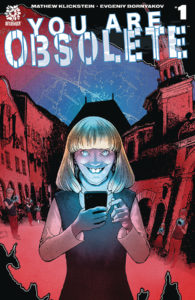

That book, published by AfterShock Comics, follows a disgraced journalist (some kind of controversial statement she made possibly taken out of context), as she journeys to a mysterious and isolated island in Europe. Our intrepid reporter is essentially confronted with a small town under the grip of some sort of sinister cabal of children, who are killing adults by their 40th birthdays.

It’s an interesting mystery, illustrated with eerie kineticism by the artist team of Evgeniy Bornyakov, colorist Lauren Affe, and letterer Simon Bowland…all with a chilling first cover by the great Andy Clarke. The Beat recently had an opportunity to send some questions to Mathew Klickstein, asking about his switch to comics, influences, and, of course, You Are Obsolete.

Check out his answers below…

The Beat: So, because you’re someone who’s transitioning from another medium (in this case film) to comics, I feel almost obligated to ask…what has that been like for you as a writer?

Mathew Klickstein: It’s true that I am a complete novice in the comics realm. I started off with film/television, journalism, theater and my series of pop culture history books on nostalgic subjects such as “Old School” Nickelodeon and The Simpsons. Having successfully navigated these various other mediums already, as well as the nationwide travels I’ve taken while working on my various projects over the years, I’m well aware that each medium is really its own “subculture” and fiefdom with its own hierarchies, shibboleths and aesthetics. So, I’m extremely grateful how welcomed I’ve already been into the comics community through the fine people at AfterShock and the artists they’ve brought on to work on my series, as well as the gracious readers/fans/reviewers who have been so generous in not only their praise of the book (at least Issue #1!) but also their very specific understanding of what I did and have been trying to accomplish with said series. Some of the analysis has been startlingly apt, and I haven’t really experienced this kind of thing in the other mediums I’ve worked in over the past two decades. Maybe I should’ve been in comics all along!

I’m not sure if this answers the question that well, but to be more specific, because of my extensive background in film — both as practitioner and historian/critic — I incorporated a lot of that form’s aesthetic qualities into You Are Obsolete. The book evidently works because I can craft nuanced character/story development courtesy my experience in other mediums, and yet when I approached You Are Obsolete, I wasn’t familiar with the form of comics … And this combination seems to have led to a book folks are really enjoying.

I’ll add that I love collaborating on projects, and film/TV/theater is as collaborative as you can get in the arts field. I’ve written a few screenplays with friends in the past, and it’s almost always a pleasurable experience for both parties, resulting in content we’re proud of and that sometimes finds itself into production. But … when you write a screenplay, it’s such a relatively lengthy, arduous process of going from page to the screen. When I’m writing an article for a magazine or a book — which can, all told, take two or three years from conception to on-shelf sale — it’s an extremely solitary, laborious and time-consuming process with little results right away (if at all, in the case something doesn’t get published, produced or sold that I might work on, which of course is the risk we all must take in the creative/media field).

With the comic, though, the liberation I felt, the speed I was able to work at, the fact I could write up every single detail of every single panel to my very subjective personal specifications without any interference except for almost-always helpful notes from my editors Christina Harrington and Mike Marts made for a remarkable creative experience. It was as though I was finally allowed to let my engine run as strong as it wants, and there were no speed bumps or curves or unpredictable distractions in the way. I could just go, and suddenly a few days later, I would see these astonishing pieces of art by our artists that weirdly matched exactly what I was considering when writing everything down in the script.

There’s no question Evgeniy Bornyakov, for instance, is an absolute genius. But what a lot of the readers and reviewers may not know is how uncannily fast he is at his work. I might see something he did that is already mind-blowing but may need one or two little changes, and almost within a few minutes I sometimes get the panel back, and it’s just as mind-blowing but also tweaked accordingly as though I snapped my fingers and some kind of “creativity machine” made it so. You don’t get that kind of immediate feedback/results/dividends in film/TV/theater or journalism or traditional books. It’s very satisfying, especially to someone like me who can’t stop writing, producing and creating to the annoyance of my wife, friends and family who are never able to shut me up about ideas I have brewing. I may have finally found a medium that can keep up with me, and — at the ripe old age of 38 — that’s nice to discover!

