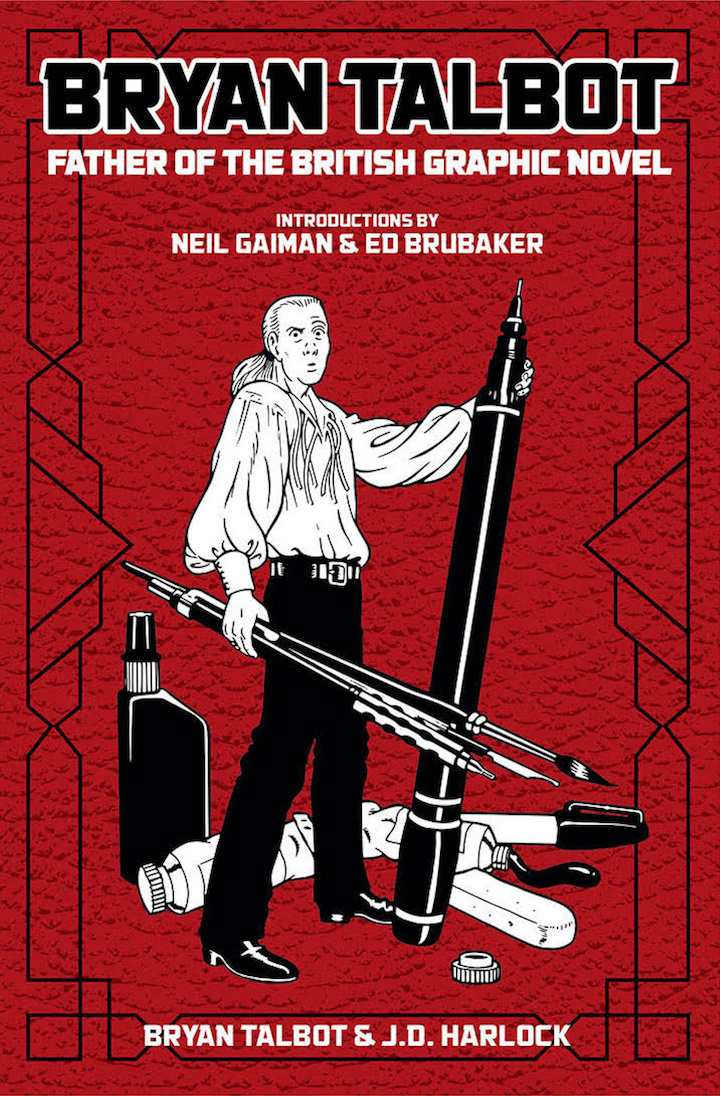

Bryan Talbot is one of the UK’s most respected comics artists. A member of the “Brit Pack,” a group of influential British comics creators that included Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Grant Morrison, his work has significantly impacted the North American comics industry. He has contributed to Future Shocks, Judge Dredd, Nemesis the Warlock, Ro-Busters, and Sláine in the Galaxy’s Greatest Comic and is renowned for his body of graphic novel work, which includes The Adventures of Luther Arkwright, Heart of Empire, The Tale of One Bad Rat, and Alice in Sunderland.

Talbot’s latest project is an illustrated biographical novel that will detail Talbot’s career and work and include never before heard stories of his time in the comics industry. “From his time working with DC Comics to industry events and some landmark happenings, you don’t want to miss these tales from behind the pages,” reads the Zoop campaign tagline for the 400-page Bryan Talbot: Father of the British Graphic Novel, co-written with J.D. Harlock.

There is only a little over a day left in the Zoop campaign for Bryan Talbot: Father of the British Graphic Novel, so get your copy right now!

Rebecca Oliver Kaplan: How did you meet your co-author J.D. Harlock?

Bryan Talbot: About two or three years ago, a young Lebanese academic, J.D. Harlock, contacted me and said, “Can I write your biography? I’m a big fan. I know all your work.” I said, “Yes,” and we started exchanging emails. After a week, it became apparent that he could only garner a certain amount of information from interviews with me, articles about my work, and reading my comics. He didn’t know about my private life, family, or the obstacles I’d overcome. So eventually, he came to me and said, “Hey, do you want to write it with me?” I’ve written much of it.

