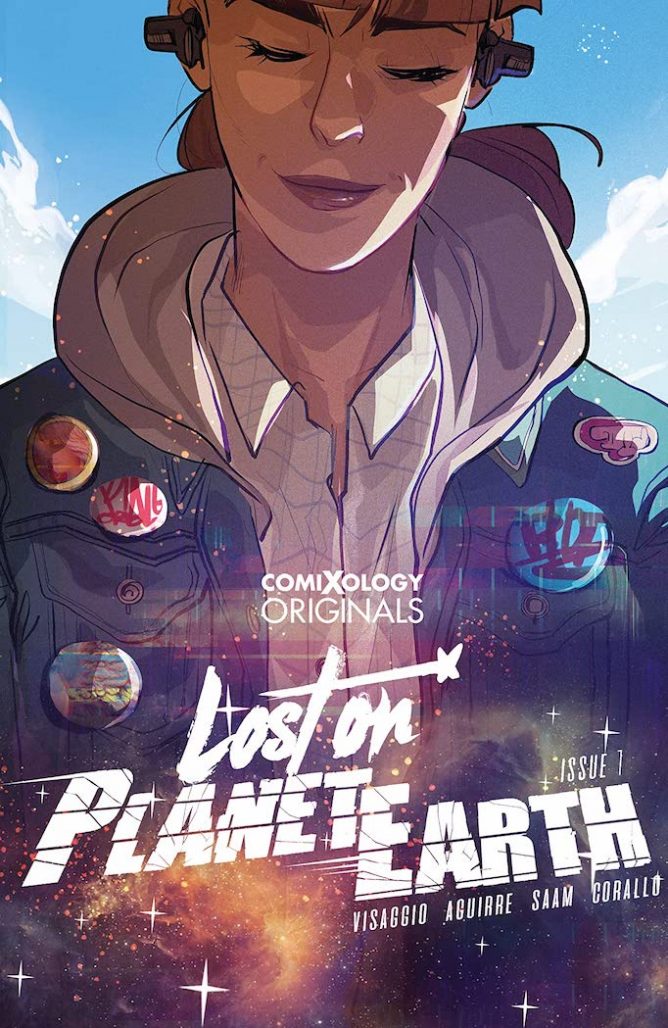

Though Magdalene Visaggio and Claudia Aguirre’s ComiXology Originals miniseries Lost on Planet Earth takes place in a sci-fi setting resembling the world of Star Trek, at its core is a very human, relatable story. In the series, protagonist Basil finds herself at a crossroads between the life she planned for and the life she wants. She learns that the world isn’t as simple as she once believed and begins to understand the price of a “utopian” society. Magdalene brings her love of Star Trek to the book but isn’t afraid to be critical of the franchise, exploring where it falls short through the lens of Basil.

I had a great time chatting with her about the development of the series, building worlds, collaborating with Claudia, and how the series unexpectedly reflected her own life experiences.

This interview was edited for clarity.

Matt O’Keefe: I really enjoyed the first two issues of Lost on Planet Earth.

Magdalene Visaggio: Thank you. Claudia and I are very proud of it. Things have changed along the way. We had a plan, but it evolved a lot over time. After Issue 2, I’m just following Basil where she’s going.

O’Keefe: Basil’s story feels very open-ended after the 2nd issue, like she could go in any direction following this turning point in her life.

Visaggio: I didn’t know what was coming. I wrote Issue 3 and when it got to issue 4 I realized the original plan no longer worked, especially in light of developments from previous issues, so we figured it out as we went. It was very emotionally exciting to have that happen.

O’Keefe: Will the story still cover the assimilation plot set up in the first 2 issues?

Visaggio: That’s where the book was originally going. I wrote 3 issues of one version of the story and 2 issues of another version, but it felt very heavy-handed, very preachy. I wanted to make sure the story developed in a very human, emotional way.

