In recent years, creators and journalists have shined a brighter light on the intense work conditions required to be a professional comic book artist. Brian Churilla revealed what his days of drawing comics look like, and the picture wasn’t pretty. David Harper wrote an excellent piece titled The Life and Times of the Modern Comic Book Artist that explores the day-to-day experience of drawing comics and the fiscal realities of the profession.

I thought it would be valuable to write something that focuses on one element of making comics in particular: crunch. Crunch is the period of high pressure when workers are expected to get more done, often to the detriment of their own health. In some industries, including comics, the crunch period never ends.

The subject has been on my mind a lot because it’s been a major talking point in the video game industry for the past several years. The tireless reporting of journalists like Kotaku‘s Jason Schrier and Cecilia D’Anastasio has exposed crunch to millions of readers. Sequential artists face similar hardships to video game developers, but the topic is rarely discussed in comics media.

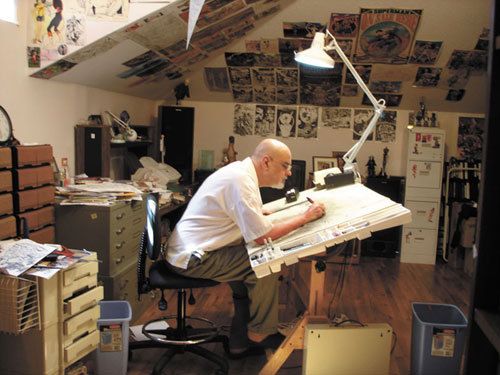

Comic book artists are under pressure to hit their deadlines, but, more importantly, know that whenever they’re not drawing, they’re not earning. They have to produce enough art to make a living off of meager page rates, chaining them to the drawing board. Working such long hours can prove detrimental and even dangerous to artists’ health and personal well-being, but is often a necessity for a career in comics.

Thanks to increased awareness of crunch, video game publishers are starting to be held accountable for endorsing harsh working conditions. The problem is by no means solved, but increased public pressure forces corporations to reconsider their actions and weigh the perceived benefits of crunch against the harm of PR fallout.

Hopefully, the exposure of crunch in comics can start similar conversations and perhaps lead to meaningful change. But the prevalence of comic book crunch isn’t simply the result of toxic company culture. Its roots are deeper than that and, as a result, more difficult to solve.

The causes of comic book crunch

Crunch can take on many different forms. Most reports of video game crunch paint the picture of a studio with a toxic company culture that hands employees deadlines impossible to hit without substantial (and normally unpaid) overtime.

Comic book crunch, on the other hand, revolves almost entirely around income. Games developers at large studios tend to make a relatively good living from their work. But even comic book artists working for top publishers may still live hand to mouth.

Nearly every comic book creator is a freelancer, which means they’re paid for the work they complete, not how long it takes them to finish it. Due to how low page rates are for the amount of time and energy artists put into their work, the economic conditions of the profession are often brutal. Despite the vast amount of skill required to illustrate comics, drawing them is less profitable than most other forms of commercial art.

Multiple artists who I interviewed for this piece expressed that page rates have barely risen over the last 20+ years at Marvel and DC. The rates for drawing indie comics are even bleaker.

The low pay can be attributed at least in part to the size of the direct market. Unlike video games, monthly comics don’t earn hundreds of millions of dollars. They cost more than they used to, but publishers sell less of them. In a market where the best selling title of the month doesn’t always crack 100,000 copies, there’s a ceiling to what publishers can afford to pay creators. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t room for rates to grow.

Jen Bartel, popular cover artist and co-creator of the Image series Blackbird, shared why she believes page rates have stagnated:

I think [the reason the rates are low is] a combination of the arts in general being gradually devalued over the last 5 decades along with the lack of growth and evolution in comic book sales. Average comic book page rates have not increased in any significant way since the ‘80s, and like most creative industries, there are lots of hungry newcomers who are eager to accept low rates for a chance at getting a foot in the door. No one should fault them for that, but it definitely does not encourage companies to be ethical about their rates across the board.

The coveted nature of making comics enables publishers that can afford to offer higher page rates to pay creators less than they deserve.

When page rates stay flat as the cost of living increases, comic book artists face increased economic pressure and more need to crunch. To produce enough art to make a living, they’re forced to the sacrifice their time, their personal lives, and their health.

The effects of comic book crunch

Mike Choi, illustrator of comics for Marvel, DC, and Top Cow, recently returned to drawing comics after several years away, but he knows full well the consequences of the profession. He said that, when forced to work such long hours, creators’ personal relationships suffer, and people even die “of natural causes” (quotations his) relatively young as a result. But Choi accepts it as the reality of drawing comics professionally.