Writing the book has taken about two years. I work seven days a week here in my studio, and for two years, I stopped at eight every night, worked on the book, and then had dinner at nine. It’s nearly 400 pages, but we’ve got this designer, Alan Fisher, on board who’s done a great job putting together the book. It’s lavishly illustrated all the way through.

Kaplan: In a previous answer, you mentioned that you’d overcome obstacles in life. Tell me about an obstacle you overcame, but only if you are comfortable.

Talbot: I’ve been self-employed for 40 years. Jobbing illustrator is not easy. We’ve been up against the wall in debt because jobs haven’t been coming through. A few times, I’ve nearly quit but thought, “What can I do that isn’t drawing comics?,” so I’ve always stayed.

Then, when I was five, I had polio and was in the hospital for six months. I had to learn to walk again with crutches and everything. Thank God for National Health; because my parents were working-class birds, they couldn’t afford to pay for all that, but in Britain, it’s free.

The experience made me grateful for how the Labour Government came in after World War II and tried to make Britain a utopia. It succeeded for a while, e.g. free university education for anybody, with grants. When I went to college in the 1970s, I got a payment from the government. Fees were only introduced in Britain in the 1990s by the Thatcher Government. Former Conservative Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, and he was notorious, said that Thatcher was selling off the nation’s silver, and she sold everything. Before gas, electricity, railways, and water, those things were owned by everybody in Britain, they didn’t exist just to make money for shareholders.

Author’s note: Because “jobbing” is mainly used in the UK, the Cambridge Dictionary defines it as “someone who does not work regularly for one person or organization but does small pieces of work for different people,” like independent contractors and gig workers in the US.

Kaplan: What is the difference between British and American graphic novels?

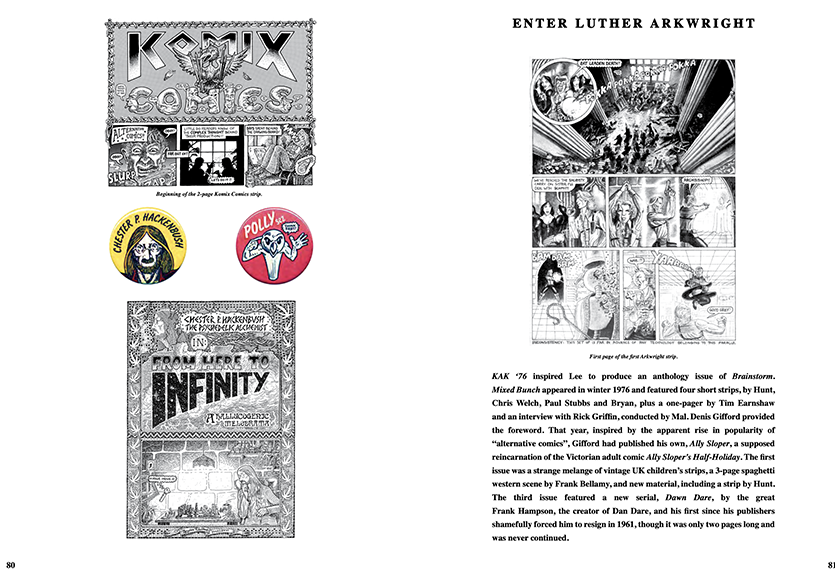

Talbot: Graphic novels are comics in book form. It’s a marketing term. Will Eisner‘s A Contract with God in 1978 is usually thought of as the first graphic novel because it was the first to use the term to sell itself. However, there were prototypes, Richard Corben‘s Bloodstar and Jim Steranko‘s Chandler. In Britain, there was Raymond Briggs‘ When the Wind Blows, published in 1982, and Posy Simmonds‘ True Love, serialized in October 1978, so The Adventures of Luther Arkwright has a slight edge on being Britain’s first graphic novel. October 1978 that’s the same month that Contract with God was published. I think that gives me the edge over the other two.