The Beat: What drew you to comics as a medium versus continuing to work within film?

Mathew Klickstein: I may have answered a little of that in response to the previous question, but yes, the process of creating a comic seems to move a lot faster and easier than film/TV. Obviously, the process for producing film and TV (and, for the most part, traditional books) moves so slow from conception to presentation. With comics, it seems, I can come up with an idea, sell it to a company like AfterShock, I’m writing the scripts, the art’s getting made to perfection, and BOOM — six months later — it’s on the shelves. It’s a very rewarding process for those of us who spend most of our creative career on hundreds of pages of proposals, rewrites, and projects that may either never go anywhere or that won’t make it to the eyes/ears of audiences until years later. That process is, of course, rewarding in its own way too — otherwise I wouldn’t keep doing it, and I love writing and producing film/TV. But, I’m enjoying this quick-fix instantaneous reward for my work that is otherwise so rare in the creative/media realms these days.

Also, movies and TV (and books) cost tens/hundreds of thousands of dollars from soup to nuts (if not, of course, much-much-much more in the case of bigger films, though I typically work in reality TV and documentary, since these too are so much easier and cheaper than feature films). Comics are much quicker and cheaper to produce than film/TV/traditional books. It’s nearly impossible to get your script sold or made or your traditional book sold and published, especially these days when there’s so much more competition than ever before and so few risk-taking visionaries on the executive/financial side than ever before, too.

The truth is, the original concept of You Are Obsolete was in fact a film. I had written up a three-page synopsis told from the perspective of the main character Lyla Wilton, which just flowed out of me after a drunken ramble with a few friends who were talking about the concept of a “killer video game” with me. I ran with the idea, wrote the aforementioned synopsis and began passing it around to the usual channels as a movie. Folks seemed to like the idea a lot, but there was nothing concrete happening, and after about a year, I took the advice of a few friends in the comics world who suggested I try to sell it as a comic book series. I gave it a shot and almost instantly AfterShock took it. They were my first call. It was that “easy.” No bureaucratic rigmarole, no dealing with grossly elaborate financial concerns, no slowdowns with the many, many other distractions that take virtually “forever” in the realm of traditional publishing, journalism and especially film/TV today.

I know I’m still so very new here and therefore may be naive to the brutal realities of all of this, but in my experience so far, it appears the realm of the comic book is the truest, most pure commercial art form on the scene right now. You come up with an idea, you sell it, you work with the artists on something great to your exact specifications, and the thing is out a few months later for audiences to read and analyze. That’s amazing. I don’t get that undiluted directness elsewhere.

The Beat: I really liked the first issue of You Are Obsolete, basically from the title onward it plays on this very real fear most of us have about being left behind by a changing world. How much was the idea for this story informed by your own fears? And are there any specific experiences you’ve had that motivated you to write it?

Mathew Klickstein: Thank you for so saying, and we are receiving a lot of the same comments about how eerie and “creepy” the book seems to be so far. I really hope this response continues. I was profoundly influenced by The Twilight Zone throughout the course of my life, and so it has of course had a great impact on the inspiration for You Are Obsolete. This is particularly true regarding the book’s tone and style, which I’m delighted has been compared to David Lynch’s Twin Peaks, as well (another obvious influence on You Are Obsolete, particularly the more playful and absurdist moments … which I’ll now tease get more pronounced throughout the series!).

Ever since I was a kid, I typically hung around people who were much older than I. I was almost always the “baby” in the group. All of my first girlfriends in high school, college and post-college were a few years older than I (and also tended to hang out with much older people, meaning I was with my girlfriends and a lot of dudes and ladies who were ten or twenty years older than I). In film school, I didn’t really connect with the kids in my undergraduate class, but I connected almost right away and very intensely with my school’s grad students, some of whom were a decade or more my senior. I also tend to work and collaborate with people much older than I. Because I watch mostly “old” movies and TV shows, read almost no contemporary novels and listen to almost no contemporary music, I end up being the guy at the dinner or other meet-up who is hanging with Grandpa in the corner, talking about the Marx Bros, John Coltrane and Green Acres.

