Since 2015 Liana Finck has been a rising star in her role as a New Yorker cartoonist thanks to her singular presentation and sensibility, but also thanks to a boost that most cartoonists never get. Finck was a prominent figure in the documentary Very Semi-Serious, which captured the cartoon department at the magazine just at the point Finck began pursuing work there. It gave readers a rare insight into the person behind the cartoons before they had really encountered the work and that’s given Finck an unusual relationship with her audience. It’s often very personal, very familiar.

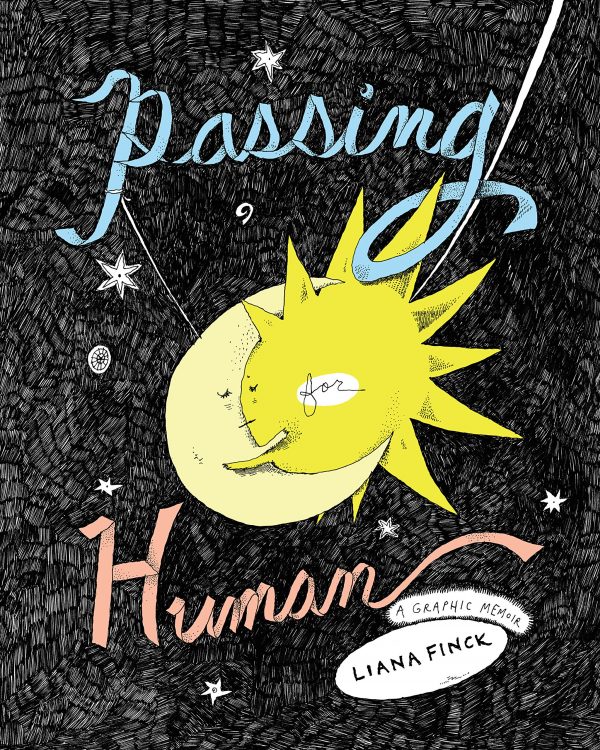

Finck’s second graphic novel, the autobiographical Passing For Human, was released this year to resoundingly positive reviews. She has also found a successful personal outlet with Instagram, where over 200,000 followers find powerful meaning in her off the cuff minimalist cartoons that analyze her own psychology and general human dynamics, as well as push back strongly against misogyny directly and bravely.

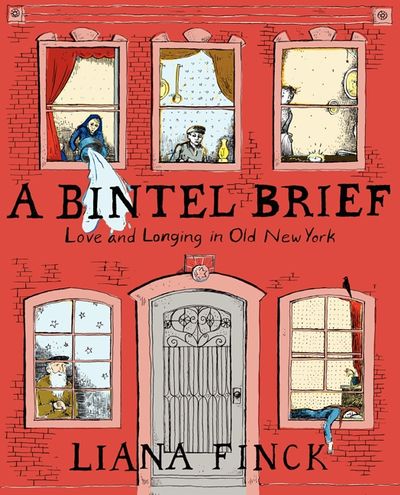

Finck’s first graphic novel was A Bintel Brief, published in 2014. She currently lives and works in Brooklyn.

___________________________________________________________________

I do parse it in conversation, but I guess I’m alone a lot so I think I draw as a way to get my feelings out when I’m not with people. But I guess I do that more with the Instagram drawings.

I talk about everything. I just don’t solve things. When I talk it’s more circular. I don’t really believe talking solves things, but I do think talking make things real. I think drawing solves things but talking, you feel less crazy when you talk about stuff. It helps you with what’s bothering you. I don’t know. I guess most of my friends, we’ve talked about relationships and things we’re annoyed with at work, our families. It’s all about feelings and personal relationships. I think that’s what interests me, but I find that if I draw something once, I don’t need to draw it again, which is not the case with talking.

The book was six years in the making. What did you do in those six years? Was it the work itself that took the time for you, or was it organizing all that emotion and information and process of starting and stopping the work as you did?

I did a million different drafts of it. Like those first chapters were all supposed to be a draft of the book. I mean they are also a different beginning of the book. They really were first chapters and there are other ones that didn’t make it into the book.

I would start the book. I would not know how to keep going with it and would start over. I think it came from low self-esteem. Low self-confidence. And being pretty new as a comics artist and not really knowing how to find the right story and how to express myself in this format. I didn’t even know it was going to be a memoir at first. I think in the future if I make a story, I want to know what it is before I start, but I just desperately needed to work on something and I wasn’t really able to know what I was working on.

So in its earliest phase, what was it for you? What parts were you focusing on?