Talbot: In different sections (according to what books I was working on), it follows the creative process from ideas to structure to script and even to drawing materials. It also shows how someone (i.e., me) with no contacts in the comics industry and no grasp of publishing eventually made myself into a professional comics artist by sheer persistence.

Kaplan: How will your biography contribute to the history of the comic book industry other than your contributions to the medium as a whole?

Talbot: I give a general history of comics as part of the background, from the 1950s onwards, sometimes very general, sometimes on specific titles, publishers, or trends as they relate to my story. I also chart the origins and development of the graphic novel, starting with underground comics. I also chart the growing acceptance of the medium as a legitimate art form.

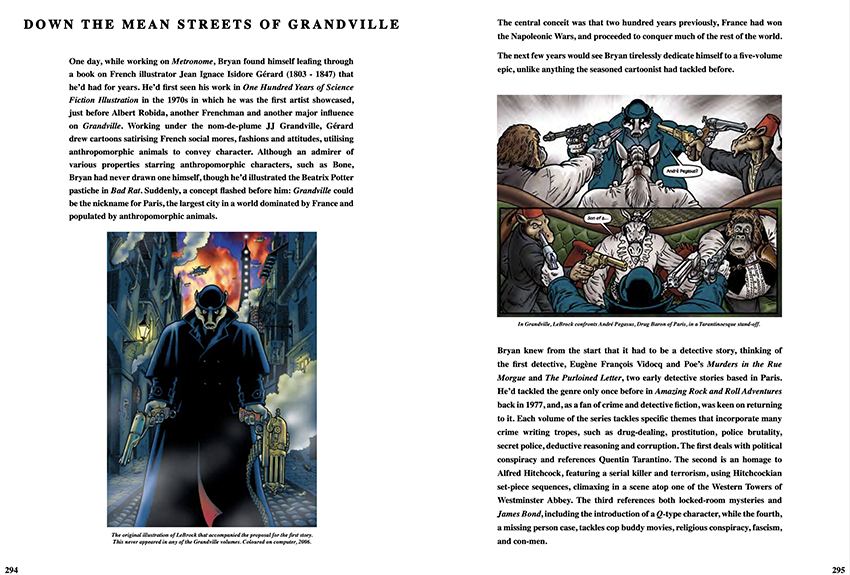

Kaplan: With The Comics Journal, you discussed your decision to make LeBrock a badger in Grandville. Can you tell me more about your inspiration for the character?

Talbot: I was following in a tradition of stories using animals as characters, right back to Aesop’s Fables, and for centuries in legends and folklore, and even in cave paintings and cave sculptures, you’ll see animal figures. Of course, anthropomorphic animals are also in all world religions and mythologies. In the Bible, there’s the anthropomorphic snake in the Garden of Eden. There have been animals in stories as long as people have been telling stories. And as a kid in the 1950s, I grew up reading comics full of anthropomorphic characters, like Freddie the Frog and Rupert the Bear, so I was also harking back to that.

For Grandville, I wanted a two-fisted character with the deductive abilities of Sherlock Holmes who was happy to beat the living spirit out of a baddy to get information. Badgers are very tenacious and can be quite vicious. I liked this combination of intelligence and brute force because, in the story, he’s a working-class badger in a society where the higher classes run everything. He’s become the first working-class detective in Scotland Yard, so he’s got that going for him too.

It’s fun writing complicated detective stories and putting clues there for the reader to pick up on if they’re following closely enough while still not giving everything away. In a good detective story, the reader should think by the end of it that they could have solved it given time. Aristotle said, “The ending of stories should be both unexpected and inevitable,” and detective stories more so.

Kaplan: How did you land the job doing the Hellblazer Annual?

Talbot: The writer, Jamie Delano, apparently asked to work with me on the first Hellblazer Annual, which is partially set in the 5th century, because he knew I was good at historical stuff and must have thought I was suitable for that. The best part was reworking the Arthur story to make it as gritty as it would have been with ancient British things. Usually, you see something on King Arthur or Camelot, and everyone is in medieval armor from about 1000 years later and in medieval castles. At the time, it was wooden castles on little hills with a wooden wall around them. After that, I was asked to do quite a few DC things.

