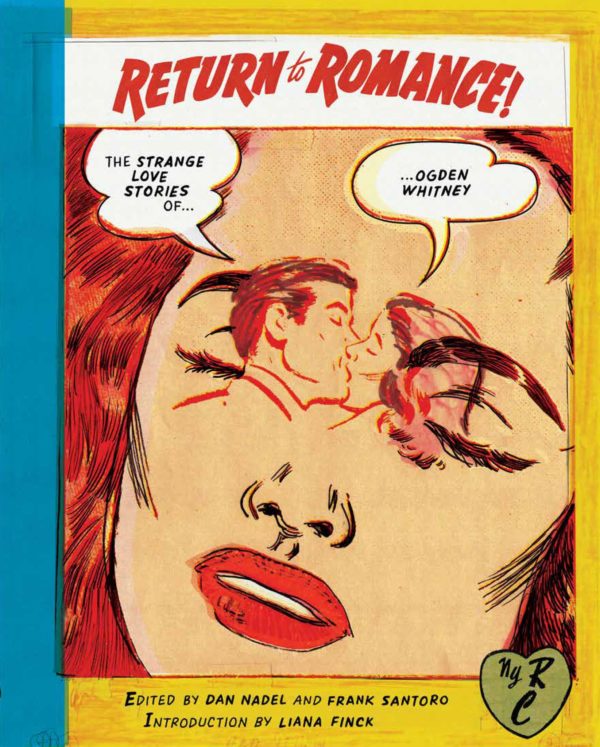

Return to Romance

By Ogden Whitney

New York Review Comics

Ogden Whitney might have remained relegated to comics obscurity if not for catching the eyes of Dan Nadel and Frank Santoro, who bonded over their mutual love of his work when they first became acquainted in 2003. It’s been their goal to put together a collection of Whitney’s romance comics ever since and Return To Romance marks the completion of the 15-year journey.

Most comics fans know of Whitney as an artist on Sandman in Detective Comics in its early days, but he also created Skyman and in the late 50s Herbie Popnecker. But the Stoneham, Massachusetts native — he was raised in Minneapolis — is being paid tribute here for his romance comics, which ran in My Romantic Adventure in the 50s and 60s.

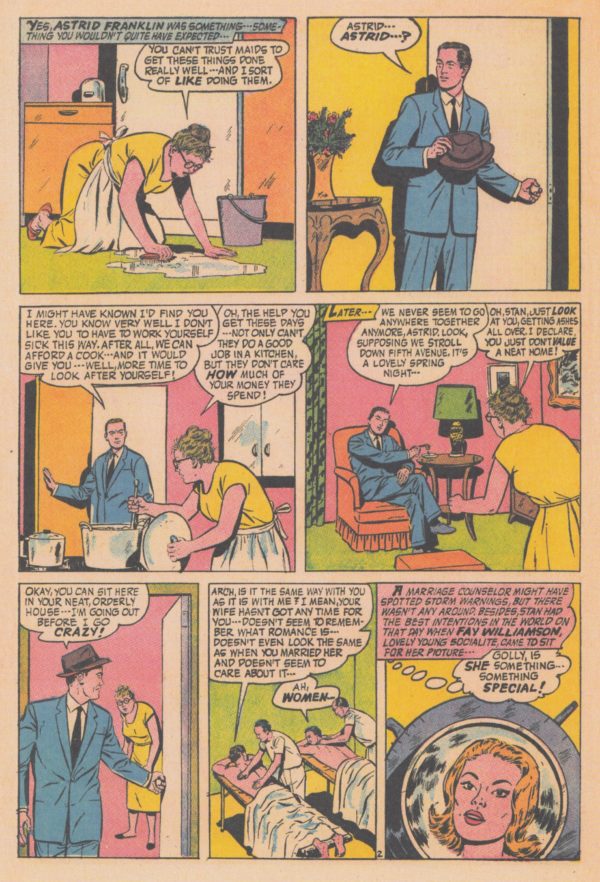

The title story is typical of the collection. It follows Astrid, a somewhat homely, overzealous housekeeper married to glamor photographer Stan Franklin. Stan develops a repulsion for what his wife has become and goes to live out his glamor fantasies with another woman. Astrid, determined to get back what she considers hers, goes to judgemental plastic surgeon Dr. Carewe, who assures her she’s too mentally unbalanced to undergo the knife, and on top of that, she just does everything wrong. He has other means to turn things around for her.

