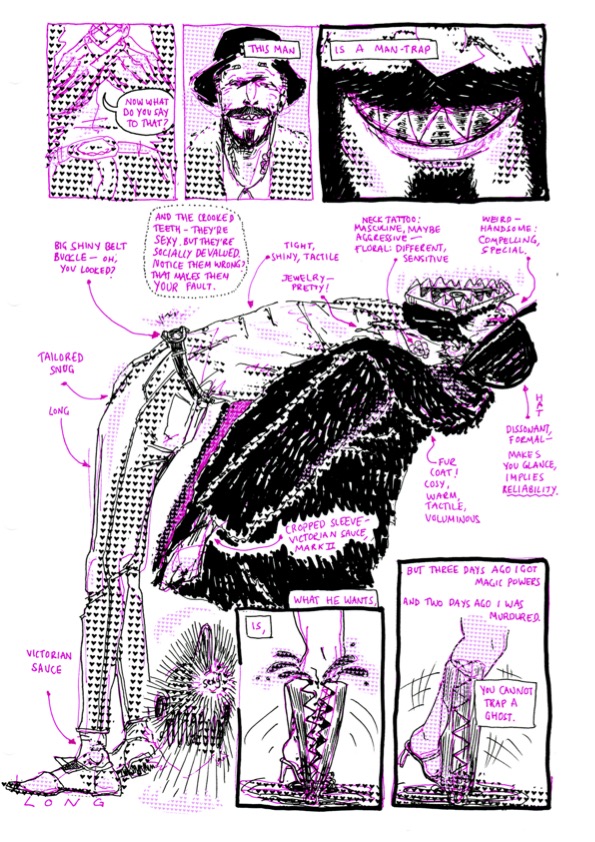

Finally, for that guy from Jamiroquai. There’s a pickup artist, whose name I don’t remember, but he made peacocking a thing, and he would teach the incels – although we didn’t call them incels yet because he’s from a few years ago – to use a piece of clothing to catch the eye [of a woman], and then capitalize on that. He wore a big hat that reminded me of what the guy from Jamiroquai used to wear, and I had a massive crush on him and liked the hat. So, the pickup artist choosing that specific clothing item to prey on girls felt personal, like a psychic attack on me, because if he had met me wearing that hat, he would have used it to get in and do something horrible. That’s his MO, and that’s offensive that we should suffer just because we think someone looks nice. Looking at a guy in an outfit and thinking it’s cool is not me saying, please fucking rape me. So it felt important to me to stay true to my younger self and say, “You can’t ruin [the hat] by being a creep. I can be into the stupid hat.”

Kaplan: What’s behind your decision to accent the page with hot pink?

Napier: Well, the hot pink — I had a pink pen. I like pens with colored ink. It’s one of the girlish fancies that I retain to this day. Also, I wrote about the harlequin manga quite a few years ago. The harlequin romance novels in America are called ‘Mills & Boon’ in England. In Japan, they have been adapted and translated into manga for decades, and you can get tons of these machine-translated mangas through Kindle. Then, someone printed volumes of those translated into English in the 2000s, and I found a couple while I was on a trip to Cardiff. They were printed in colored ink, with a pink and violet range, which looks nice. The pink range was cuter, and the violet range was the one with the really fucked up stuff.

As for the hearts, the story is about romance and the idea of being loved. The whole machine of heterosexuality comes pre-applied with hearts, right? And they’re another thing that rolls into the gender at large. I abandoned the urge to draw hearts on things very early because being girly felt either directly or indirectly unsafe. Sometimes the image felt unsafe because if you draw hearts on stuff, you’re silly, and people won’t take you seriously. So it’s the reclamation of cuteness but also a subversion.

Kaplan: Why did you decide to crowdfund with Zoop?

Napier: I was tweeting about the project, and they messaged me, “Do you want to fund it with us?” At first, I said, “No, that’s too much pressure.” But then, I thought that’s silly because that’s just fear. Why not try? What’s the worst that can happen? The worst that can happen is nothing because if it doesn’t fund, it obviously will, but if it doesn’t, then I’ve invested no money. And so what? They might not want to work with me again, but also, evidently, I wouldn’t have something people wanted.

Kaplan: I’ve heard from other creators, like Paul Allor, whose comic you edited, that Zoop pushed them to make decisions they wouldn’t have made independently. Did you find you had a similar working relationship with Zoop?

Napier: Honestly, it took me a long time to agree. I was concerned they wouldn’t want to print all of the cocks. So I said, “It’s fine. You won’t want to print all these cocks, and they said, ‘Send us the cocks. We’ll see if that’s fine or not.'” So then, I felt really, really, really shy. I didn’t want to send them the cocks because it felt embarrassing, so I left the project for a month, and they DMed me again, “Are you going to send us the cocks?” Eventually, I steeled myself and sent them the second to second largest cock in the book, like, will this be fine? They said as long as it’s not on the cover, so I agreed. And ever since then, my experience has been essentially supportive. I have nothing bad to say.

The Magic Necklace is currently crowdfunding on Zoop.