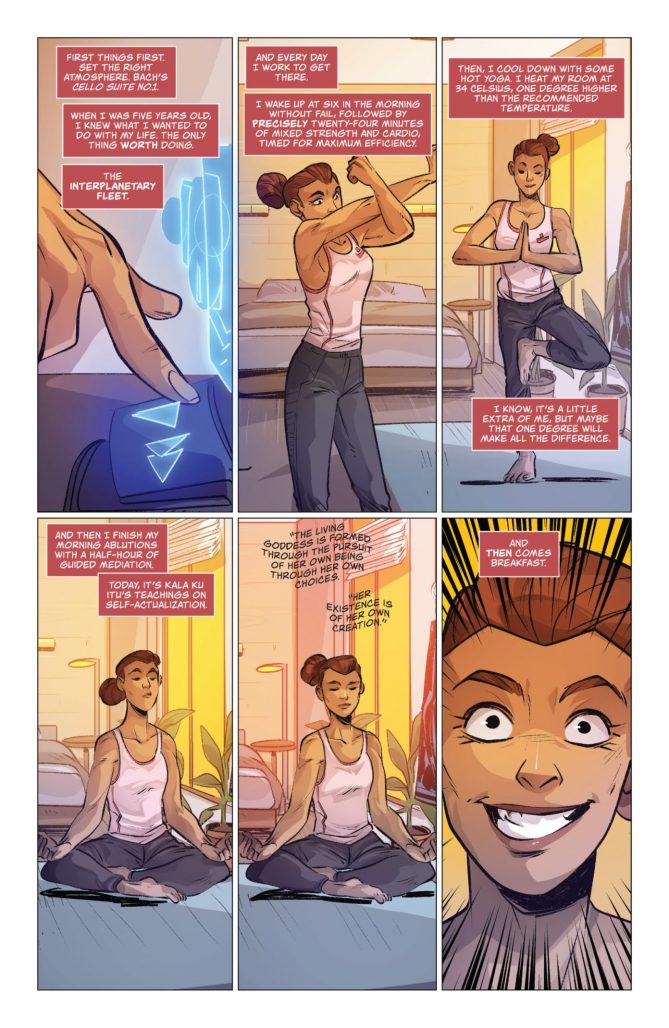

O’Keefe: One thing I really loved was how Baze came to her realization while listening to philosophy. That was a really clever way to show an internal change, which normally can’t be conveyed in comics without narration.

Visaggio: I knew I wanted to find a way to externalize an internal change. The philosophical element came when I was in the middle of writing the exam scene [where Basil runs out during the test]. I needed to have Basil break, and it wasn’t landing. I reread what I had already written and that’s when I really centered in on this one throwaway line about an “8th century Baylor Sage Kala Ku Itsu” and I got really fascinated with the character.

She was very much influenced by my background in Catholic theology, specifically my readings of Saint Teresa of Ávila and Thomas Merton. Both of them articulated this philosophy of deliberateness and acceptance and a sort of self-possession.

O’Keefe: Sort of like living in the moment?

Visaggio: Not quite living in the moment but living in the present, which I think is something different. I think of living in the present as being grounded in the world you have and making deliberate choices within it.

I decided to thread the philosophy of Kala Ku Itsu throughout the first issue and what I found is that this ancient philosopher becomes this big guiding thread throughout the whole story. I believe there are references to her in every issue

O’Keefe: Are all the philosophers mentioned in the series fictional?

Visaggio: Yeah. Kala Ku Itsu is a name I made up that sounded vaguely Romulan. I don’t know what the hell a Baylor Sage is, it just sounded real enough, you know? I spend a lot of time on names so none of the aliens or planets mentioned feel generic. As a result, sometimes you come up with really interesting characters about meaning to.

O’Keefe: I think one of the hidden benefits of world-building is, even if you don’t dive deep into a place’s history, the world feels richer.

Visaggio: I found as a writer that I would get so caught up in world-building and internal consistency that it would paralyze me. It got to the point that I couldn’t write the story because I needed to have an absolutely airtight universe. Now I treat worldbuilding as set dressing. I want the reader to feel like there’s something behind everything the story encounters, even when there isn’t.

O’Keefe: Was Claudia always attached to the project?

Visaggio: Yeah. I love Claudia. We developed this book together because we wanted to work together again and we’re not sure when [their Black mask Studios series] Kim & Kim is coming back. We’re a really good team. It’s a very strong creative relationship. We call each other comics wives.

O’Keefe: She puts so much emotion and expression into her work with every character she draws, but she also really nails the utopian sci-fi aesthetic.

Visaggio: Yeah, she’s very versatile. I love everything she does.

O’Keefe: Do you feel like you’re wrestling with your feelings on Star Trek through the series?

Visaggio: I don’t wrestle with my feelings about Star Trek. I love Star Trek. I can’t not love it. And I acknowledge that it’s got some problems. The stuff I obliquely bring into the book is weird elements that emerged because [the original writers] didn’t think everything through when developing the series.