Astrid’s journey transforms into a grandstanding Doris Day-informed sex comedy once another glamor boy is introduced, wealthy playboy Gary King, who is nearly indistinguishable from Stan Franklin. A competition for the Astrid’s affections begins once Stan gets a good look at the new and improved Astrid, and soon enough, the couples are sorted out, each man with their proper trophy wife.

You could argue that the main plot point of the title story isn’t much different than every episode of Queer Eye. The argument is that people settle into their misery and let themselves go, forget to present themselves to other people and not just let their appearance slide into a reflection of their own apathy. The Fab Five are just spreading that news that you can’t stop trying, and that’s not much different than what Dr. Carew is saying, they just say it in a kinder way.

Beyond the makeover aspect, that’s the blueprint for many of the stories in Return to Romance, which are typically epic in quality, covering in about eight pages what graphic novels now need about 200 to depict. And in those eight pages, Whitney is able to inject twists and turns brought about by fate, hubris, wandering eyes, fickle hearts, disagreeable temperaments, and a woman’s inability to live up to what a man wants — though in Whitney’s defense, there are at least a couple stories where it’s the man who can’t live up to what a woman wants.

But the scopes of the stories are remarkable. “The Red-Haired Boy and the Pug-Nosed Girl” takes the reader from childhood on through grad school and beyond as Nancy Wilson, an accomplished scientist researching radioactive isotopes, goes through life with a hatred of red-haired men because of the red-haired boy who picked on her as a kid.

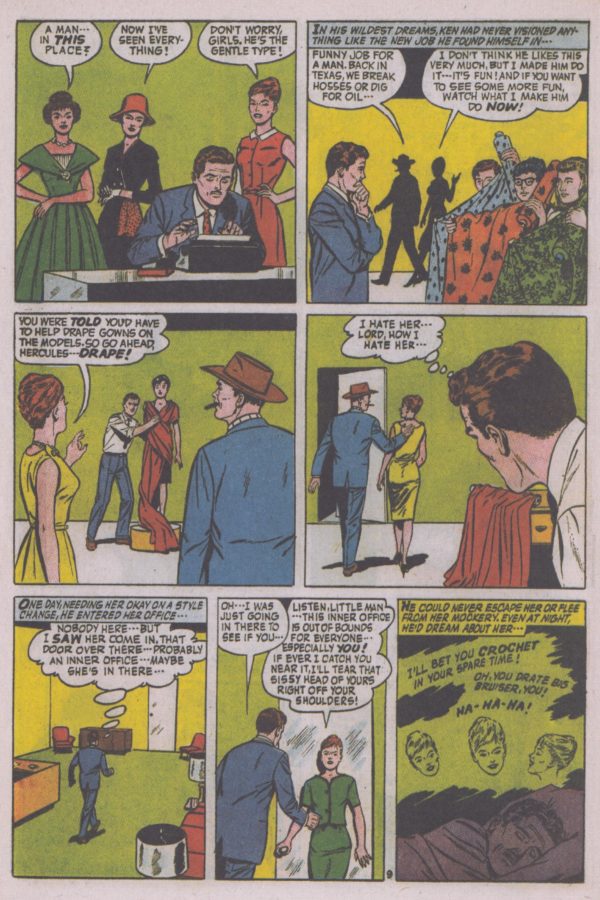

“I Want a Real Man” starts with high school and follows Ken Harrison through his life, from boxing ring to a later period of disgrace. Gender role reversal becomes part of the mix here as Ken goes on his quest to reclaim his manhood, but not without bullying and abuse lobbed at him by a woman. It gives some disturbing insight to how people viewed the role of men back then, but doesn’t sway in its assertion, like all the other stories in the collection, that love conquers all.