I also spoke to Jim Zub for this piece. In addition to writing comics for publishers including Marvel, Image, and IDW, he was a professor at Seneca College‘s award-winning Animation program, preparing the next generation of artists for a career in the arts. Here’s how Zub described the effects of crunch:

It’s an emotional, physical, and financial toll. You want to deliver your best but also temper that with the reality of being at a drawing board or digital tablet for 8-10 hours a day.

Zub explained why drawing comic books is so challenging and time-intensive:

Comic pages require a ridiculous amount of flexibility and incorporate aspects of design, staging, character and background work, clarity, and composition – all of it cranked out under intense deadlines. Doing that, page after page and month after month, usually for rates that are on the low end for this level of work, leads to a lot of stress and burnout.

Bartel offered the most succinct description of crunch:

It’s truly comparable to running a marathon, and without maintaining a healthy work/life balance, exhaustion is inevitable.

The science is clear: crunch poses serious health risks. TIME and Harvard Health Publishing reported on some of the dangers of overworking. It’s known to cause back and neck pain, increase the risk of medical emergencies including strokes, heart disease, and cancer, and elevate anxiety and depression. Overworking can even compromise your immune system, making workers who crunch more susceptible to catching a cold, the flu, and now COVID-19.

The demands of making comics put creators’ health at greater risk, but the majority of freelancers don’t receive health benefits through an employer. The lack of health care has never been more dangerous than it is now because the physical strain of crunch is compounded when an artist becomes sick but continues working. Freelancers don’t generally receive sick leave, so many creators literally can’t afford to get the rest they need to recover. In 2020, that could literally prove deadly.

The devaluation of artists

The challenges of a career in comics aren’t measured solely by hours at the drawing board. Other stressors include criticism from fans and working for publishers that know (and occasionally remind you) that another artist is always ready to take your place.

Choi explained that making comics puts creators under the “stress of being under a microscope,” trying to satisfy “a company we’d grown up worshiping and/or a rabid and fickle audience that we want to please above so many other things.”

Creators feel like they should appreciate the opportunity to draw the comics they grew up reading, no matter how hard they have to work to do so. Choi said he and other comic book artists are aware at all times of how the lengths aspiring creators would go to for the same opportunity.

[W]e’re almost conditioned to always remember that there is a line of artists behind us who would do our job for free. Every major convention has portfolio reviews from major publishers. Talent scouts fly all around the world looking for competition for our jobs.

Some of the pressure, however, is self-inflicted. Choi doesn’t place the blame for that at the publishers’ feet, but it speaks to the added pressure creators face.

Different things like awards, the glamour of the next big project that you want to win, social media presence and follower count, FOMO, all contribute to why you want to pile on the work, all the way up to the deadline, no matter how much or how little you get paid.

Bartel pointed out that the isolating aspect of making comics makes matters worse.

I think the biggest challenge for so many creators working in comics today is the sense of isolation; monthly comic schedules can force a lot of artists to work long hours all alone without any additional social interaction, and that creates an environment where they’re more likely to recede into themselves and become disconnected or even depressed.

The stress of such time-intensive work is aggravated by the lack of opportunity to socialize and connect with others. Some artists rent shared studios, but most work alone. Thousands of Americans are experiencing what it’s like to work from home for the first time during the outbreak of COVID-19. For most comic book creators, it’s long been a way of life.

Scheduling and lead time

Publishers can take measures to improve artists’ working conditions other than raising wages. One potential way to mitigate the effects of crunch would be more flexible scheduling. Several of the creators I interviewed for this piece brought up the topic, though opinions were mixed on how much it would help.

Zub explained how little lead time creators are given in comics compared to the book industry.

For my comic editor [a] 3-4 month sprint is standard operating procedure while my prose editor feels like we’re cutting things close with a 12-month lead.

But, no matter what changes publishers make to scheduling, Choi believes that crunch will always exist in comics.

The problem is that the grind is just an inevitable part of the job for so many of us, in my opinion. The only thing I can think of beyond that is to pay us more. But aside from the fact that rates haven’t gone up since before the turn of the millennium, I genuinely think that many of us would still put in the same hours, but perhaps we’d do less books over a career.

Bartel acknowledged that more lead time can help, but said it ultimately comes back around to page rates.