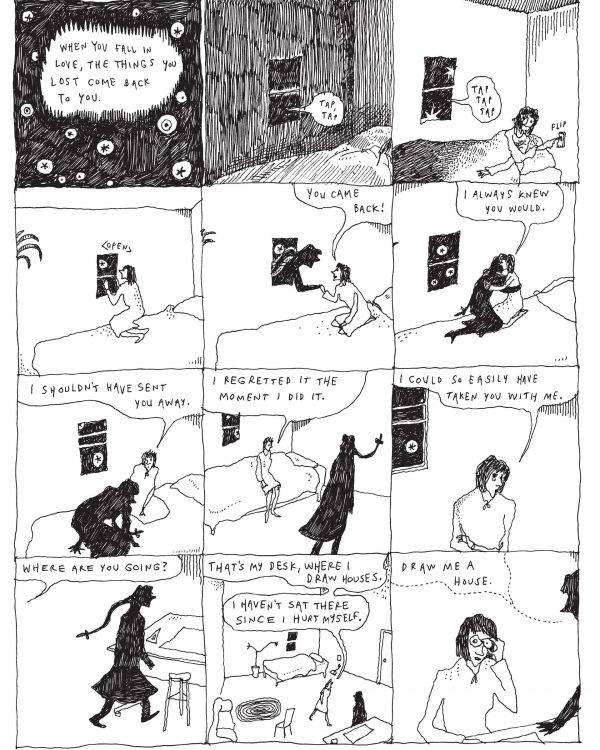

In the earliest phase it was supposed to be an adaptation of a Nabokov novel called The Real Life of Sebastian Knight and in this case, it was a fictional adaptation of that. And then one of the two characters turned into a shadow and the other character became kind of like me, but that made sense because I think The Real Life of Sebastian Knight was pretty autobiographical too. So I was just trying to imitate Nabokov.

The very last part of A Bintel Brief that I wrote was this story connecting all of the adaptations of the letters, which are Yiddish advice column letters that I adapted into comic format. I needed to connect them all in order for the book to seem complete to the publishers. I did a kind of autobiographical-like fictionalized story connecting everything with this ghost character. And I think that’s when I realized that my favorite thing to write is about my life, but with some fictional things thrown in. I think that’s a good thing to do with comics because I think the line between fiction and truth is blurred in comics in a way that it is isn’t in writing because in writing with magical realism it’s really obvious that you’re lying. In a comic, you could just like draw a ghost there and you don’t need to explain why it’s there. It’s a lot simpler and less involved

And you could take the shadow a lot of ways though I know in the book it’s specifically applied to generations of women.

The way I describe in the book is that women are born with a living shadow and the shadow’s job is to guide you to be yourself and men aren’t born with living shadows because society isn’t trying to keep them from being themselves. As you grow up, your shadow usually disappears because the powers of the society are too strong for it and you lose yourself. In the book, I do describe the story of my mom’s shadow and a little bit my grandma’s shadow, and my shadow, and it’s a story about these quiet stories women pass on from generation to generation. It’s a thing women do because we aren’t historically the writers or the artists, so our stories are more personal and quieter.

Do you know other people whose story you view the same way?

Yeah, I think this is a story that’s common to all women in my opinion.

And it’s obvious you’re interested in the concept of how motherhood affects that story.

Yeah. I write about how if a man feels a calling to be an artist he’s been pushed since the time he was a kid to filter everything, all his being, into making a mark on the world. But at least in my mom’s generation and earlier women were pushed by society to channel everything in their being into being a good mom and a good wife and making a smaller world for their family. So in part of the book, I write my mom’s story and it’s about the division between her wanting to channel her art into a career as an architect and wanting to save it for making this beautiful world for her family.

I think I put her forth as a different model of artists. She quits her fancy career and she designs this incredible house that no sees except our family. She makes this beautiful life for us and she also spent a lot of her time everyday painting. So she does become a painter and that’s a much purer art form than she would have had if she becomes an architect. But she doesn’t have the career that we’ve been trained to think of as the crowning achievement of being a great artist. And I think she feels divided about that.

I can see just from my own personal experience with women in my life and family exactly that dynamic, where women had a certain kind of life before they got married, but they gave up that life for the marriage, especially in the generation before me. Do you see it as generally better comparatively from your grandmother’s generation? Like society has gotten somewhat better at encouraging and accepting women living their own lives?

