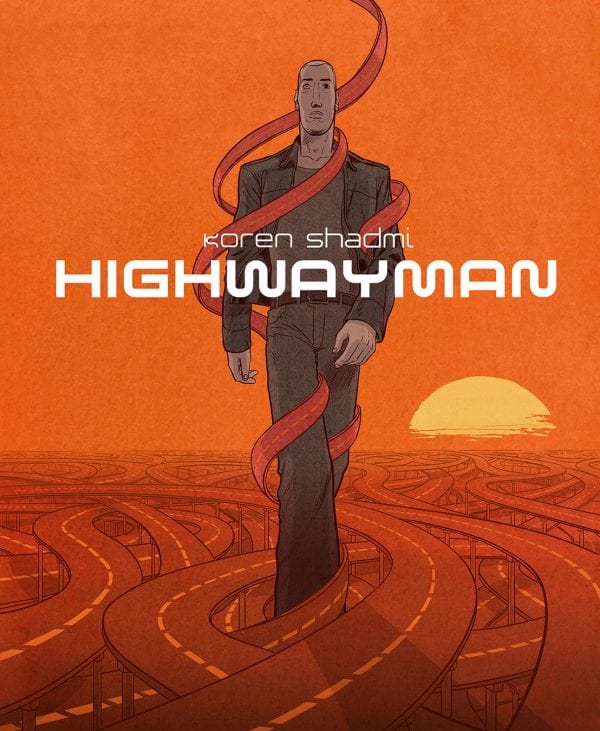

Highwayman

By Koren Shadmi

Top Shelf Productions

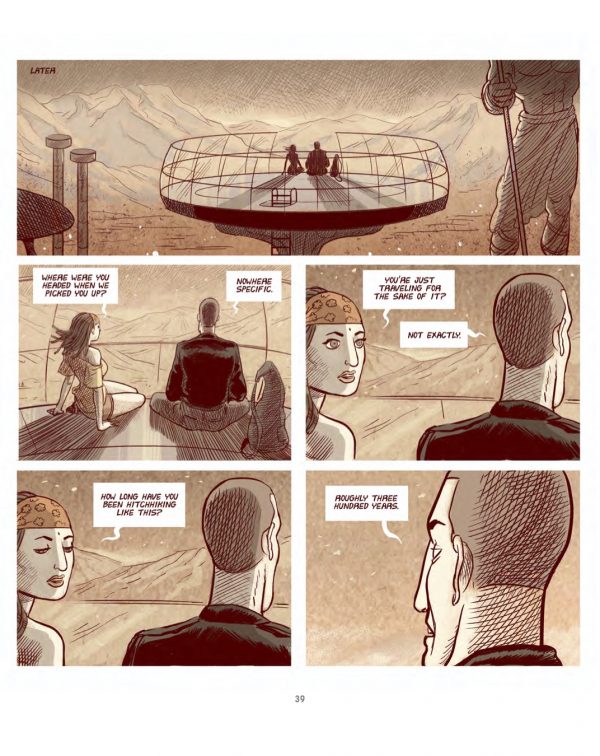

Who is Highwayman? That’s one of the central questions of Koren Shadmi’s contemplative science fiction story, but there are many and each functions as a prompt for many others. As he calmly walks the landscape throughout the ages, the simple answer is that he is Lucas, but the reasons Lucas walks the landscape and the reasons he’s so obtuse about his purpose feel like better descriptors who he is than the name he is given.

A quick internet search tells me that the basic meaning of the name Lucas is “light” or “bright” or “shining” or “luminous,” and while Lucas’ presence offers a specific allure that one would equate with a person exhibiting any of those as qualities, his words offer less in the way of those qualities as metaphors for finding out the truth.

