The Scarfolk Annual

By Richard Littler

William Collins/HarperCollins

The Scarfolk Annual is not necessarily a comic book, but its existence pulls from a form of book that has traditionally included comics. Indeed, The Scarfolk Annual boasts two comic stories inside — “Waugh in War,” starring our hero Ben “War” Waugh as he tries to instill a classist backbone into modern soldiers, and “Kak From the Council,” an ethereal owl representative of the official Scarfolk body of governance who intervenes in a suicide attempt — as well as a one-pager that should properly deflate everyone’s self worth. All the comics drive home the essential message of any Scarfolk effort — those in charge care enough to control your life and you should trust it.

The idea of a British annual never crossed the ocean into the United States, but it always struck me as a bizarre, lovely thing. Each year in the U.K., typically during the Christmas season, affordable hardcover books that tie-in with popular properties, often TV shows, sometimes comics magazines, are published. They contain short stories, articles, educational pieces, games, puzzles, artwork, and, of course, comics. They’ve existed for things like Doctor Who and Thunderbirds and Man From Atlantis and Beano and Viz and The Osmonds and plenty more.

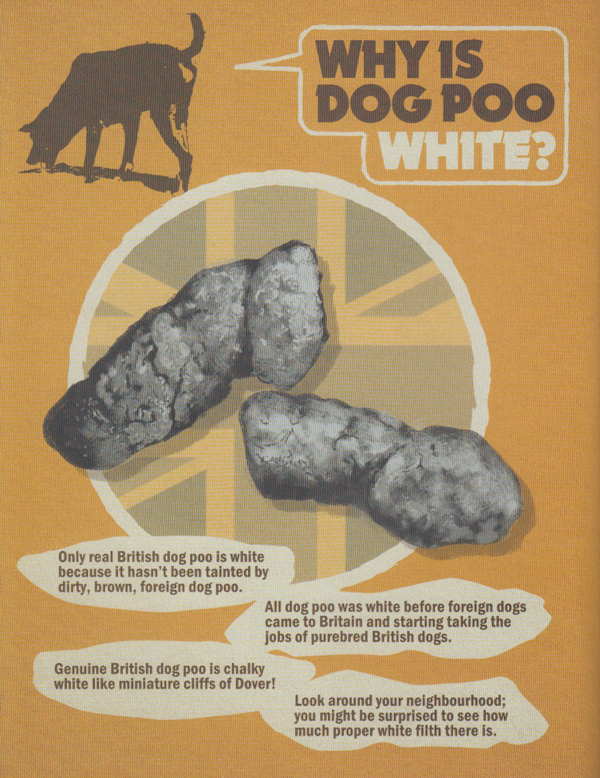

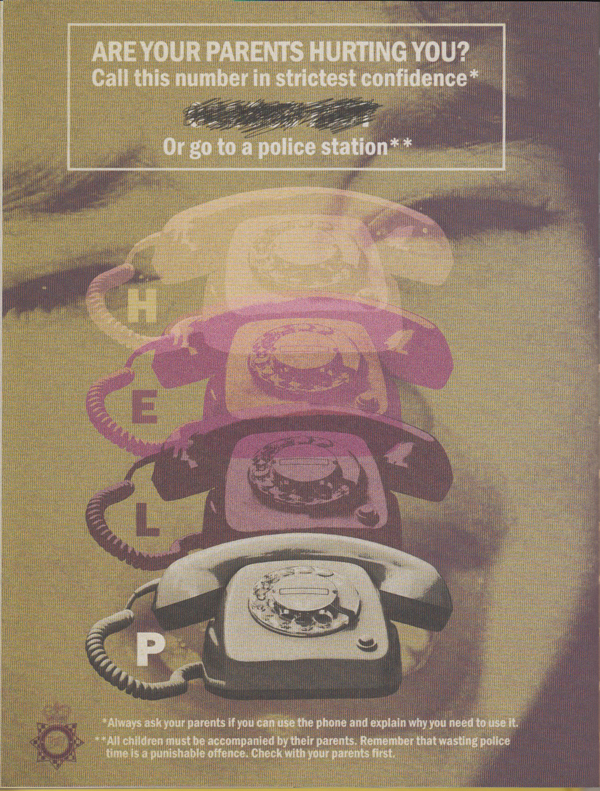

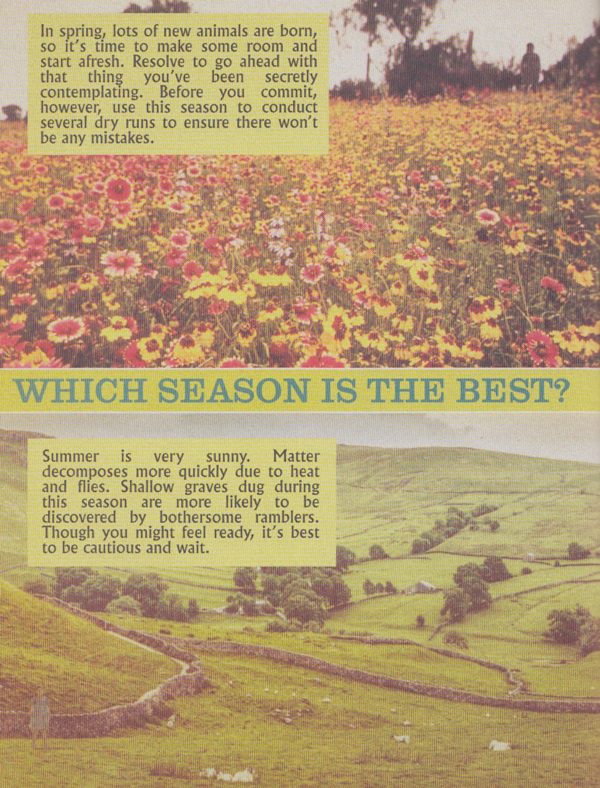

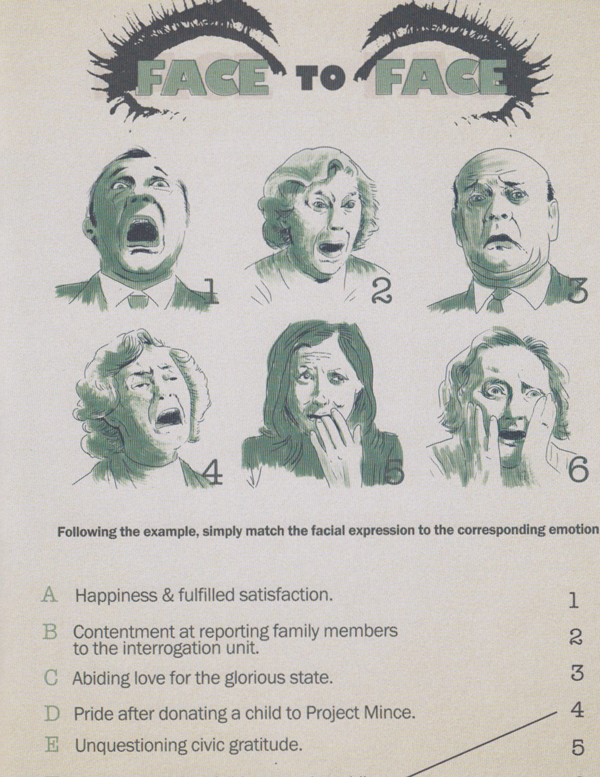

The Scarfolk Annual is a parody of that form and exists from the conceit that it was a publication of the Scarfolk Council that was distributed amongst the populace of the town and used to perpetuate its totalitarian agenda with its citizens, therefore filled with comics, stories, puzzles, and more that encouraged things like adhering to interrogations and happily confessing of fictional crimes and ignoring safety warnings and embracing false information and hating foreigners.

