[For #BlackOutTuesday The Beat is reposting content that spotlights black voices and issues – originally posted 01//29/20.]

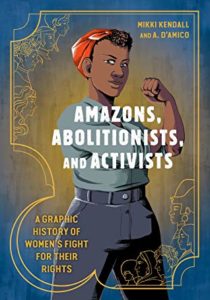

Back in late November, I was able to catch authors Mikki Kendall and N.K. Jemison at Strand Book Store in New York City, where they were talked about Kendall’s new book Amazons, Abolitionists, and Activists: A Graphic History of Women’s Fight for Their Rights.

I was blown away. After the signing, multiple emails, the holiday season and several sick days, I was able to chat with Mikki Kendall and artist Aster D’Amico about their graphic history of Women making moves.

Mikki Kendall: For me, well, first of all, I grew up on comics. I don’t have a single, like, “Oh and then when I was 13” moment. I actually had no idea that people thought girls didn’t read comics until I was a teenager because of X-Men, and all that was always around. At the grocery store, I would get Archie comic books, that kind of stuff.

I thought everybody read comics, and then I hit puberty and started going to comic book shops by myself and was like, oh, okay, that guy. And then I figured out that some stores were better than others. I didn’t think I was going to be able to write comics originally, so much as I thought [the genre] was really cool. I love the genre. And then Gail Simone asked me if I was a writer; I brought her cupcakes at C2E2 and fun fact, if Gail Simone asks you if you’re a writer and you’re a writer, you say yes. When she asks if you have any interest in writing comics, you also say yes. Gail Simone is my fairy comic godmother.

Aster D’Amico: Yeah so this book was actually my first non-anthology and non-self-published book. Mikki and I worked together when I was a student on an anthology where everyone in my class was paired up with a professional comics writer, and we needed to produce a five-page story that we then turned into a physical book that was called Spitball. Other than that, I did a few queer historical anthologies, and then publishing sort of journal comics, stuff like that.

Mikki contacted me about a year and a half after I graduated in 2017, said she had this idea for a sort of sci-fi but also historical recounting of women’s history that she was trying to do, and she wondered if I was interested in participating. Of course I said yeah.

Kendall: It wasn’t fun to me until I got to college. And it’s one of those weird things where, you know, you have those mandatory history classes that you have to kinda take your freshman year of college. I really thought I was just knocking out a requirement. Sure, I’ll take African American history. I know that stuff, it’ll be easy. And I mean, it was easy in the sense that it was interesting and I learned a lot of things and was really into the class, but that was where I first figured out that I actually didn’t know hardly any history. I knew a tiny sliver. I also figured out that history was way more interesting than a list of dates and places.

The Beat: I guess that was part of the impetus for wanting to do Amazons, Abolitionists, and Activists graphically, as opposed to just doing this as a textbook.

Kendall: Yeah, I think for a lot of people who aren’t good readers, history is boring. The way we teach history between kindergarten and 12th grade is really boring. I’m sorry; I know that there’s going to be some teacher somewhere who’ll insist that they’re magic, and they’re not. Maybe that one teacher is, but generally, the way that we teach history is we teach it by rote — the same things in social studies over and over again, year to year. You learn the Constitution — or you should — you learn a list of important American dates and some important European dates.

Then the requirement is over and you really didn’t learn that much about many people except for whoever you were assigned as your very special Black History Month and Women’s History Month project or whatever. You certainly don’t learn about how those people relate to each other. Right? We don’t teach you history like it’s a story, we teach you history like it’s a grocery list, and then we don’t know why you don’t retain it. Do you remember what was on your grocery list three years ago?

The Beat: I can barely remember what I bought at the store the other day.

Kendall: You remember your first really good comic; you remember your favorite bedtime stories. You remember some major event happens, whether it was something tragic, like the Challenger or the Twin Towers, or something good like Obama being elected. You remember those things because of the story of life that’s happening around you. The context is what we are remembering, and then really you kind of remember the imagery better than you remember the words.

The Beat: Aster, what did you want to bring to the book when Mikki asked you to do this?