Giving artists more breathing room in the schedule can be a huge help, but ultimately if artists aren’t getting paid a survivable rate (once it’s broken down hourly) from these jobs, they are forced to take on more work, so just increasing the timeline doesn’t always mean that the artist will be working less—It just means that they’ll have to supplement their main job with additional jobs to make ends meet… so…. the thing all companies can do to prevent their employees from overworking and burning out is: pay living wages.

One thing more lead time does accomplish, though, is to make creators feel valued, as Zub pointed out.

Artists need time to produce their best. They need to know that they’re an absolutely integral part of a project and be brought in as early as possible. When an editor throws a bunch of artists (or inkers or colorists or letterers) at a project at the last minute, they can’t help but feel like they’re a commodity, widgets being pushed around to fill gaps instead of crucial collaborators producing something worthy of their time and skill.

The value of time management

After considering what publishers can do differently, the question becomes what comic book artists can do to reduce the need to crunch. One of the most valuable ways to do that is to learn how to better manage their time. With the right systems in place, artists can increase output so they can get more done in less time.

Over the course of CHEW’s run from 2009 to 2016, Rob Guillory learned how to set a reasonable schedule for himself so that he could stay consistent without having to regularly endure comic book crunch. He has advice for new artists on how to avoid burnout:

Learn your limits and work a schedule that fits within those limits. Back when I was adjusting to a monthly CHEW schedule, I had to figure out how much work I could realistically do in a given week without killing myself. For me, that meant working a five-week-per-issue schedule.

He said to watch for warning signs that signal you’re heading for a crash

[It’s] important to know personal triggers, hints that rest is needed and whatnot. If you know your natural rhythms, you can play to them, rest when needed and ultimately be more productive in the long run.

Guillory is now writing and drawing Farmhand. He recognized that he has less time to draw now that he has three young kids to care for, so he adjusted accordingly. He decided to release the series in 5-month seasons with 3-month hiatus in between arcs because he knows that’s the schedule he can handle.

I learned that after years of burning myself down to a nub. What good is meeting a monthly deadline if you’re too burnt out afterward to actually enjoy your life?

Above all else, maintaining a healthy lifestyle is essential to Guillory’s continued success.

It’s taken years of trial-and-error to learn that I cannot divide my life into “work life” and “home life” because the two are symbiotic. If things at home are not well, that’ll affect my productivity at work, so I have to make sure my real relationships are healthy before I can focus on creating stories about imaginary people. And that desire to have healthy well-being has led me to focus more on regular exercise and self-care stuff.

By separating his two worlds, Guillory gets the best of both.

It sounds counter-intuitive, but what happens away from my drawing desk is probably more important for my productivity than the moments I’ve got pen in hand, drawing a page.

A lot of people struggle with maintaining a healthy balance when working from home. Artists may want to consider renting studio space to separate their work life from their home life. It’s an added expense but potentially offset by increased productivity or worth the cost simply because of how much it improves their quality of life.

If artists feel pulled towards their work 24-7, they’re never truly relaxing, even though that’s the best way to recharge. Balance is key to staying productive, happy, and healthy.

Additional revenue models

Comic book artists have to squeeze every dollar they can out of their comics work. Even after doing so, they may need a second source of income. A lot of artists take outside art and design gigs to help pay the bills, but there may also be viable options that are still in the realm of comics. The additional revenue models can offset the low financial returns of making comics while allowing creators to put most of their time and effort into their chosen field.

Firstly, artists can sell their original art. That’s not news, of course. In fact, it’s the only way many artists can stay afloat. But it also matters how they sell it.

Commissions are one form of revenue, but they take time away from drawing comics. If artists aren’t comfortable with that, they can instead focus on selling the covers and pages from their comics. Creators can sell their original art independently and retain all the profits, but that requires them to devote time to reviewing orders, answering questions, and sending deliveries. Another option is to partner with a comic book art dealer that will handle things on the back-end and can better promote the creator’s original art for sale.

Creating comic book art digitally has become increasingly popular in recent years, but doing so means missing out on sales of original art. Artists have to determine if the time they save by drawing digitally offsets the lost sales of original art. Some artists who primarily work digitally choose to draw covers and splash pages traditionally since they’re the highest earners.

Another option is merchandising. Jen Bartel is one of the best in the business at marketing and selling non-comics products. While retaining enough time to draw Blackbird at Image and various covers, she sells apparel, prints, pins, and even coloring books through her online store and at conventions. I asked Jen what paths she’d recommend artists take to monetize their work.

If artists have the audience for it, creating and selling art prints + additional merchandise formats can also bring in significant supplemental income, but it is essentially an additional full-time job, and it also does not offer insurance or benefits.

