In 2006’s Lucille, French cartoonist Ludovic Debeurme gave a surreal and somber tone to a doomed love story, following the individual wrecked lives of anorexic Lucille and the emotionally troubled Arthur, and how they come together as a means of escape.

Renee, his 2010 follow-up to that work, is a less of a linear book and allows the surreal sections to take up more room. Split up into several stories, we do catch-up with both Lucille and Arthur, but there are additional lives being followed here, though their exact connection is not immediately revealed.

Arthur is now in jail, turning more inside himself as he tries to block out the attempts of other prisoners to make contact with him. That all changes when he is able to focus his personal rage on his new cellmate, who the other prisoners claim is a convicted child molester.

Lucille visits Arthur, but has returned to her mother and is very much now a shell of the person who was beginning to blossom by the end of the previous book. She is flirting with starving herself again and giving into depression, her love with Arthur proving a very slender thread to hang onto when placed against the reality of her situation.

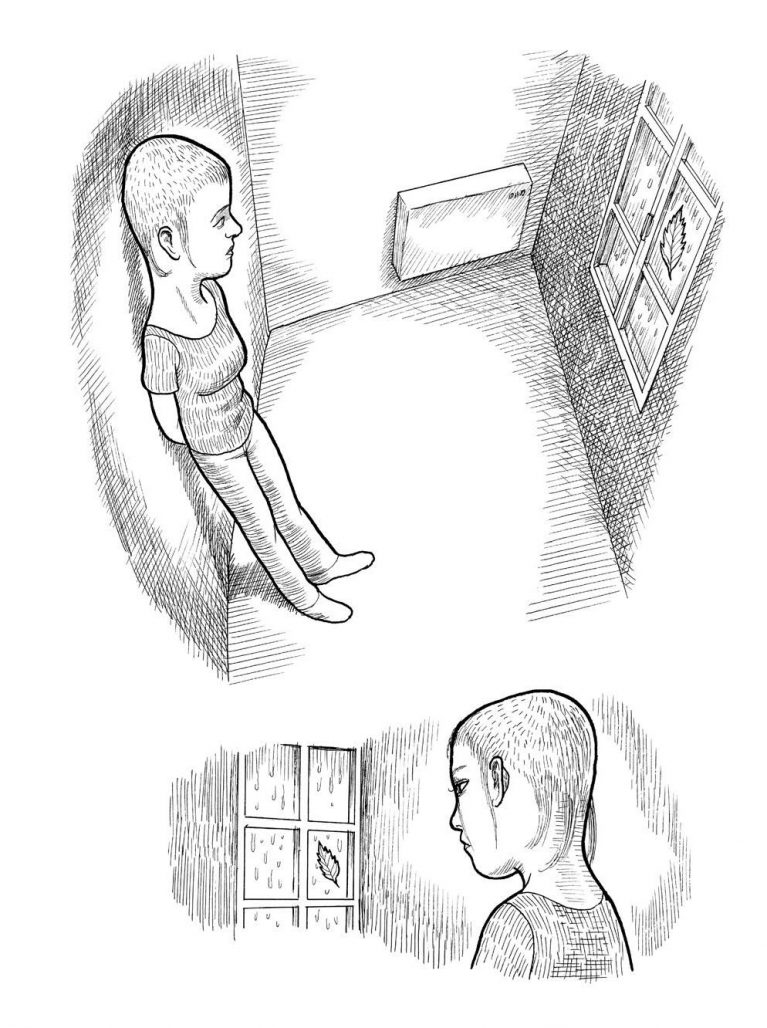

As the individual dramas sprawl to include the personal stories of others, and then pull back to Lucille and Renee, the emotional landscape become clearer and Renee’s story reveals itself as one steered by what isn’t there, absence through loss. The fantastic sections of the book — featuring, among other things, a creeping impish creature, flying insect versions of characters, and humans transforming into misshaped grotesqueries — become visual totems for both the things that are absent and the fears that are entirely present.

But most prevalent in the drama are the things men do, and the effect it has on women. Whether they are trying to protect or hurt or escape, the effect on the women is always the same, being charged with the stewardship of a huge empty burden that’s wrapped in pain. That’s what both Lucille and Renee are left with, and absolution from the responsibility can only come through their own personal actions.

It’s a gloomy work, to be sure, and the way Debeurme lets the story unfold so cryptically just makes it more so. Populated with panel-less pages and crisp line work that’s improved on the previous book, this might actually be more than some readers can bear. It won’t move you to to tears, it’ll probably just heighten a familiar darkness around your head that won’t be able to easily shake.