I don’t know about society as a whole, but I think I have much more of a chance than my mom had and definitely more than my grandmother had. Not that my grandma would have wanted to be an artist, but I think she would have loved to be a lawyer or something. She was so smart. And so pushy. And she was so bored. She invented this illness. Well, maybe it was real, but she spent a lot of time in bed.

It’s interesting how you include your father in the narrative because it seems to me like you struggled a little bit with his oddness, whether it’s valid oddness or something he just thinks he has.

The book is divided into different chapters and the premise is that I lost my shadow and I’m trying to figure out how I lost her and how I can get her back. I keep starting chapters over because I keep trying a different tactic and realizing it’s bombastic and dishonest. So in one chapter, I start with my mom and I say I lost my shadow because all girls lose their shadows so I’m curious how my mom lost hers and it’s this whole tragedy. She didn’t want me to lose mine and then I did. And then I start over and I tell the story of my dad and how my dad is this person who is weird in ways that there isn’t any language for. As a kid, he learned to hide his weirdness and he erases himself in order to fit in with society.

And then he passes that on to me and he’s devastated when he realizes it. I do the same thing and I erase my weirdness and that’s how I lose my shadow because my weirdness and my drawings are my real self. I realized that they’re what makes me different from other people and I just stopped doing the things that make me “me” in order to have friends. But I do struggle with saying that about my dad. I do identify as weird. I don’t really have language for what it is. Like there have been times when I identify as neurodiverse or with mild autism or something, and times when I don’t, but I don’t like to pin that on my dad. My dad doesn’t really act weird. I have a hunch that he shares some neurological differences with me and he’s just learned to really hide it, but also I might just projecting on him. He certainly doesn’t need that language.

He doesn’t need this story and I’m just foisting it on him and I think I would have preferred to write about I think there’s an equivalence of how society’s narrative that women should be artists and mothers keeps women from making careers as an artist. I think there’s a really similar thing with men, how society’s narrative is that a man needs to be responsible and a breadwinner and that keeps men from being artists. I feel like I own this story of artists and I’m allowed to tell it, but my dad, I really don’t think my dad is an artist and I don’t think I own his story and it felt weird telling it.

You do really capture something about men of a certain type that I found really insightful — guys who don’t quite fit in with men’s culture, guys who feel alienated by it or maybe like they exist on the edges of it. As you said, there’s no language for that.

I was telling the story about how men suffer from society’s story about men. My dad’s weirdness could just mean that he has a personality and society thinks of men as these impersonal gods and he’s, he’s like, oh no, I’m not that. I’m not this impersonal guy in a suit who makes everything okay. So I must be really messed up somehow and I need to hide my real self.

I think a movement of women coming forward and saying we’re not what society says we are should also be a men’s movement. I wish men would be evaluating themselves. I see a lot of defensiveness in the bad men and a lot of ‘I’m not going to talk about myself, let’s only talk about women’ in the good men and that’s kind of a shame.

Part of what’s being asked nowadays is for men to stop talking and start listening to women more, undeniably a good thing. But they also need to look at themselves critically and maybe offer less advice?

I don’t know if I believe that about people shutting up and listening. Shouldn’t that go with the territory of the minorities and the less privileged people talking? I think it should be about people talking and not about telling other people to shut up.

Right. I guess my thought is that sometimes — and who knows, maybe I’m doing it right now in this interview — men, when they have a dialogue with women, tend to talk over them, right? So isn’t that why men should talk less, listen more?

With the Kavanaugh hearings, there was this political cartoon that came out of Lady Justice having a Republican arm shoot out and cover her mouth and push her down. The cartoon was by a man and I thought it was really powerful, but I’ve been seeing all these women posting the cartoon was saying like, this is what happens when we let men talk about our problems. Like we should be talking, the men should not be drawing cartoons about it. That seems wrong. I think this is stuff that we all need to grapple with and talk about together.

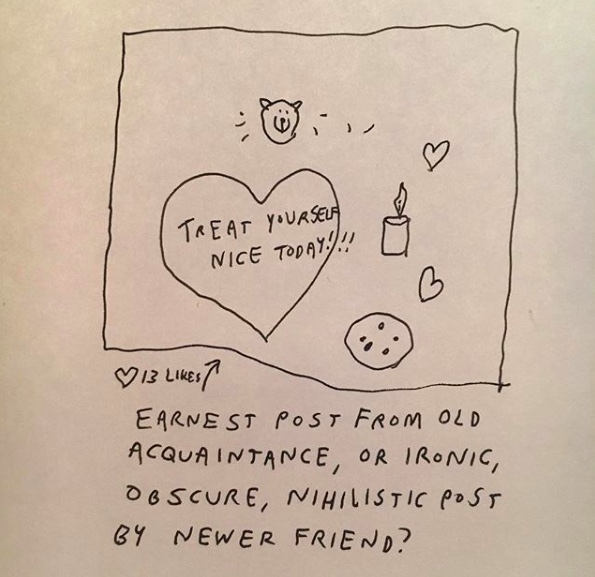

I wanted to ask you about your Instagram work. Some of it’s cartooning as you think of it and then a lot of it is in the form of words and connections, almost like charts and graphs. It feels like we’re looking into your brain as you work things out. Did you do that kind of thing before Instagram?