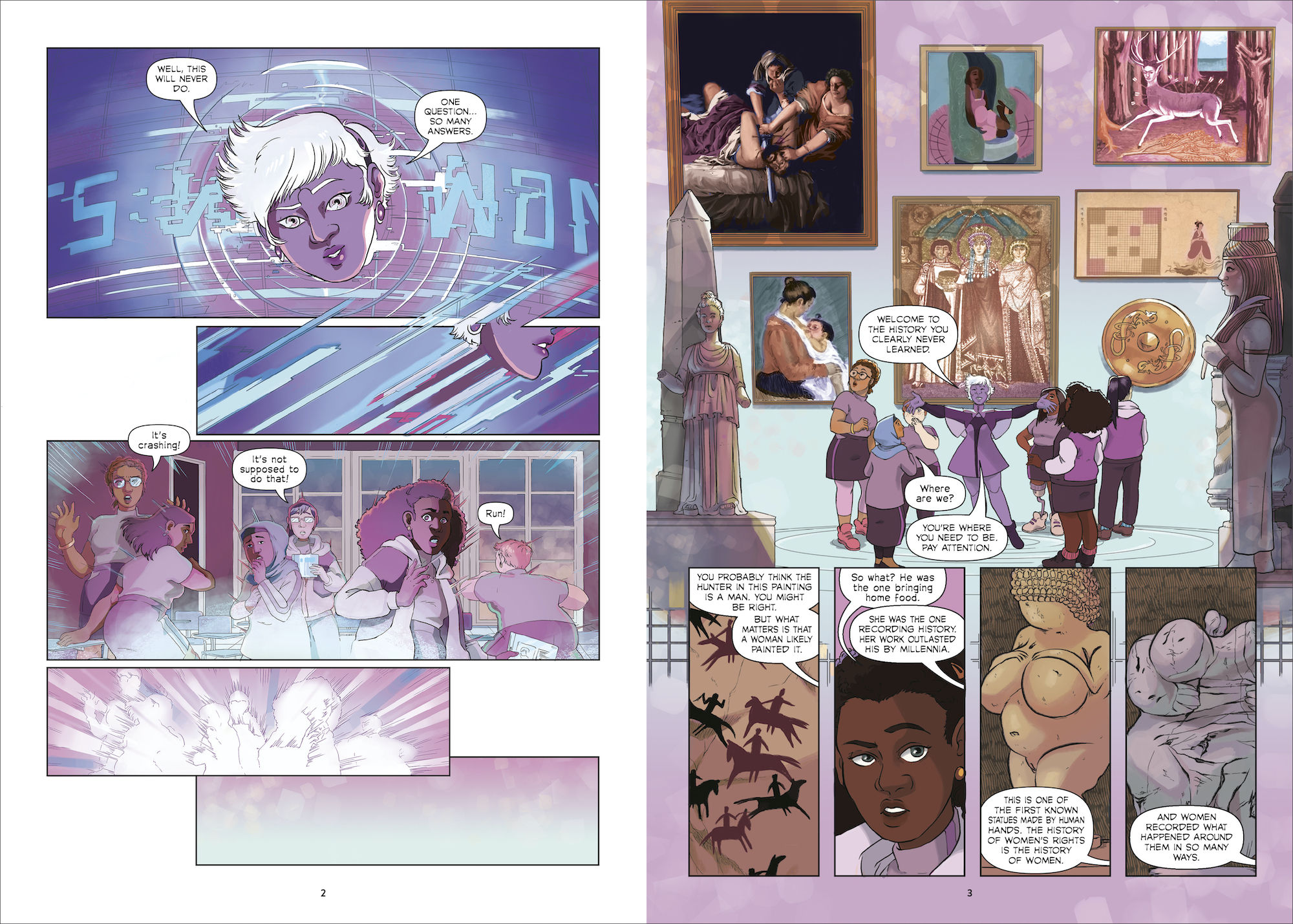

D’Amico: I thought it was helpful and important to incorporate art history into this, because I feel like art helps people with sort of a clearer image of what time period things were taking place. If you think back to ancient Greece, most people have a fairly clear image of what ancient Greek art looks like, but they might not know specific historical figures or locations. So that was something that I thought was important to include. I was also very excited, and she agreed with me on that.

Kendall: The real defining factors were a sort of rubric in my head. Because it was visual, I needed to have some way to visually represent them. They needed to be important figures in that time frame when it came to women’s rights in some way, shape, or form, whether for good or for ill. I needed to be able to connect them to things that were happening around them. So it was never a, “So and so climbed a mountain and it had no impact on anyone else.” That’s a cool historical figure, but it doesn’t really help the cause of women’s rights. That was my own internal metric for figuring it out. And we end with that as my guideline. There’s a whole bunch of people I couldn’t include because there were only so many pages.