I talk about this in the book: When I was about 11 or 12, I thought, “Oh, I’m too old for comics; that’s kid’s stuff,” and I gave all the comics away, which were DC Comics. I discovered Batman when I was about eight years old through the old Columbia Pictures Batman movies they used to show at the cinema. Although when I saw them, they were already 20-30 years old at the time, that’s how I discovered the Batman comics. I read a story by Archie Goodwin called “Collector’s Edition,” and drawn by Steve Ditko in this fantastic detailed crosshatched style, and it blew me away. I discuss this considerably in the book because I thought, “Wow, this is what comics are capable of; they’re not a kid’s medium after all.”

So when I finally met Archie, it was great. We had dinner with a couple of other people when he was at a comic convention in Glasgow, and I said to him, “What are you doing now, Archie?” He said, “Well, I’ve just become the editor for Legends of the Dark Knight,” which was a title that I read at the time. So I said, “Oh, I’ve got an idea for a Batman story,” and it was an idea for a story I had as a teenager. He said, “What is it?” I told him, “Well, Batman doesn’t exist. Bruce Wayne exists. Yes, his parents were killed by muggers, but he doesn’t inherit a fortune, he inherits huge debts and grows up in an orphanage until he runs away. By the time of the story, Bruce Wayne has no power in this world, so he escapes into vivid delusions of being a costumed vigilante by night and a billionaire playboy by day,” and he says, “Oh, I’ve not heard anything like that before. Send me a proposal.” Except, I didn’t do anything. I thought, “Well, he must say this to everybody.”

Six months later, I was at the UK Comic Art Festival at the DC party, and when I walked in through the door, Archie said, “You never sent that proposal.” I said, “I thought you were joking.” He said, “No, now send it.” I did, and he accepted.

Kaplan: What appeals to you about the crosshatching style?