“It’s Never Too Late to Love” is a real life-spanning work, following Meg from her self-pitying childhood well into her successful adult years when, after a number of tragedies, she adopts her orphaned niece and manages to create her own competition. This story is decades in the making, and once again presents the man as a witless, helpless trophy, a pawn in a larger game he is not privy to.

Meg’s experience is typical for many of the women in Return to Romance, in which their best attributes are always their undoing in the romance department, and we wouldn’t want any of them to remain single, would we? In “Courage and Kisses,” Jean Latimer breaks free of the shadow of her millionaire father by becoming a fearless daredevil, but of course this creates a life of loneliness for her that results in humiliation stemming from her attempt to prove her strength. “Hard-Hearted Hannah” presents scrappy Hannah Hardy, raised in poverty and using an unexpected inheritance to create a business and better herself, though she is scorned by everyone, including the narrator, for having cold business sense, which she has to dispense of for a man.

There’s not much to recommend Elsa Norton, though. In “The Guy You Love” she goes through a detailed accounting of her love life with her old friend Leona, mostly a reason to talk about Jerry Fielding, the guy with big dreams, no funds, and whole lot of bullshit. He strings Elsa along, Elsa constantly makes excuses for him. I don’t know about you, but the entire time I was reading it, I kept thinking to myself, yeah, I’ve known a few Elsa’s in my life, which made my eyes roll at the fairy tale conclusion. On one hand, Whitney is being admirable here, suggesting women shouldn’t choose partners solely on economic matters, but in the end, he has it both ways.

But it’s not always about men knowing best, and “Beat Romance” is an early work of girl power. Dr. Benjamin Winters is a stuffed shirt academic returning to America for the first time since childhood and he’s fallen victim to some scare-mongering about American teenagers. Of course he finds himself saddled with entertaining the teenage daughter of a colleague and of course all his nightmares come true. But Cindy Lamb, the daughter, is going to win this round by putting chauvanism and toxic paternalism on display.

The message in “Beat Romance” becomes strangely subversive thanks to Cindy — something about women being perfectly capable of solid achievements having to contend with men refusing to believe that’s possible and treating them like animals that need taming. But that still doesn’t mean that love doesn’t conquer all.

Margie Tucker pulls her own Cindy Lamb in “The Brainless One,” where Margie introduces herself by saying, “I’ve never been one for heavy thinking.” No worries, Margie, neither have many of the other characters in the book. Margie has her sights set on Dr. Joel Bentley, who is in town to set-up a rocket engine factory and needs a place to stay. Well, Margie can cook and she wows Bentley with that talent, but when an old flame shows up to divert Bentley, Margie has to show him what country gals are made of in order to win his heart. I believe the lesson here is that she might not have a brain, but Margie is all heart.

It’s hard to say if all readers will take away what Nadel and Santoro do from Whitney’s work, since that might require distinguishing it in thematic terms from other romance comics of the era and attaching concepts that are probably more unintended, unconscious results of the work as Whitney created them. But you don’t actually need any of that to enjoy Return to Romance. One thing that separates Whitney from a lot of romance comics of the time is that his are eminently readable, and the sprawling quality of their scopes make them mini-epics that could be Vincente Minnelli movies without a problem.

But maybe it’s Liana Finck, who wrote the Introduction, who captures it best as she cuts through the obvious dated aspects of the stories which scream sexism and gets to the center of them by proclaiming them as fairy tales from a twisted era. “I find them touching and empowering and human,” she writes. So do I. And Cindy Lamb is one of my new heroes.

Comments are closed.