The Beat: That answers another question I had for the criteria in making the cut, because I noticed there were some notable people like Margaret Thatcher. She’s not the most ideal choice, but she was the UK’s first woman Prime Minister, and I didn’t see her in the book. I was wondering how she got cut?

Kendall: Despite that Margaret Thatcher quote, I actually couldn’t find anything Margaret Thatcher had really done to advance the cause of women’s rights. I tried because I thought that Thatcher and a couple of others would be important to show, but Margaret Thatcher will probably go down in history much later as something of an aberration. Like, she’s one of the worst, and I already put in Queen Elizabeth, who didn’t do that much for women’s rights, but Queen Elizabeth technically did more for women’s rights than Margaret Thatcher.

The Beat: What was the editorial navigation like? Were there any women that you had to fight to get in or keep out?

Kendall: You know, the closest we came was a conversation. My editor Caitlin, she was like, “Well, I don’t want it to feel like a yearbook.” I said something along the lines of, “It won’t when I’m done, because I think somewhere in the middle of the process, it was kind of like this with a lot of people. How are you going to all of these people on a page and have the narrative keep going?” And then we figured that part out.

The closest I think in terms of pushback was a couple of, you know, “This person is sort of controversial.” And I was like, “Yeah, I know.” I’ll give her credit, Caitlin really was just asking questions, like she wasn’t trying particularly to push hard. She was just like, “Is this where you want to go? Oh, it is? OK. We’re going to talk about the good and the bad.” That was one of the things — like, we got to the chapter where I talked about the impact of queens on the world and I do realize that some people reading the book were like, it’s like you made them culpable for slavery and terrorism, as they were.

The Beat: Understanding that in the age we live in, you can get an answer for most things in seconds, but I’m sure there was more involved. Can you take us through a little bit of your research process?

Kendall: I’m going to tell you I did use Wikipedia, because Wikipedia has a wonderful source list at the bottom [of its entries]. So that was a great place to figure out what women were doing in labor history, [for example]. Wikipedia certainly lacks pages for a lot of women, but it was a good place to find a name to then go actually research at the library or in books, things like that. Because even when something like a wiki doesn’t have a lot of information, one of the things you can often find is a name that will then lead you into someone’s webpage about that person, to their book about that person, to the Library of Congress archives. You know, one of the great things about historical research training is that it teaches you that nothing is ever really hidden. You just got to know where to start looking.

The Beat: Who were some of the more influential or interesting women that you wish you had more space to give?

Kendall: Oh man, all of them. But no, I would say that one of the really influential things is that you’ve got Queen Irene, you have a lot of Black suffragettes, a lot of labor history and disability history, where even if I couldn’t put every single person in, I just really wanted to make sure that we talked about the fact that the women in the ADA (American Disabilities Act) for instance — their work has a wide-ranging impact. It’s not like they just won it for three people. That’s something that’s going to impact and has impacted generations. It made work more accessible, made school more accessible, allows for people to be able to be part of the world.

When I’m talking about trans liberation, for instance, I know there are some people who are feeling a kind of way, but opening the door for those folks to be seen, to be part of communities, to build communities, to have access to health care. Lesbians who were taking care of gay men when the AIDS crisis first breaks out, that history sort of gets buried. But without them, the losses would have been greater. They literally saved lives and literally helped make it possible for us to know what happened, because our government wasn’t doing anything to keep track of it or to help. A lot of folks would have ended up really just lost to history in the potter’s field somewhere if it weren’t for the fact that women have always kept the records, have always shown up in a crisis. The history of the world is the history of women.

The Beat: What was the thought behind using artificial intelligence and students as our storytellers? I was more than halfway through the book before I noticed one of the students had a prosthetic. What were the discussions like when designing them and the general technique behind crafting the art for the book?

I just sort of started designing a very wide variety of characters and then together we sort of narrowed it down to these six students. And then the A.I. teacher, she just came out of like a series of trying to design a character that looks futuristic and very feminine looking but also feels very approachable and not the typical image that you see in media of a feminine artificial intelligence-looking character. Generally how I work is, I like to sketch on paper, pen on paper, but then when I’m going in to work on a finished illustration, I ink digitally. I’ve made a lot of my custom pens and stuff so it doesn’t have quite that, you know, usual digital feel.

Amazons, Abolitionists, and Activists is available wherever books are sold. Mikki Kendall’s next book, Hood Feminism, hits shelves Feb. 25, 2020. To keep up with Kendall and D’Amico on Twitter, follow them at @karnythia and @adamicoarts, respectively.