Running an online store and selling at conventions can be very time consuming, so artists may want to partner with a company that will handle that for them. White Squirrel is a small company based near Seattle with “a focus on creators and their customers.” The business works with creators to sell products if they “don’t have the time or brain space to take care of all the details.”

David Harper recently spoke with the owner of White Squirrel, Andrea Demonakos, for his podcast Off Panel. They talked about how creators can make money amidst the outbreak of COVID-19, and discussed additional revenue models including Kickstarter, Patreon, selling comics digitally through Gumroad and itch.io, and much more. The episode is a valuable listen for anyone looking for ways to earn extra income during such unpredictable times.

This subject merits its own longform, but it’s important to mention it in the context of how creators can reduce the need for crunch. For artists struggling to survive off of comics income alone, there are other, comics-adjacent options to explore.

Where that leaves artists

Clearly, making comics your career is extremely challenging, and sometimes even dangerous. That’s especially true if artists jump headfirst into comics before they’re earning what they need to. That’s how artists can find themselves facing severe, endless comic book crunch. Bartel stressed that there’s no shame in having a day job before going into comics full-time. In fact, it’s oftentimes the wiser decision.

As a person who worked a day job for many years after graduating from college and even while I was first starting to freelance, I honestly think taking on a part-time or even full-time day job is a great way to bring in steady income AND give yourself the negotiating power to say no to freelance jobs that aren’t going to benefit your career long term. A lot of day jobs will also teach you a ton of practical skills that get utilized constantly as a freelancer, so even though my end goal was to become a full-time freelance artist, I was very glad to have spent 6+ years at full-time day jobs before that happened.

Zub tells his animation students about the sometimes harsh realities of a creative profession and hopes they take it to heart.

We try to prepare students for the kind of hours required and time management skills they’ll need to navigate big projects and intense deadlines, but no matter how much you explain and demonstrate that in a school environment, once they graduate and do it for ‘real’, it’s always a challenge.

When you’re young, you think you can do anything. And maybe you can, while you remain young. But for comics to be a lifelong profession, illustrators regularly have to make sacrifices to their health, happiness, and emotional wellbeing.

Artists draw comics for the love of it, but they kill themselves doing it. Something needs to change in this industry. The first step on the road to change is awareness, so hopefully, this piece brings more attention to the hardships associated with the profession. If more people understand how the industry is broken, maybe the comics community can collectively find a way to fix it.

Thanks to Jen Bartel, Mike Choi, Rob Guillory, and Jim Zub for contributing to this piece.

One reason why Jack Kirby quit comics was because spending hours at a drawing board became so physically painful for him as he aged.

There was the case of Gene Day, who died from a heart attack in 1982, at the age of 31. Day reportedly spent marathon stretches at the drawing board, fueled by coffee and cigarettes.

Gene Colan was hospitalized circa 1969 for similar reasons. I don’t know if Colan smoked, but he was guzzling black coffee all day to stay awake and draw. You don’t get much exercise when you’re at a drawing board for 12 hours straight.

“The coveted nature of making comics enables publishers that can afford to offer higher page rates to pay creators less than they deserve.

“When page rates stay flat as the cost of living increases, comic book artists face increased economic pressure and more need to crunch. To produce enough art to make a living, they’re forced to the sacrifice their time, their personal lives, and their health.”

A couple of points, maybe obvious.

Jobs or professions with crunch exist outside the comics industry.

As for flat pay, that’s been a thing of the US’ economy — the greatest economy ever per the current POTUS — starting in the 1970s and never getting better but occasionally worse. Again, not limited to comics.

But related to that, I would looove to know the budgetary breakdown of the cost of publishing the average major publisher book. Spitballing (please someone who knows correct me):

Books cost ~$4/a pop, with ~50% going to the publisher.

Let’s say circulation is ~30k, so the book nets ~$30k for the publisher.

Deduct various overhead, costs like printing, shipping from printer to distributor and the other normal costs of publishing.

No idea what’s leftover after that to divide amongst the creative team but… can’t be much, maybe a decent living at best, nothing great.

OTOH, till the economy got kicked to the ground by the global pandemic Washington had no interest in addressing till forced to*, ~25% of full time workers needed public assistance, easy credit and/or additional employment to make an actual fair wage. God bless if you find that acceptable, but you’re dead wrong. (*We all know that Wall Street’s relationship to the actual economic exists pretty much only as an establishment media storyline, right?)

Comments are closed.