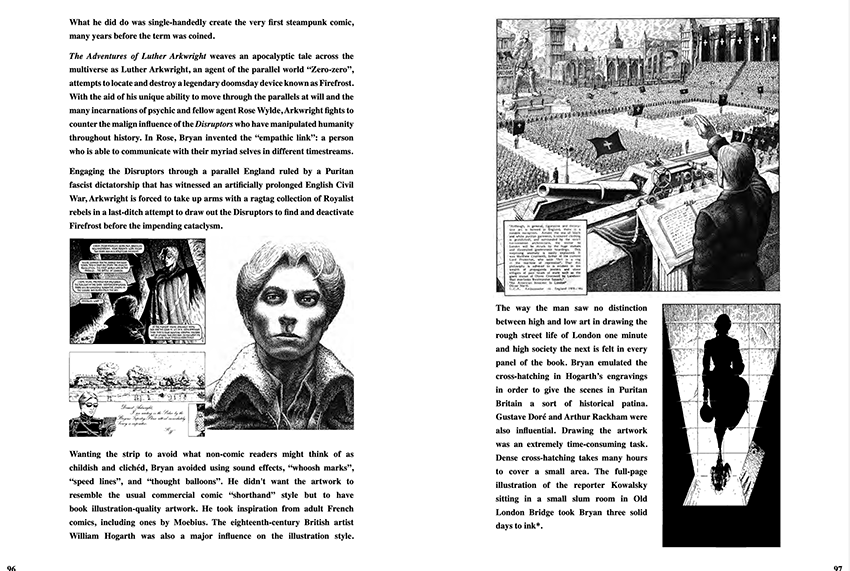

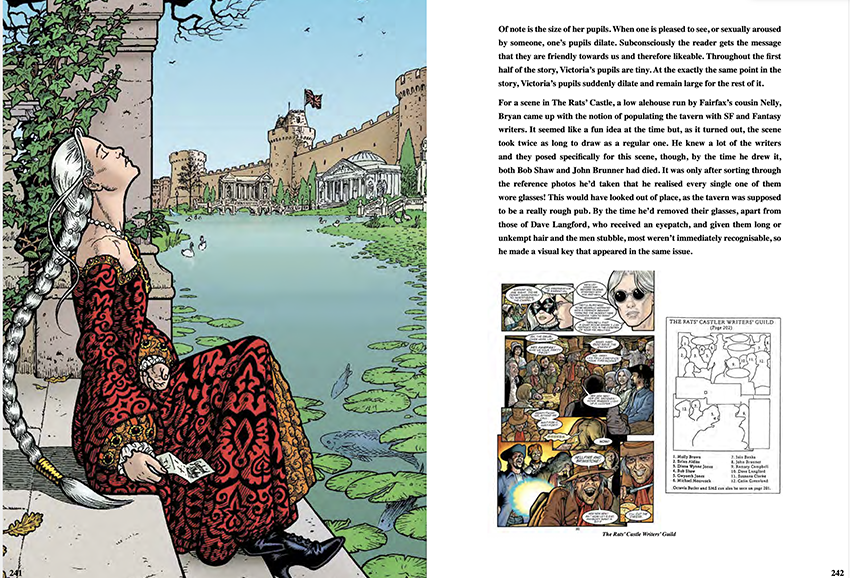

Talbot: Well, in Alice in Sunderland, it was about stories and storytelling, so the artwork changed style according to the type of story being told. Some suited black and white and sort of suited color. But with the new Arkwright, I’ve tried to return to the original black-and-white feel and used this incredibly time-consuming crosshatching style that takes forever. I’ve got pains in my wrists now because of the repetitive inking.

I used it in the first Arkwright book because although it’s science fiction, it’s not spaceships and things, it’s like a parallel world. I wanted to give this historical feel to the story. So I looked at old artists like Gustave Doré and William Hogarth, whose etching techniques I particularly admire. I was trying to do a version of that, I suppose. I was also influenced by the inking techniques at the time of Mobius and Robert Crumb, who used a similar sort of crosshatching. With these multiple layers of inks, you must build up textures slowly with layer after layer of fine lines until you reach a density. Like one of the pages in the original Arkwright took me three solid days to ink.

The crosshatching was also a reaction. For Arkwright, I wanted to do something with quality illustrations. At the time, especially in the 1970s, practically all mainstream comics were done in this so-called “shorthand style.” I wanted to get away from that, giving it this historical feel but also making the pictures very, very rich.

Kaplan: I am interested in creative partnerships and how couples navigate collaborations. You’ve collaborated with your wife, Mary Talbot, on multiple graphic novels. What is that collaborative process like?

Talbot: Mary researches and writes books, and I usually do the artwork. With Mary, it’s an extremely close collaboration. As I’m drawing it, I’ll suggest changes in dialogue to Mary, splitting a panel into two panels, or the other way around, that we can put these two panels into one. But having said that, when we’re in the same house, sometimes, the suggestions are on an hourly basis. And she’ll make some suggestions on the drawings that I’m drawing.

