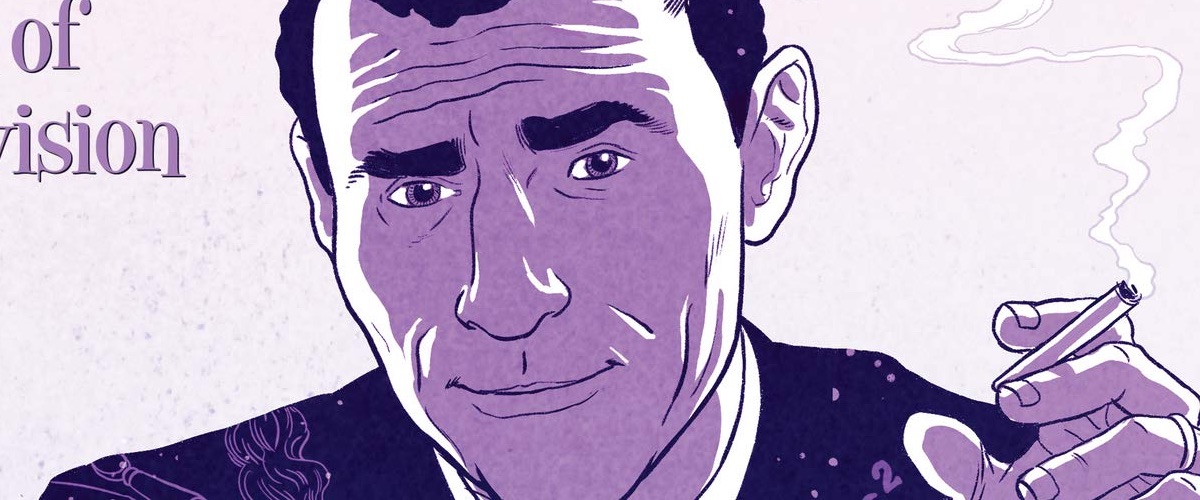

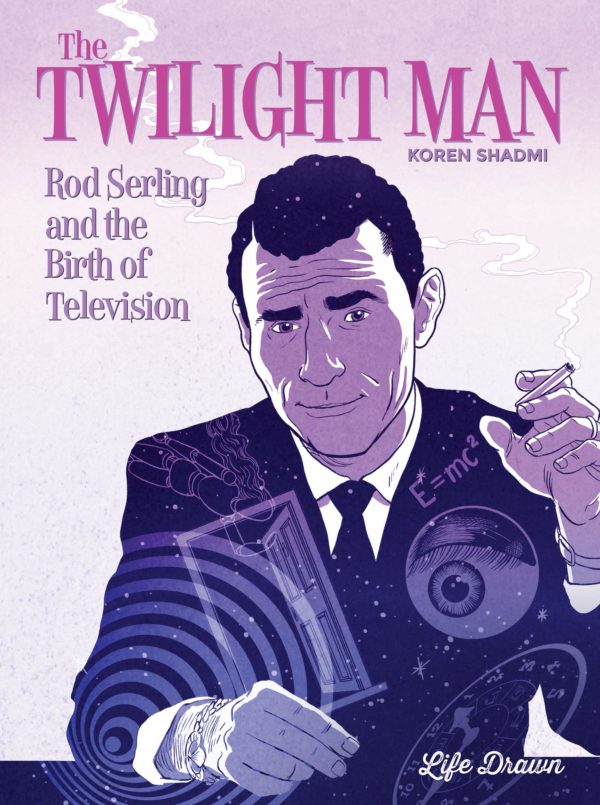

The Twilight Man: Rod Serling and the Birth of Television

By Koren Shadmi

Humanoids Life Drawn

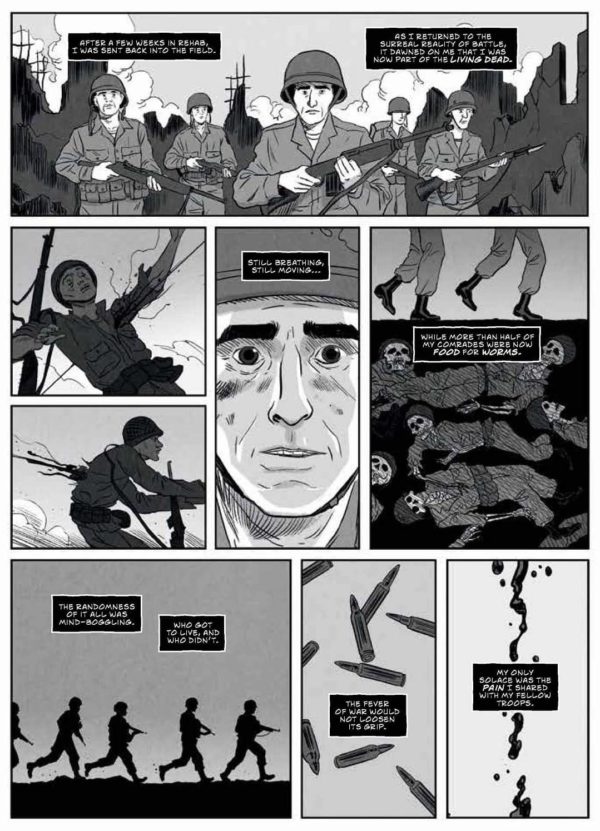

There is a myth that America has always been desperate to believe about its involvement in World War II, one that clings dangerously to outdated and destructive concepts of masculinity. I think many people of my generation have encountered the shatter moments when one of our family elders hints at the idea that what they thought about a relative serving in World War II might not be the reality. The conversation could be about a grandfather or an uncle. Usually one or the other. “He was never the same when he came back,” the sentence usually goes.