Scarfolk itself, in cased you missed it, is an online project by Richard Littler that in its original — and I would say purest — form was a series of brilliantly designed informational posters from the government of the fictional Scarfolk to the citizens of the fictional Scarfolk giving frantic directives about disease, nuclear war, crime prevention, accident prevention, and more. They are hilarious and brilliant works of art that sometimes take a moment or two to realize that you are viewing satire rather than something actually put out by the British government — which makes it not surprising that the British government recently included a Scarfolk rabies poster in its official history of government communications by accident.

The thing about Scarfolk is that while it is satire that pulls from a very particular blend of references — 1970s children’s television, public safety films, dystopian fiction, 1970s graphic design, official government publications, aspects of the folk horror genre, and plenty more — it proved to be far more relevant to the current Brexited nightmare that is the U.K. than most of us probably would have expected. What’s most surprising to me, though, is how prescient it is to an American audience that does not share the same set of cultural references or even governmental structure.

I think the reasons for this resonance across cultures align Scarfolk most closely with Douglas Adams. Littler’s narrative voice is as singular and sublimely witty as Adams’ was, and his observations through Scarfolk are as on target and inventively addressed as anything in the Hitchhiker’s Guide series. But in adding the visual element to his satire — a crucial element, I should add — he translates the sensibility to a 21st Century audience in a way that no other writer descended from Adams has come close to achieving. And Littler’s attention to detail within the visual element is remarkable, revealing an impressive ability to make jokes visually that are equal to the words.

And so in The Scarfolk Annual, there is no one piece that stands out as pivotal on its own. Rather, it is the culmination of the parts into the whole concept that makes it so successful and important. That’s not to say, for instance, that the essay “What is a Library?” which begins by defining libraries as “a place where state-sanctioned books, periodicals, maps, and prints are stored and made available to the public,” and ends with an addendum explaining the tightly-defined term “public” in context of the library isn’t damn amusing on its own. Or that the Foreigner Identification Badges aren’t darkly funny. Or that the “How to Survive a Nuclear Thing” instructional section isn’t great for grim giggles. But peppered with everything else in the book — the nonsensical and mildly dismissive “Space Facts,” the step-by-step guide to finding out if you will become a ghost after you die, the conspiratorial history of the Albion Estates — the entire package comes together as a document of authoritarian hilarity. It’s the feelgood totalitarian guidebook of the year!

However, the darkest lesson of Scarfolk is that the joke is on us, even in America, because Scarfolk is not an entirely fictional construct. Consider that on one side of the political spectrum we have a group of people who say they distrust government and want it out of their lives, but continuously vote for members of a political party that have slowly been constructing a surveillance state that elevates the role of law enforcement and military action in keeping peace and stamping out dissent, and routinely puts laws into place that ensure a specific segment of the population always holds power in the financial form, which translates into the political form.

The opposition, meanwhile, holds to the belief that the state should protect us and care for us. It should provide us with our basic needs and should oversee that no one citizen is allowed to seize power through our financial resources. It also believes that aspects of the system can defeat authoritarianism through procedural structures and the sanctity of the vote of its citizens, despite the fact that information is dispensed through a series of corporate channels that have their own financial interests at the heart of the dispensation and therefore cannot guarantee that the information is entirely correct, is not in service of someone, and, in fact, does not obstruct the basic view of the opposition that the state should protect us and care for us.

Meanwhile, there are people on both side of this political divide who advocate some form of punishment — typically public shaming and whatever repercussions result from that — for those who express repugnant beliefs that they haven’t actually acted on or points of view that are outdated or ideas that do not conform to a code of beliefs by certain historical bodies, often religious. Thought crimes abound in modern America.

We already live in Scarfolk, just without the stellar graphic design to keep us amused through this dystopian nightmare.

And if you’re having difficulty digesting my rant at the end of this review, in the words of the Scarfolk Council itself, for more information, please reread.