All of this to say: in my personal and professional life, I tend to be the youngest guy in the room. So, the idea that I would then put together a comic book series about how the kids are killing off the older people with digital technology is less about any fears I may or may not have about being eclipsed by the next generation (since I usually am the “next generation” in the groups I travel in) and more about my profound fears about technology itself. What can I say? Again, I grew up with The Twilight Zone, whose 160 episodes are almost exclusively about fears of technology running amuck in the future. I also read a lot of George Orwell and Aldous Huxley at a very early age, along with the likes of Ray Bradbury, Harlan Ellison and Philip K. Dick, folks who didn’t exactly paint the brightest picture of future technology. As I got older, I got into the likes of Nicholas Carr, and books like Astra Taylor’s The People’s Platform and Evgeny Morozov’s To Save Everything, Click Here and the many, many works of Slavoj Žižek (a hero of mine whom I reference both indirectly and directly throughout my series).

What can I say? I was a techie kid who programmed his own video games with “If … Then … Else” statements and took some programming classes at school and enjoyed reading Wired and Odyssey (for kids) and Popular Mechanics etc. But, as I got older, it just seemed more and more like something was approaching a little too similar to the sci-fi stuff I had been reading. When my friends and I all went to college, a few went to top STEM schools like MIT and Stanford where they majored in crazy things like “cognitive sciences,” basically spending their time on early AI formulations and whatnot. And it got scary talking with them, understanding more and more from the back end how quickly things in this arena were progressing without much mainstream transparency.

Even in the most recent last few weeks, we are privy to more and more revelations about how Silicon Valley operates, how these corporations running things are really working along with all this, the technology itself affecting our brains, our children (hint hint) and so on. Look at all these Silicon Valley folks coming out against this technology now — sometimes the very tech they created themselves! How they don’t let their own kids use tablets and whatnot. A few of my friends are still very involved in that world and now newer developments like Bitcoin/Blockchain etc., and they often poke fun at my neurotic, paranoiac “luddite” sensibilities here. But whenever we really get into talking about these issues, as adamant as they are about their perspective, I can once in a while observe a worried look on occasion that reads as, “Shit, what if he’s right?!”

I could go on and on, but then this article will change dramatically into a whole other thing, so let’s just leave it at the fact I’m not personally afraid of generational shifts — it’s part of the game and again I still tend to be the “kid” in most situations even at my age. But I am quite concerned about what’s going on with technology, especially digital technology and the internet ecosystem right now. At the same time, I’m quite fascinated by it, have a number of friends and colleagues who work in this arena whose brains I love picking, and I wanted to capture this very special time and place we’re in right now with our culture, translating all of these themes into what I hope to be an engaging tale of terror.

I wanted my comic book series to have a familiar base (okay, the “bad kid” trope we’ve seen before — Children of the Corn, Village of the Damned, The Omen, etc.) with a contemporary to-the-moment twist (okay, the growing fear of the dangers technology has been bringing to the fore over the past decade or so).

The Beat: Let’s talk a little bit about the horror trappings here. In the marketing for the book, it’s been tied to “the eerie naturalism of the 1970s.” Can you elaborate on that?

Mathew Klickstein: I absolutely love the movies, especially horror films, from the 1970s and early 1980s. There was such a spectacular freshness mixed with grittiness exhibited in those pictures, such a level of uninhibited artistic expression that we rarely get to see much of after the late 1980s in film. It’s been extremely refreshing and rewarding to see how many reviewers (and hear from so many readers) make an immediate connection between You Are Obsolete and and these fantastic cinematic works that so profoundly influenced the style/tone of You Are Obsolete: The Wicker Man, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Carnival of Souls (1962, but close enough!), The Stepford Wives, Videodrome, Jacob’s Ladder, In the Mouth of Madness, Village of the Damned and other films by the masters of this genre like John Carpenter, David Lynch and David Cronenberg.

