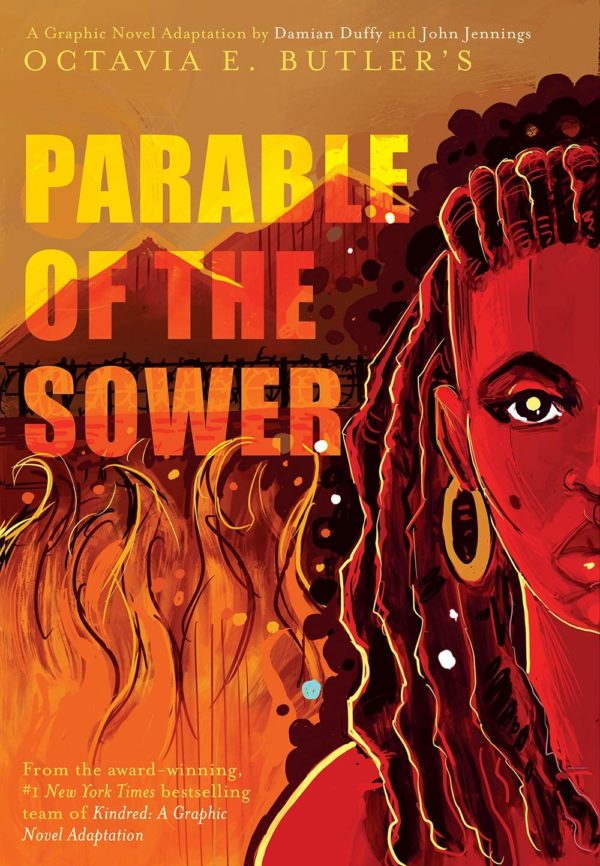

Parable of the Sower

Written by Damian Duffy

Illustrated by John Jennings

Abrams Books

Adapted from Octavia Butler’s 1993 novel of the same name, Parable of the Sower is one of those works of science fiction that is so prescient, so embedded in the times that it’s amazing to realize that it wasn’t meticulously designed to comment on the year 2020. All the elements were there in 1993 for an insightful person like Butler to bring them together in this particular mix, but sometimes it’s astonishing to realize that people of such vision exist at points in history where they are laying down in artistic terms what feel like the inevitable outcomes of these elements.

In the hands of writer Damian Duffy and artist John Jennings, who previously successfully adapted Butler’s novel Kindred and won an Eisner for it, material that already has such philosophical and political fortitude is pretty much set on fire and allowed to run screaming through our streets to announce not only that the future we live in was never uncertain, but even if we descend into a worst-case scenario, as Butler painted in Parable of the Sower, there is still hope on a singular human scale, and getting through the worst requires those shards of hope to join together and do the work as a community.