But if something was wrong, it was ungrateful for the returning soldier to express that. His family, his community wanted something to be proud of, and that responsibility to create silence and suffering. The GI bill and suburban growth heralded in the prosperous post-war era, making the rewards for fighting huge enough that a veteran could convince himself that really nothing was wrong. How could anything be wrong?

But that darkness lurked in the country, creating a generation of men for whom everything seemed … off. Everyday life had a foreboding aspect to it. Every moment might bring the unexpected.

Enter Rod Serling and The Twilight Zone, which best expressed that hidden unease.

Koren Shadmi’s biography of Serling, The Twilight Man, opens with Serling’s entrance into the military follows him through training and into the Pacific theater where he encounters various horrors that marked him for life. It’s an unexpected focus for a book that is subtitled “Rod Serling and the Birth of Television,” but it’s crucial. These are the years that Serling learned the dark depths of the human soul and was able to peer straight into it, even in regard to his own mortality.

War seems to have prepared him for the grind of being a writer and fighting for his way in the world. Working his way through radio, he eventually enters the world of television where he is enticed by the apparent freedom allowed writers with elevated goals for their work. But Serling’s war-time experience groomed him to be a writer who addressed dark topics that were often critical of the accepted society, and as he fought to write about the topics he found concerning, especially racism, he butted up against the rigid barrier that the networks had set up to prevent anyone from peering into the dark truth that had settled onto the ground everyone plodded across, the same one that kept society from addressing the demons that lived in the souls of ex-military combatants.

The Twilight Zone was Serling’s solution to tackling difficult topics in an adult fashion. If you could disguise it in genre terms, you could slip past the gatekeepers trying to spare Americans from having to ever look into the mirror. But Serling was constantly looking in a mirror, even as he tried to allow his crazy success to act as a salve. The pressure of his work combined with the escalating paranoia and undercurrent of ugliness in America worked together to undermine the high of big bucks and applause. The terror and depression that were born in the war continued to act as a mist around him while these other forces coalesced alongside them.

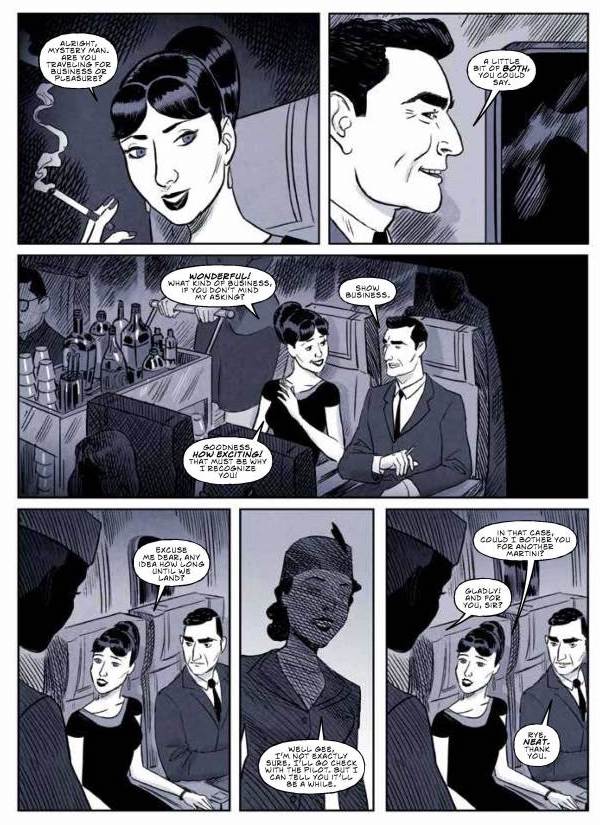

In The Twilight Man Shadmi renders Serling’s life in an aesthetic similar to that of his most famous work. The clean black and white presentation is obviously meant to evoke The Twilight Zone, and the framing device of Serling narrating his own life adds to that conceit. But Shadmi never lets the dark aspects lurking within Serling’s psyche — and therefore his story — to overtake the book. Instead, this is a story of trying to move beyond these predators’ grasp and working for a happy life.

The irony is that Serling’s success never gives him power, and the establishment he criticized within his work ultimately overtook him. Even as he found a way to utilize his personal demons, it’s those on the outside that got the best of him.

But there’s another irony to this — television as we know it now, with pay networks and streaming channels becoming the center of broadcasting, owes a debt to Serling’s early pioneering of the form that set a high standard at the beginning, and which demanded that television was a format that could intelligently comment on current events, and even function as artistic protest. It might have lost its way for a few decades, but ultimately a generation of new TV show creators saw the potential in what could be achieved by the form — including in the typically maligned genre shows — and we only have to look back to Serling to trace that direct line. In the end, from whatever Twilight Zone his spirit now lurks in, Serling won his war.