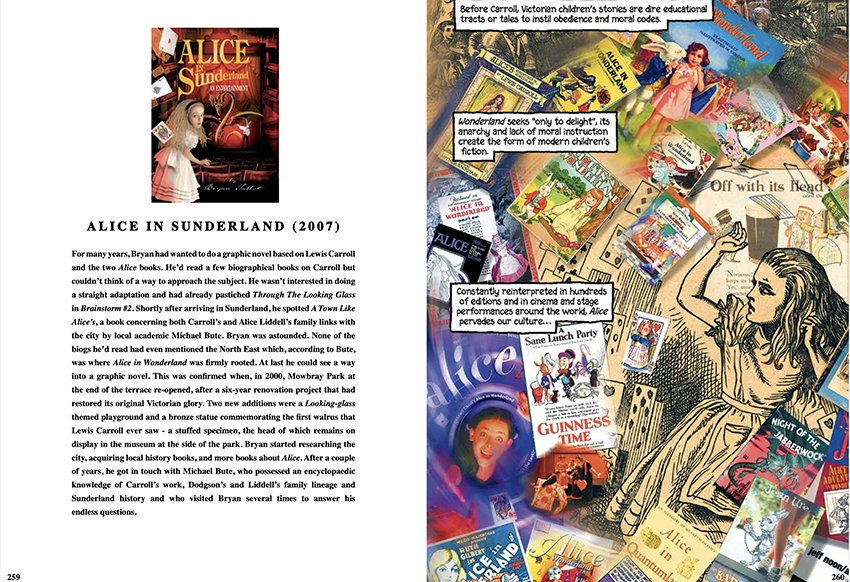

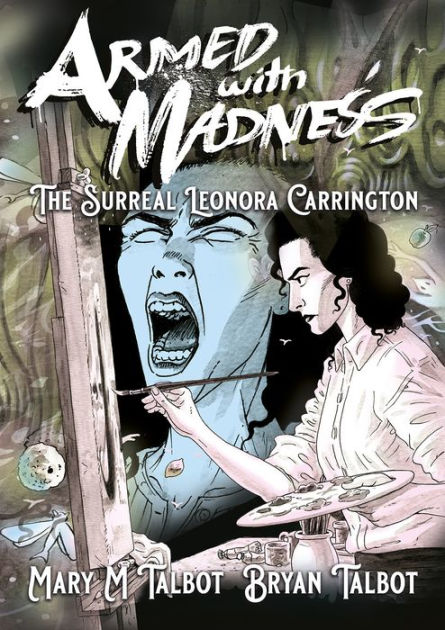

The first book she did, Dotter of her Father’s Eyes, was after she’d been an academic all her life and took care of her retirement, so when she gave me the script, it was more like a stage play with scene description, dialogue, and casual actions noted. Then, by the second one, Sally Heathcote: Suffragette, she had learned, and it was a full proper comic strip. I’m currently about three-quarters through drawing the fifth one, Armed with Madness: The Surreal Leonora Carrington, a biography of the English surrealist artist Leonora Carrington, coming out in Spring 2023 from Self-Made Hero.

For a lot of collaborations in commercial comics, basically, someone writes a story and then sends the editorial commission script to the artist, and that’s it, the end of the collaboration. When I was working on those scripts with Neil and Pat Mills, we were on the phone often, sometimes daily, talking about the pages. I always used to fax. On Sandman, Neil and I always worked up to the wire. Very often, I’d be drawing the page and then faxing it over, and then he’d continue writing on it, and sometimes he actually drew things that he’d see and then write into the script later on. It’s different than working with Mary.

Talbot: It was a big dream of mine after going to Angoulême and Lucca in Italy, where they take over the town, to have something like that in Britain. There have been comic conventions in Britain since the 1960s, but they always take place in a little convention center or hotel. Whereas, the proper European style convention, the town takes part.

Over ten years ago, I was approached by a professional festival organizer, Julie Tait, about doing a proper comic festival in Britain. I responded with a long email describing in detail what a comic festival should be like, basically it’s Angoulême. I told her that she should go someday if she wanted to see what a festival is like, but it’s hard to get a hotel room, and she emailed me straight back, saying, “I booked a room. I’m going in a month’s time.” That happened in November, and the first LICAF happened the following October.

LICAF is similar to a European festival with banners in the streets, comic displays in shop windows, and events taking place all over town. We have two or three exhibitions around town, well, we have in the past, anyway. The comic marketplace is free to the public, so you get members of the town, and non-comic fans, going in. Every year, we get loads of people buying comics for the first time, which is great, and the whole town celebrates comics: it’s on the local radio, the local colleges are involved, and the local schools have programming running on them. It’s as inclusive as we can get. For the first time this year, we’re moving to Windermere, about 12 miles away.

I’m saying, “we.” I don’t do any of the organizing. I just helped start it off. But I’m looking forward to this year because, for the first time, we actually have a table. Like, we have a booth selling stuff.

Bryan Talbot: Father of the British Graphic Novel was funded in under a day, get your copy right now!