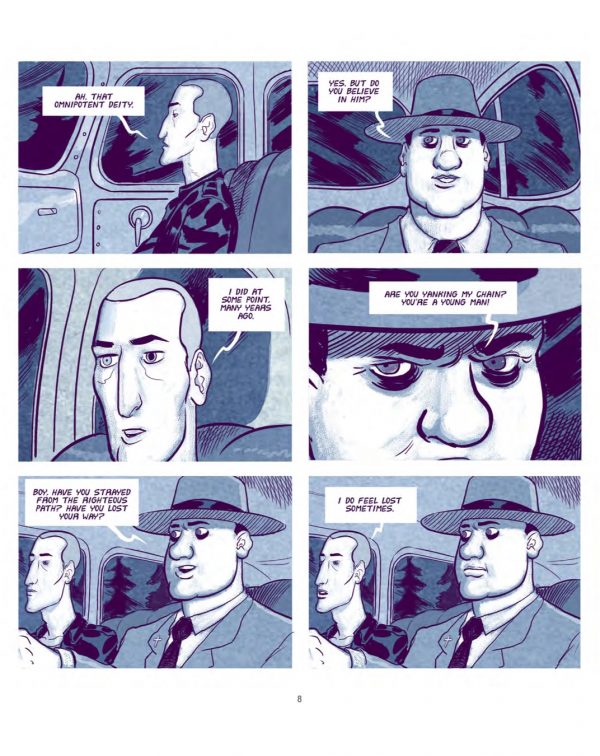

In Highwayman‘s opening sequence, Lucas is picked up hitchhiking by a Bible salesman sometime during World War II and the man’s pitch is directly focused on the message of those Bibles he carries around, but mostly, we find, as a way to make a quick five bucks. The confusion is clear and the wider point of depicting it is also — religious belief began as a way to explain the universe, but by the 20th Century, had turned into yet another commodity to provide a comforting truth. The salesman still clings to the lessons of the scripture even while he uses that as a sales pitch to entice buyers.

Lucas, on the other hand, has no such clarity. He is obviously immortal. He has obviously seen much and reveals little. And he obviously has no idea why. Why is it that the Christian god offers relative clarity when, in fact, Lucas has found himself in a situation that has given him a transcendent place in the world of mortals, as if a gift from a greater being, but without anything resembling a clear mission, a message that’s meant to be passed on, a code for people to embrace, or an explanation of how the universe works.

As time passes, Lucas continues wandering apparently aimlessly, left to conceive of his own purpose, to happen upon the meaning of his existence in his own time, which is, apparently, forever. Without a predisposition to communicating ultimate truth, without the motivation to create religion from experience, Lucas just lets life on Earth happen to him and wanders through multiple instances of the human foibles as they condemn humanity to further self-destruction. Occasionally Lucas intercedes in a mild way, but often giving the impression that he understands himself as ultimately helpless — and even when he encounters others who read the situation differently, it still feels as if they have been left on the stream without a paddle, too. They’re just more decisive about other ways to overtake the flow and take command of their path, even if they’re not exactly right.

Highwayman evokes a 1970s science fiction vibe in which philosophy and mysticism wind through a post-apocalyptic landscape. That landscape becomes a stage for the acting out of civilization’s weaknesses, and is, in a way, as much El Topo as A Boy And His Dog. Lucas is Shadmi’s spaghetti western figure, a loner wandering through the ravages of the land, just as usual in the form of a desolate desert that hints at apocalypse, similar to the one Logan 5 and Jessica 6 took flight across as the only apparent alternative to the youthful domed dystopia they’ve escaped.

And as in Logan’s Run, the solution to it all is simple. In Highwayman, it’s somewhat related to the concept of a tree falling the forest and the question of whether without an observer, reality is real. And isn’t the religious concept of a god much the same as the concept of an observer, just warped over time?

Regardless, on the scale of billions of years, simple is typically complex, and Shadmi takes that understanding to its logical and beautiful conclusion in Highwayman. That humankind, or at least some of humankind, considers itself the center of the universe, the standard by which all other existence is measured, is not only proof of short-sightedness, but of a lack of appreciation of beauty and excitement. It’s the possibility of infinite diversity, and because of that continual evolution, that makes the earth in particular and the universe in general so thrilling to chart in context of life.

Shadmi skillfully mixes together this sweeping kind of mystical scientism with an on-the-ground epic of personal journey in order to craft what adds up to the best sort of science fiction in a culture where too often the genre is handed over to action and literalism.