In Star Trek, the viewer is on the Federation’s side. The Federation says one day we want the whole universe to join the one big, peaceful government. We accepted that even though we live in a country that’s absorbed societies into itself over time, often in degrading and violent ways that we just kind of all agreed not to think about.

I think that critics of Star Trek and the Federation, in particular, are spot on. One of the series’ blind spots is how the Federation assimilates other societies and viewers are just supposed to accept that. I think it was Garak who remarked that at least the Borg tells you what’s coming.

O’Keefe: I sometimes wonder if writing any utopian world is inherently problematic because it has to simplify things to the point of kind of ignoring the problems of society no writer knows how to fix.

Visaggio: Yeah. In fiction, there’s no way you can construct a perfect society. The Federation was very lazily constructed from a story perspective. I don’t mean that as a criticism, that’s just the truth. It’s this hodgepodge of things, essentially a more expansive version of the United Nations that’s inherently good.

The reason the series is so human-centric is that it’s expensive to make aliens. The reason the government is located on earth is that it’s somewhere viewers know and can identify with. We have an emotional connection to Paris and San Francisco that we’ll never have to some city on Vulcan.

Star Trek hasn’t spent a lot of time questioning itself. When it does, things become very messy in a way I really like. That’s one of the reasons I love DS9, Discovery, and Picard. They look at the seams in the construction that don’t fit., that don’t quite match what we want them to be. I think that’s really compelling.

I know so many people who love Star Trek because of the core message that humanity has grown. I don’t love it for that reason. I love Star Trek because I think it’s fun television and the overall picture it paints of a future where we’re still trying.

Star Trek loves to say that humanity’s evolved but the stories show us that it ultimately hasn’t. I wanted to write a story that existed in that space and I figured there’s not a chance in hell I’m ever going to get to do that with the Star Trek property. I would never have the freedom to be critical the way I wanted while working on a licensed property.

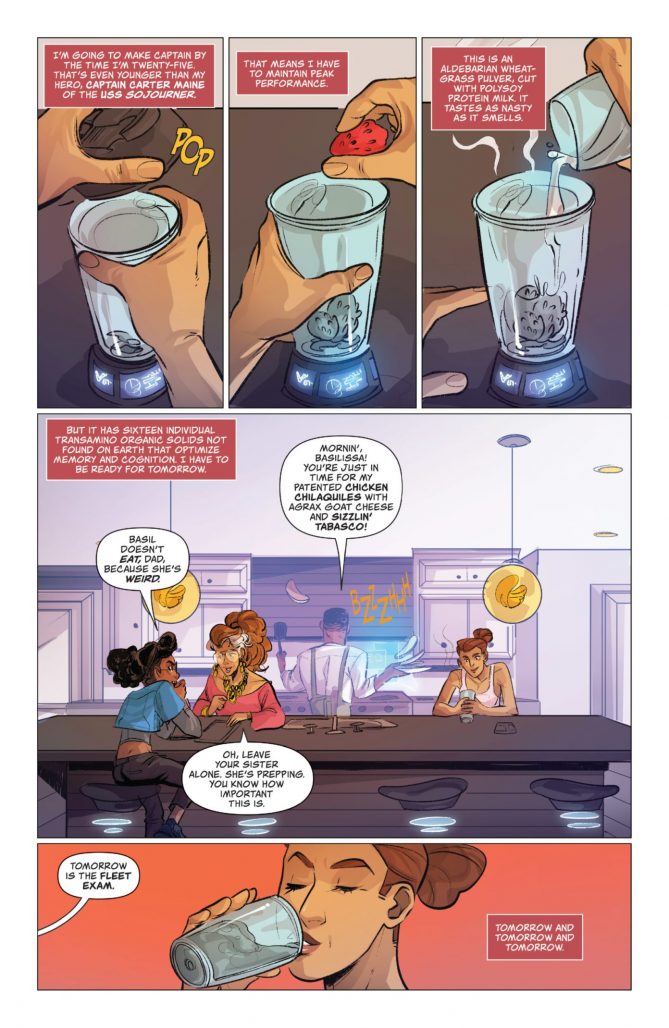

Lost on Planet Earth really started with my [feelings about] Wesley Crusher. At the very beginning of Star Trek: The Next Generation he’s supposed to be the Mozart of Mathematics and Physics and then he just kind of becomes the ship’s navigator. He goes off to Starfleet Academy and trains to be a pilot.