Really, what we’re talking about here is the kind of bleak and gruesome naturalism of these films that were really mirroring what was going on otherwise in the most beloved films at the time during the so-called New Wave of American Cinema (think easy ones like Easy Rider and the films of: Hal Ashby, Scorsese, Coppola, Elaine May, Mike Nichols, et al) that echoed that of the German New Wave (Wim Wenders, Werner Herzog, RW Fassbinder, Volker Schlöndorff, et al). “Real” people dealing with “real” problems and “real” emotions outside of just the “I vant to suck yer blaaaahhhhd!” monster movies of the 1950s/60s that came right before (and which I also love, but for different reasons) or the slasher/jump-scare/mutants/

This “real” fear in You Are Obsolete is more like those films of the 1970s and early 1980s, or The Twilight Zone or, today, the best episodes of Black Mirror along with recent films like Midsommar and

My nutbar friends at Troma put out this absolutely zany and extremely grim film in 1986 called Combat Shock (aka American Nightmares), and it could scare the shit out of anyone watching it no matter how tough (John Waters claims it’s the only movie that has ever made him throw up). And you know what? It’s the most basic, simplistic story and idea for a film you could think up. Almost nothing “happens” in a horror/thriller/sci-fi or even action sense. But the way the characters are developed, the way the “story” (what that there is) moves forward and particularly the graphic details of the “protagonist’s” (?) horrific day-to-day existence come together makes for one of the scariest movie-going experiences ever offered in this country or anywhere else.

We’re talking here about tone, ambiance and background detail (both physiognomically and internally). We’re talking HP Lovecraft and Edgar Allan Poe. It’s the emotionality evoked while you’re reading. The hidden underbelly stuff. That’s 1970s/1980s horror, and that’s what I dearly hope I achieved with You Are Obsolete.

The Beat: In mystery thrillers like this one, I’m always interested in the rate of revelation. How did you decide how much to reveal to orient the reader, and how much to hold back to build your mystery?

Mathew Klickstein: That’s an incredibly astute question, and I thank you for asking. One of the few times I had a dispute with my editors over the book was how I was choosing to deal with the passing of time and pacing in the story, which took some amicable compromising to get right. This may be due to my, again, naivety re: the form and aesthetics of “proper” comic book writing/production. And/or it may be due (I believe moreso) to my aforementioned love of slow-burn horror/thriller films from an earlier era.

I’ll add that the bulk of experience I’ve had with comics up to this point in my life is mainly the undergrounds, especially those of the 1960s-1990s — Robert & Aline Crumb, Ivan Brunetti, Johnny Ryan with whom I’ve had the distinct pleasure of working with on a traditional book recently, the Weirdo and Punk folks like Peter Bagge and John Holmstrom, Phoebe Gloeckner, Daniel Clowes and my friend Shannon Wheeler. And so, having learned about the down-and-dirty form from these innovators whose work I love and whose interviews I read obsessively (or in the case of Wheeler and Ryan, with whom I consult with when appropriate), I suppose it’s no wonder You Are Obsolete has a slower, more meditative pacing in which seemingly “banal” moments can be blown up into whole pages of detail and existential consideration just as we see so often in these aforementioned underground comix. That goes again back to the Lovecraft/Poe (and, I suppose, Kafka) style of storytelling when it comes to suspense, sinister backdrops and a generally more “gothic” feel overall that works so well in the mystery/sci-fi/thriller genre when given the chance.

I’m thrilled the AfterShock people were ultimately cool with my messing around with time as I do (and, again, this is something that becomes more intensive as the story progresses and we learn more about Lyla’s background, more about what’s happening with the children and so forth…). Yes, the slower pacing and drawing out of expectations may not be everyone’s cup of tea, but it seems to be one of the elements of Issue 1 at least that readers are really connecting with, so hopefully they’ll be down for more of this kind of thing and the captivating, seductive aspect of the storytelling I hope I accomplished with the rest of the series.

My goal is to put the reader on a trip, to take her or him away to another place for a brief period, altering his perception not only of place but of time itself. That may seem lofty, but it seems to be working so far. If folks will stay on for the ride (especially when things get really funhouse-wacky in Issue 4), I’ll have done my job as captain of this B Traven-esque “death ship.”