Qualification

By David Heatley

Pantheon Books

We all end up like our parents. I know for some people that’s hard to hear, but I’ve seen it to be pretty true across the board and I have no clue if it’s nature or nurture, or if that even matters. For others, that might be good news, and for still another section of folks, there’s bound to be some denial since much like 21st Century American Fascism, it doesn’t always look exactly like the way you’ve been traditionally seeing it, so you don’t recognize it at first.

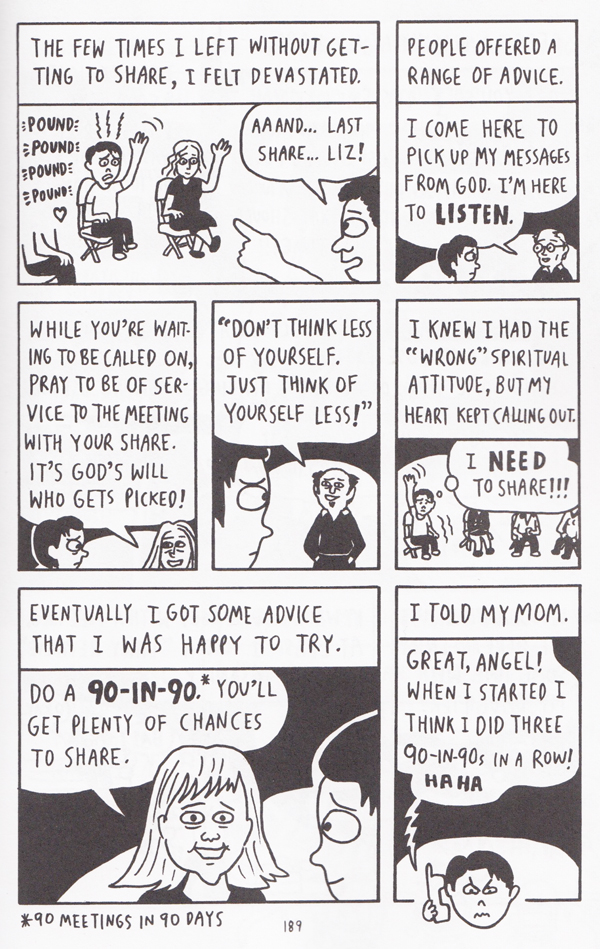

Couple that with another truth about humans — the one thing we all have in common is that we all want to be seen and heard. It’s true whether you’re a hardcore conservative demanding the world suck it up or a liberal snowflake who over-absorbs the hurt of others, whether you’re someone of privilege or marginilization. We want our views and experiences to be acknowledged and considered, regardless of the content or substance, and this need can lead to the most unlikely thing becoming addictive — human contact.

Much of that and more is covered in David Heatley’s Qualification, marketed as a memoir of being addicted to 12-step programs, but more an examination of the emotional maze that dominates the human experience and how every turn we make in that maze has something with the potential to send us further off from our original plan, even as it convinces us the goal has remained the same — finding happiness. It also confirms that when people group together to speak openly and intimately about their problems, things are bound to get weird. And awkward.

In 12 step programs a qualification is essentially a monologue by a meeting member where they explain their addiction, hence the title to Heatley’s memoir. From an outsider perspective you could also look at a qualification as a confession of guilt and as dizzying psychological pinata of lurid details. If you like slowing down for car accident sites, spying on neighbors, or reading celebrity gossip, then listening to qualifications is probably up your alley. If Heatley’s presentation of them — and their manifestation as a memoir — is even remotely accurate, they are filled with too much information.

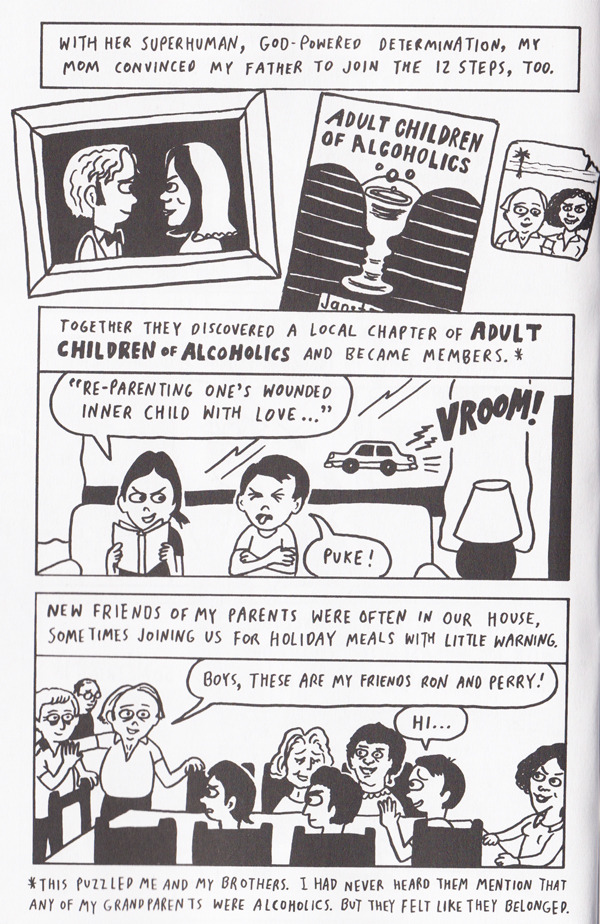

When we meet Heatley’s family, it’s helmed by two adults who give themselves over to 12-step programs and allow them, along with an affiliated church experience, to engulf their family life, which makes the parents’ behavior sometimes creepy and always something that’s easy to rebel against. As Heatley’s parents don’t actually solve their dysfunctional behavior through these programs, but rather change the flavor of them, making the process into a cure with no end. Their solution to their sons’ problems are to try and wrap them into these programs, and when that fails, they appear helpless.

