[For #BlackOutTuesday The Beat is reposting content that spotlights black voices and issues – originally posted 8/15/16.]

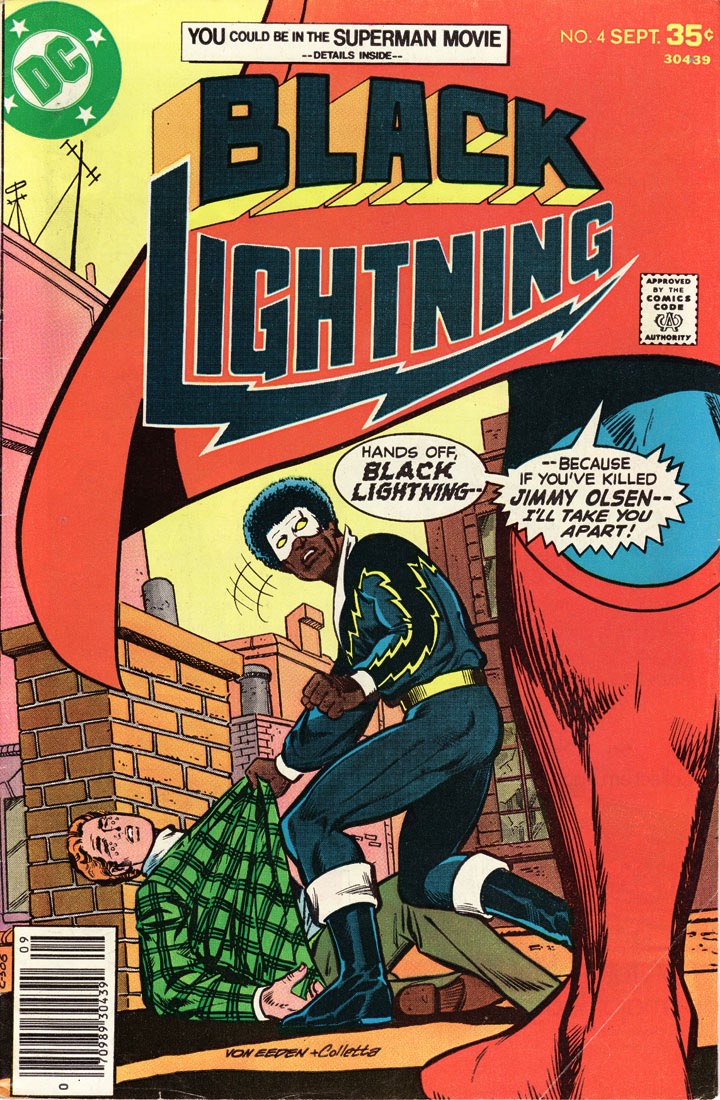

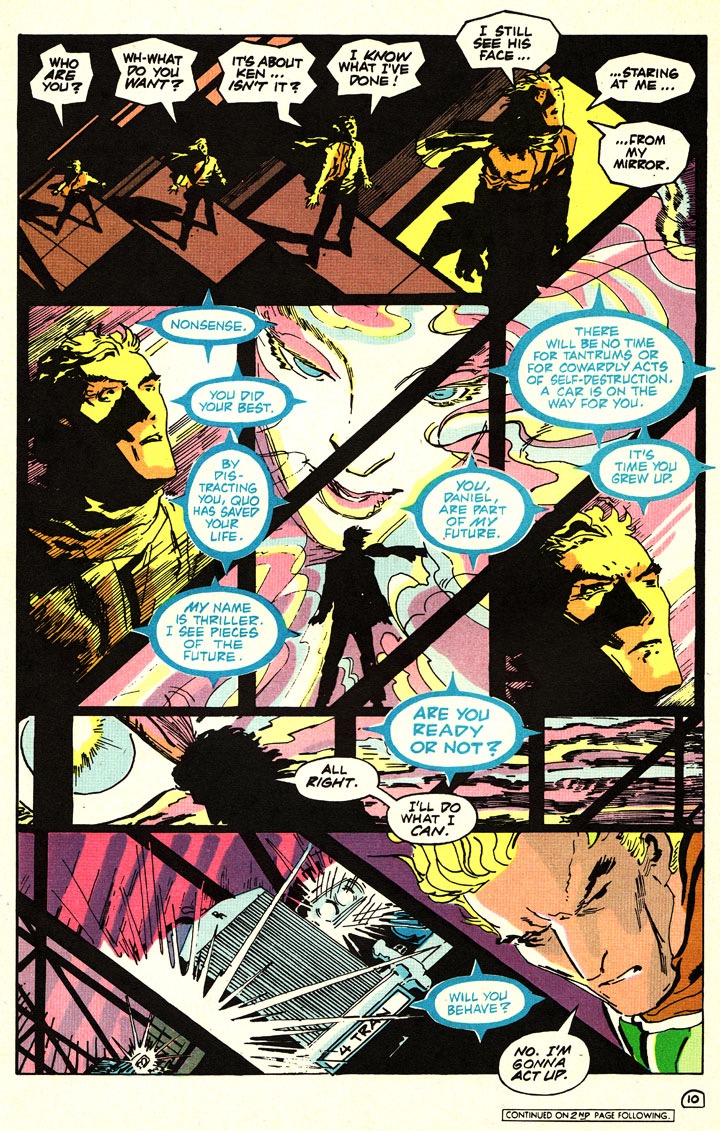

Artist Trevor von Eeden has a secure place in comics history for a couple of reasons. First, he was one of the most distinct and powerful mainstream comics artists of the Bronze Age, with significant work on Black Lightning (which he co-created drew the first appearance of), Black Canary, and perhaps most memorably, the challenging, ahead of its time Thriller, written by Robert Loren Fleming. Much missed Beat contributor (and, oh yeah, Copra creator) Michel Fiffe has a lot of information on Von Eeden in a past Beat post and on his own site.