No. I like having an audience. I don’t think I ever work when I don’t have an audience, which is one of my great failings.

I love reading the reactions to them. There’s a lot, “holy crap, I thought that but I’ve never been able to express it and now you’ve put it into terms that I could show someone to explain my thoughts.”

Sometimes I agree with them and sometimes I don’t. Sometimes I just put things on Instagram and I don’t really know what they are. I just want to give people something and I don’t know, but often I’m working out something. I’m dealing with it and putting it into a diagram so I can understand it and stop being anxious about it.

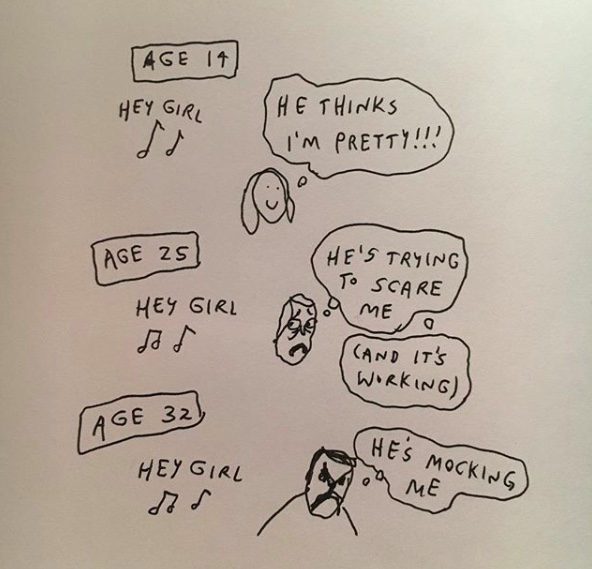

I’m surprised that people relate to my stuff. I always thought of myself as not that relatable and maybe in person I’m not that relatable, but it warms my heart that people can relate. I think I make things universal mostly because I don’t want to talk about people in my life in personal ways. Even though I’m a very autobiographical artist I have a pretty strong moral compass about not oversharing about people I know. Also, I’m not interested in details. I’m interested in the power structure and some strong feelings tend to be pretty universal.

You address misogyny and the behavior of men quite often in the Instagram work. Have you ever been targeted online by Comicsgate types?

On the one hand, I guess I’m liberal enough that right-wing people don’t even read my stuff so they don’t troll me. On the other hand, I’m not the most extreme liberal. I believe in #metoo strongly but I also question #metoo which a lot of my friends don’t do. And I’m willing to make fun of women who are Park Slope moms and so proud of breastfeeding that it’s annoying. Not that I’m anti-breastfeeding in public, I’m so pro, of course, but because of this most of my trolls are actually super liberal women and not right-wing men, which is a lovely kind of troll to have. It’s fine.

I once called Trump a sociopath in a comic and it wasn’t even a very angry comic. I just threw the word out and I got all these angry emails from this whole group of people who self-identify as a sociopath and were like, don’t use that as a slur. And I was like, oh, okay. And that really hurt my feelings but I felt so bad that I hurt them.

But I’ve never been trolled by people who are like, “no, Trump’s not a sociopath, he’s awesome.” A lot of my friends have been trolled by the men in the comics world. I’m not proud of this, but I have nothing against R. Crumb and I love his work. I have some things against R. Crumb, but I love his work and a lot of my friends are hurt by my stance on R. Crumb.

Isn’t that the ideal, though, sort of an acknowledgment of the objections of others while still having your personal opinion? You recognize the issues with Crumb as legitimate, but also have your own view on them.

We’re living in a time of war — I mean a social war — and it’s not the best time for freedom of opinion I don’t think. And I get that. Like I have trouble having friends now who think Kavanaugh should be on the Supreme Court, for example. And that’s a valid opinion, but this is not the time to have that opinion and, and it’s not the time for me to be open to those people. Which is a shame because being open is the thing that makes us human, I think.

Great interview.

Comments are closed.