It’s like, what the fuck happened? […] At the end of the series, they decided to wrap up his arc by having him come to the realization that he was going down his father’s path instead of figuring out who he was. It’s the first time we see someone really questioning the decision to go into Starfleet. You just assume that everyone grows up to join Starfleet, take orders, and fly around space.

O’Keefe: It’s like the family business, but it encompasses the whole world.

Visaggio: Yeah. We only see glimpses of the people who don’t follow that path. Like, I don’t think that everyone joins Starfleet in Star Trek, but that’s all we ever really see because it’s a show that’s focused on Starfleet and its officers, who believe in its mission. So of course, that’s the perspective of the series.

I decided to create a society in Lost on Planet Earth where that level of implied militarization was explicit.

The price of world peace, the price of ending the cycle of violence that has consumed humanity, is everyone has to get on board with the mission. That creates a very regimented, very ideological society based on this vision of the common good that requires you to subordinate yourself to the state as the representative of the civilization for a minimum period of service.

In exchange, you don’t have to worry about money. After serving, citizens get to use the rest of their lives doing whatever they want, because they were on board with the mission and have done their time. Baz is somebody who never thought critically about her place in the world and suddenly found herself doing so.

O’Keefe: The cost of not being part of the fleet is basically being handed the present-day challenges where you have to survive through the economy. That’s a really interesting angle.

Visaggio: I think about the economics of Star Trek a lot and how they could work. I can think of a number of ways they would. A post-scarcity society seems like a powerful motivator to get people on board with the mission and do their service. But people who don’t get on board are basically relegated to poverty. To me, that feels like an amplification of American capitalism. You’re either on board with it and give yourself over to our economic and political philosophy, or you’re not. If you are, you can thrive. The message we internalize and hear from a very young age is if you don’t get a good job and work hard, you don’t deserve to live.

O’Keefe: I really like how Lost on Planet Earth reflects our time without trying to preach. It extrapolates the struggles of our time into a possible future.

Visaggio: If it’s doing that, it’s in the service of Basil’s story. It’s constructed from the question of what you do you opt-out of the thing you’ve been preparing for your whole life at the last second,

I didn’t realize that this story was closely tied to my own life until the first issue was already out in the world. Reading a review but it clicked for me that the story reflects my experience in Roman Catholicism and my decision to abandon any call into ministry.

O’Keefe: A moment that really hit me was at the end of the second issue when Basil’s dealing with the fallout with her family over the decision she makes. Her friend becomes frustrated with her when Basil is already so overwhelmed. It shows how changing the course of your life is so demanding on all fronts.

Visaggio: Velda knows what Basil is dealing with and the life that Velda has to lead as a result of where she lives because the society is so militant, so homogenized. […] These little vectors of oppression are hitting Basil that she never sorted out because she’s never really let herself think about who she is. Thinking about who she is would get in the way of what she wants to do. She knows that it would cut her off from the path that she feels obligated to go down.

So you have Velda at the end feeling like, “Okay, look, it’s not my job to tell you about yourself, but you need to wonder why you even brought Ethne up. Because nobody was talking about her.”

O’Keefe: I guess I wanted her to be there as a shoulder for Basil to cry on.

Visaggio: That’s not Velda. Velda is a bitter, young punk. She’s extremely political. She tries to get along with people, but she’s not good at being emotionally open, and you see that repeatedly [throughout the series.]

O’Keefe: Yeah, I can definitely see that, and I think it goes to show the depth of the character you’ve already established in just two issues. How has your experience been working with ComiXology?

Visaggio: Very positive. They just kind of stay out of my way and let me do the work that I want to do because Comixology trusts me as a creator

O’Keefe: And Lost on Planet Earth is a five-issue miniseries?

Visaggio: Yeah.

O’Keefe: Is there any chance there will be more?

Visaggio: Lost on Planet Earth is specifically Basil’s experience in this world. We’ve discussed a follow-up story, but it would be very different, with a different main character. The story would come out of how this series ends, so I can’t say anything more than that. While making the book Claudia and I really fell in love with a character who shows up in the last few pages of the last issue, who we think has a very interesting story.

O’Keefe: I hope to see that come to fruition! Thank you so much for talking with me.

Visaggio: No problem, thank you for having me!

Follow Magdalene on Twitter @MagsVisaggs. The third issue of Lost on Planet Earth releases tomorrow, June 16.