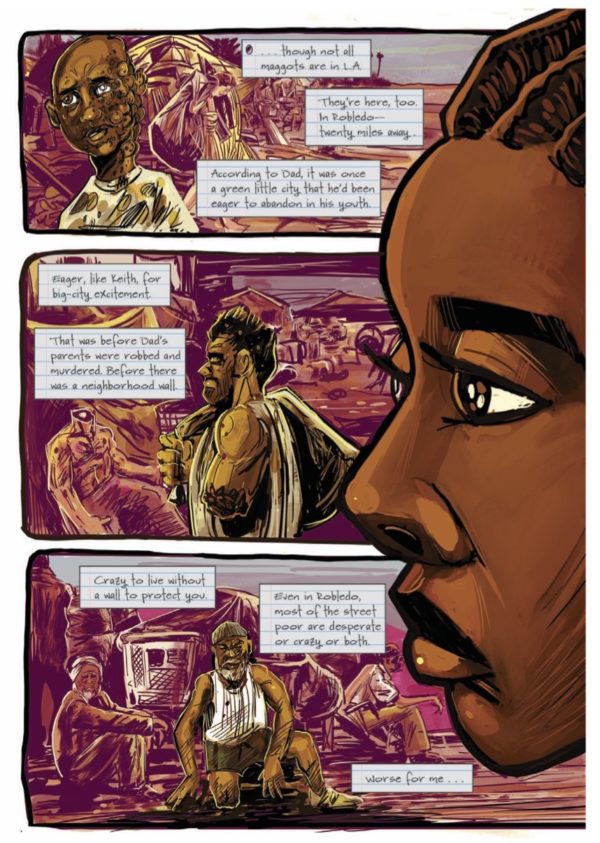

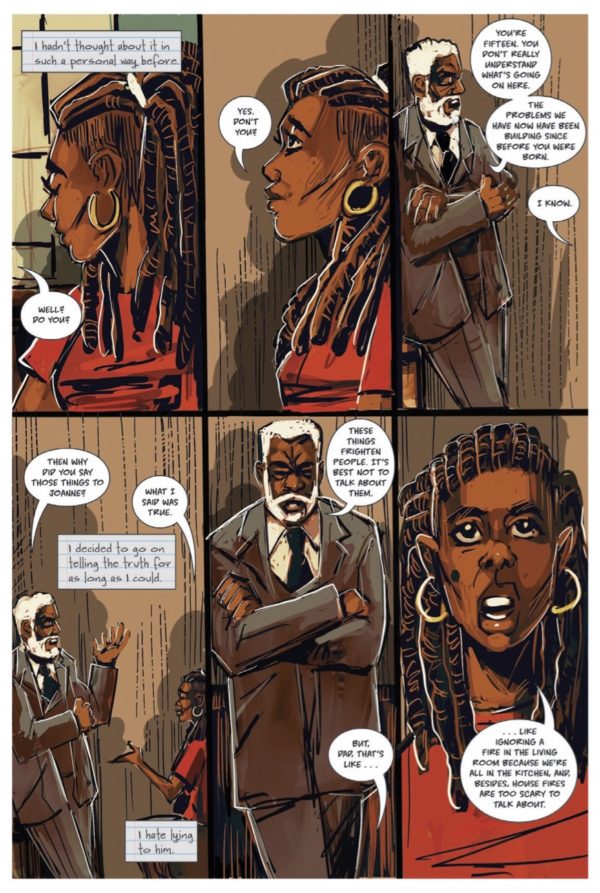

Focusing on teenager Lauren, who lives in a ragtag, struggling gated community on the outskirts of Los Angeles with her minister father and his second wife and their children, Parable of the Sower documents the human inclination to hunker down in the face of disaster, to scrape by while clinging to the hope of being saved, and the inevitable outlook of a younger generation that never experienced a world before it crumbled, and so approach the new one as the only world they’ve known.

Lauren not like the other people in her community for a number of reasons, but there are two that cause her particular emotional separation. One is that she was born with a condition called hyperempathy, which causes her to share extreme emotions in others and brought on by her mother’s use of a drug called Paraceto. The nature of hyperempathy is left open and could be interpreted as an actual extra-sensory ability or a psychological condition or a metaphor. It’s also left up to the reader to decide whether it is a disability, a superpower, or a form of difference.

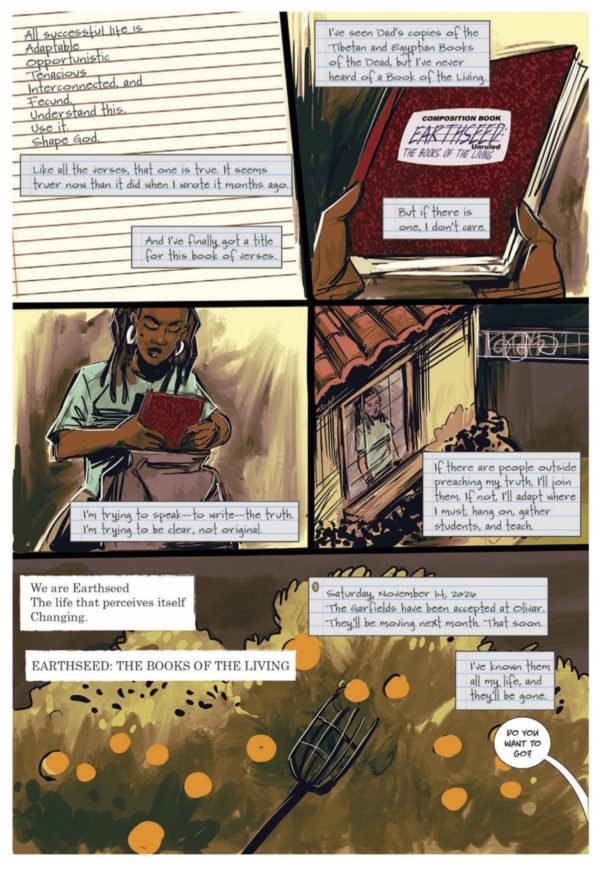

The other is the journal she keeps to herself that is less a diary and more a religious manifesto in the form of poetic spiritual searching. Building a new religious outlook that she calls Earthseed, Lauren’s writing examines a concept of God as change, folding aspects of various other religions into her own ideas, with the singleminded of goal of eventually building a religious community around these ideas and looking to the stars in order for this community to enact them further within the universe.

But the world is falling apart outside the compound. Chaos reigns on the streets, with looters and marauders everywhere, often fueled by drug abuse. Resources are thin and though a governmental system still exists, its one that controls the resources through capitalism that sets exorbitant prices for needed items that are sold through stores with armed-guards. Environmental disaster is behind the struggle of civilization, with climate change at the center of it, and basic nourishment can only be solved through creative means using unexpected materials, as well as good fortune in agricultural pursuits.

There’s only so long that the community can hang on, though, and in Parable of the Sower, we watch Lauren’s journey from young philosopher to true spiritual leader in a tense narrative that doesn’t always make you feel so certain that what she is building is going to make it through the constant terror unleashed in the world.

Duffy and Jennings do a wonderful job of retaining the qualities of Butler’s original work that makes it so important. Crucial portrayals of race and gender concepts in context of the apocalyptic narrative remain and elevate the work far beyond most end of the world stories, and Duffy does well transplanting the religious and philosophical ideas that stem from Lauren within a graphic novel format that helps those headier aspects frame the action that Jennings spells out visually.

Furthermore Jennings’ work in the book is beyond stunning, with a woodcut quality that gives it an effective folkloric feel that is appropriate for the story of a religious movement during the end times. But this stylistic approach doesn’t undercut the presentation of the characters as individual people with inner lives, and Jennings is able to extend the emotional quality of their experience through the world around them. With the threat of fiery oranges around them and the ragged clutter of shadowy human detritus lurking around the panels, it’s as if the reader develops their own version of hyperempathy through the story-telling.

Butler would release a sequel in 1998, Parable of the Talents, and though I’ve not seen any mention of Duffy and Jennings tackling an adaptation of that book, the supreme artistic success of Parable of the Sower can at least make me wish for it to happen.