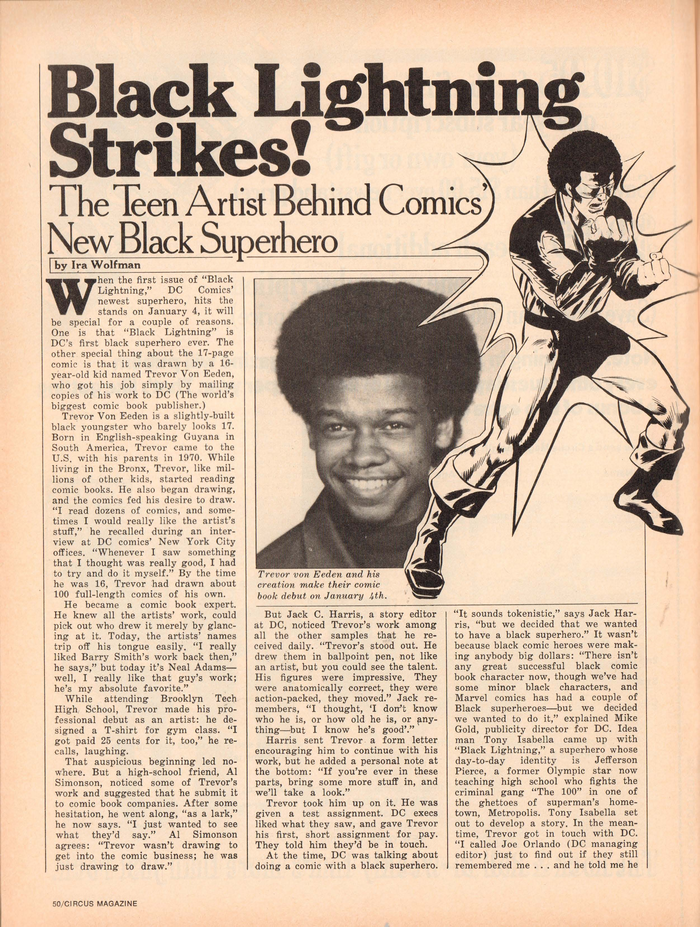

Von Eeden was also known as the “first black comics artist” at DC. I don’t know if that’s accurate or not, but Von Eeden mentioned it several times. He was also hired when he was a teenager, at age 16, to draw comics and while still a teen became the artist on the new book Black Lightning, written by Tony Isabella and the first African American superhero to have his own title.

A teenage, minority creator at a company where people skills weren’t always the greatest. What could possibly go wrong?

Von Eeden has a very very long interview with Ramon Gil where he talks about all the things that went wrong. Von Eeden has had a lot of personal difficulties in his life, many of which, I’m guessing, weren’t primarily caused by working in comics. But I’m also pretty sure that the burden of being a teenaged groundbreaker in an industry that didn’t have a lot of experience with these issues, didn’t help.

As in past interviews, Von Eeden mentions a “Chair prank” which greatly demoralized him.

Unfortunately, the folks at DC Comics chose to play a very mean-spirited and ill-advised “prank” on me, shortly after I’d started drawing the series [Thriller]—one with tremendous repercussions on my life and career. Newbie editor Alan Gold (who took over the editorial chores starting with issue #2) and I were summoned to a meeting to discuss the book (I forget whose office it was)—where there was only one chair available, for only one of us to sit. I refused three invitations to sit down, since there was no way I was going to sit, and have my editor stand around like an uninvited guest in a meeting that concerned us both. Alan then decided to break the ice, and after my third refusal, moved to sit in the chair himself. It collapsed completely to the floor, where he was left sitting flat on his ass, with all four legs of the chair splayed out around him. After a pause of about half a second, he laughed uproariously. However, I didn’t find that joke intended to be played out at my expense the least bit funny—as I said, I took my job very seriously—nor did I find funny the fact that the meeting mysteriously evaporated after that, with no explanation nor apology given about the strangely collapsing chair, and without a single thing about THRILLER being discussed.

I’d spoken to Alan a few years ago via email—and now in his ’70s, he said that he has no memory of what must’ve seemed to him a harmless office prank (although I’ve never, to this day, heard of any other such pranks being played on anyone else at DC Comics.) The effect of that incident on my consciousness, however, was considerably more severe, and long-lasting. The notion that such juvenile, mean-spirited treatment was actually intended for me—literally as my reward for the years of extremely difficult and dedicated effort to give my absolute best to the people who’d given me such a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity—continued to grow and ferment in my subconscious mind, from then on. The quality of my work—which was proportional to the enthusiasm and tremendous gratitude I’d felt at being given such a great chance to actually become an artist in the comics field—began to steadily diminish, with each succeeding day, week, and month spent at my board. I was completely bewildered at the inexplicable treatment that had been intended for me, and became more and more depressed at my complete frustration to even begin to understand what it was I’d done to deserve it.

Von Eeden is a figure of some controversy — his latest work is a graphic novel called The Original Johnson about boxing champion Jack Johnson. There’s a lot about that in the interview, a lot of about some current things that happened, some old history about other comics figures. I don’t offer this link as a suggestion that there is not another side to all of this. But being a pioneer requires a lot of discipline and focus, and not everyone can stand the constant scrutiny and justification for the behavior that called for the need for there to be a pioneer in the first place.