Heatley spends a good portion of his young life rejecting 12-step programs because of his parents, and the first half of the book chronicles the family dramas, some of them truly overwhelming, like his brother’s frightening struggles with mental illness. As for Heatley, professional dissatisfaction and struggles were surmounted by money issues and some personal behavior that he felt he had little control over, all of which affected his relationship with his wife. As everything spiralled together, Heatley felt he had little control over them and inadequate faculties to figure out any solutions.

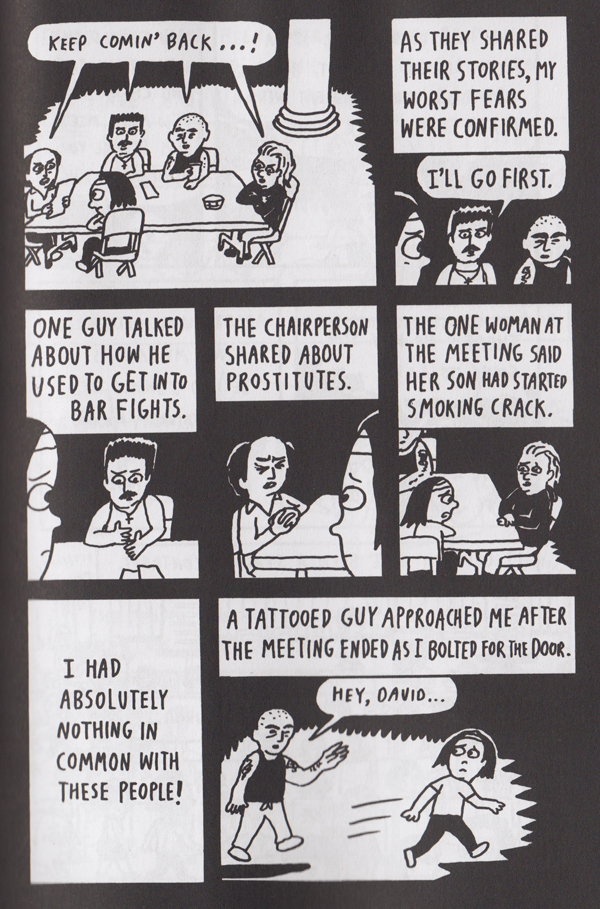

The turning point came when his mother handed him literature about Debtors Anonymous, in which he sees his own story and decides to find a meeting in hopes of getting help. His first impressions hearken back to his attitude as a teen — he’s filled with disdain. Soon enough in the meeting he gets to speak, and that’s the moment it all begins to turn around and Heatley begins a years-long journey though several 12-step programs, some of which he doesn’t even have the specific problem the program is designed to address.

As Heatley traverses these groups, he begins to appear like a junkie needing a fix, the fix being a feeling of elation that participation in the groups often bring. In other words, the heightened attention you are given and the extreme emotion that is directed to you, it all brings a continual head rush that he finds he doesn’t get at home. And the more his 12-step obsession stirs up animosity with his wife, the more he clings to it as the solution to all his problems.

At the same time, Heatley’s experience is as if he is clinging to a pendulum, where one moment he’s dedicated, and then some level of doubt creeps in. The doubt takes the form of dissatisfaction that recovery never happens — it’s a continual process, a treadmill you don’t step off of, and it becomes hard for him to measure whether he is achieving anything. When your distance is infinity, it’s impossible to qualify how far you’ve come, especially when immersed in a universe that tells you that you are powerless against your addictions and that you need the group for permanent bolstering in that powerlessness.

But despite all the talk of community and its importance, Heatley’s experience is a dizzying flow of people moving in and out of his life, with little consistency over periods of time. He will latch onto a group or a person and then move on to repeat. I noticed that this is most likely to happen once he would reach a point of achievement, a level of prominence, where it was harder to define himself as a victim despite his avowals that he certainly was. But victimhood is the currency of that culture and when you run out of cash, you have to figure out a hustle to get some more. And so he would move onto the next situation.

Qualification is one of the most exhausting graphic novels I have ever read. At times, it’s like being Heatley’s roommate — or worse, being trapped inside his skin. That speaks to his skill, but also the thorough quality of the book. This isn’t a skim through the 12-step lifestyle, this is a deep dive and a fascinating one — but in being that, it’s also very emotional. Heatley is incredibly transparent about embarrassing aspects of his behavior and also heinous aspects, all of which serve the point he is trying to make, but also help with the reason he no doubt wrote this particular book.

By the end of Qualification, he’s come to understand what I said at the beginning of this review and has embraced ways to address those without jumping on a treadmill that overtakes his life, feeds on his weaknesses, and threatens to cut off the one healthy connection he has in the world — his wife and his children. They’re the real heroes of this book, as I know Heatley will attest.