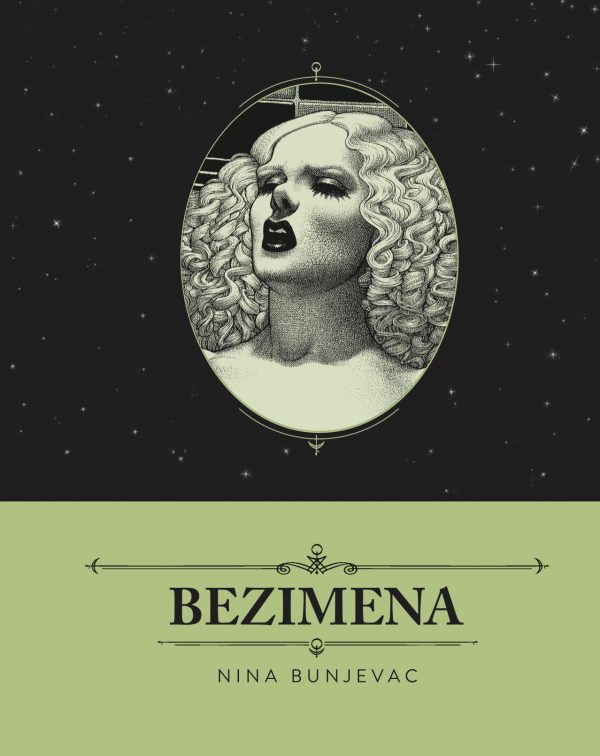

Bezimena

By Nina Bunjevac

Fantagraphics Books

If you have read Nina Bunjevac’s excellent 2015 graphic memoir Fatherland, then already know the darkness and trauma that worked its way through her childhood and culminated in horrible revelations in adulthood. Bunjevac was partially raised in Yugoslavia with communism in full swing and had to bear the burdens of government oppression, but familial tragedy wrought through the brutal political actions of her father. But aside from the memoir aspect, and with family secrets and communist regimes utilized metaphorically as well, Fatherland is really about the limits of perception, how what you can’t see shapes your actions, and how it’s hard to have any control over what you can and cannot see.

Bezimena is a reaction and investigation of other horrible events that happened in those years, several sexual assaults, but not in a direct way. Presented in fairy tale terms, though definitely with a Grimm Brothers joylessness, Bezimena tells the tale of Benny, the son of a leather-maker born to a couple without hope of having children. In fact, he is the cosmic reincarnation of a priestess spurned by her spiritual leader Bezimena because she panics about attacks on their temple. Plunged into a new-life within a generic Eastern European world with an archaic appearance, Benny is heralded as a miracle and raised with the privilege of the blessed.

Stalking the object of his obsession, he comes upon a house in the woods — the story’s most fairy-tale like imagery — with visible invitations to enter and act out the instructions of the soothsaying sketchbook as a beneficial action to all parties involved, something agreed upon and invited. It is not, and this is the result of a lifetime of privilege, a skewed concept of what is beneficial to whom.

As a meditation on sexual violence, Bunjevac’s work is multi-layered and elegant. It refrains from rage but it’s still brutal, both in some of the things she depicts and also in the care she gives to examining the rapist, trying to understand his motivations. For some, this might be hard to accept, but Bunjevac follows up the story with a jarring and insightful afterword that in clear terms talks about the incidents that inspired Bezimena, giving it a context that I think is important.

It’s in this afterword that, I think really displays the difference between Bunjevac and so many other cartoonists, in that her story is mesmerizing and awful and traumatic and, I’m sure, tempting to capture in straightforward terms in the comics form. I think it would be for most people. But Bunjevac is striving for something deeper in this, not just looking at what happened to her and what her specific reaction to it is, but looking at what is happening in the wider picture to so many, looking at the reasons without becoming bogged down in judgement, employing depiction without the slightest hint of endorsement, but more so with a visual understanding of the way cultures interpret such depictions and how they might also feed into the process she is mapping out.

And it is a process. While Benny is undoubtedly a monster, he is one who inhabits a mirage that all of society has fashioned and pushed as “reality.” He is to blame for his crimes and yet blameless for being raised in a sinister mirage that places him at the center, and makes empathy impossible. For men, in particular, the mirage emphasizes self-gratification, and positions other people, particularly women, as tools for that objective.

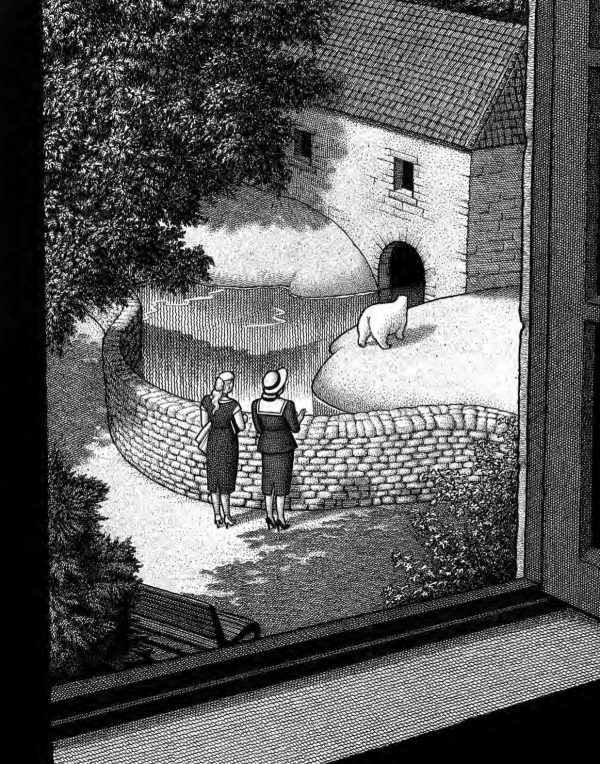

Bunjevac has said that her narrative influence for Bezimena was pulled from classic Greek mythology — particularly the story of Artemis and Siproites, which involves rape and cross-gender punishment — as well as the works of Jean Cocteau and Dennis Potter, and none of that surprises me. Her use of surrealism not as something to differentiate from reality but to define it, combined with the feel of classical themes and literature, really cements it as something apart from so much storytelling I encounter nowadays. Its presentation holds more in common with forms of art films and literature that seem more parts of a bygone era than it does with most graphic novels of any era, and I suppose because of that, and because of its subject matter, it might be too oblique artfully oblique for young, modern readers, since it offers very little through a straight, well-lit shaft that’s clear in its political intentions.

But I don’t know that Bezimena can be read clearly through the political criteria that is the go-to these days. It demands standards for intellectual intake that are less demanding of narrow definitions for art, that accept that sometimes art has to go uncomfortable places and view things from disturbing vantage points to get to the root of what’s important about the subject. It requires a reader to hand over the reins to the work, to refrain from imposing what is considered the right way to approach things and let the work reveal that in this universe, some things are not right. You can change yourself, but the universe is less easy because you can’t change what you are obscured from seeing. The universe lies beyond your own limitations, imperceptible from where you are positioned, and coming to that understanding usually involves a lot of very difficult moments with art.

Bravo Nina!!!

Comments are closed.