A must read and a must-read for masochists top our linkage today, both returning to topics that were much on the minds of anyone in comics about 30 years ago — oldies but goodies.

First and most importantly, library professor Carol Tilley has been going through Dr. Fredric Wertham’s notes and found out that he was, to use a technical term, full of hooey.

Wertham’s personal archives, however, show that the doctor revised children’s ages, distorted their quotes, omitted other causal factors and in general “played fast and loose with the data he gathered on comics,” according to an article by Carol Tilley, published in a recent issue of Information and Culture: A Journal of History. “Lots of people have suspected for years that Wertham fudged his so-called clinical evidence in arguing against comics, but there’s been no proof,” Tilley said. “My research is the first definitive indication that he misrepresented and altered children’s own words about comics.”

In case you are a newcomer, Wertham is the 50’s era psychologist whose book Seduction of the Innocent posited that crime comics were driving the huge surge in juvenile delinquency in the US, and his research drove the Kefauver hearings which pretty much decimated the American comic book industry for a decade, and ushered in the Comics Code.

Wertham remained the primary villain for the comics industry up until about 10 years ago—a Joker-like figure who could emerge at any time and get comics thrown back in the clink of highly censored pablum. Fears of “A new Wertham” were a motivating force for at least one comic book publisher for most of his career. But in the last decade, the proliferation of manga—with topics that would have made Estes Kefauver curl into a ball and cry “Oh mother, please help me!”—without significant blowback seems to have put the fear of a single crusader killing the medium to rest for a while. Which isn’t to say the CBLDF mustn’t remain vigilant, just that a Wertham style witch-hunt is unlikely.

So, finding out that Wertham’s influential research wasn’t all that well conducted—not exactly a shock, since comic books DIDN’T cause juvenile delinquency—is a nice little middle finger flip for comics to Wertham in his grave.

Tilley’s article also cites the case of Dorothy, a 13-year-old whose chronic truancy Wertham ascribed to her admiration for the comic book heroine Sheena and “crime comics,” omitting any mention of other factors listed in her case notes, such as her low intelligence, her reading disability, her gang membership, her sexual activity and her status as a runaway. Wertham also didn’t reveal that he never personally met or observed Dorothy; she was the patient of his associate, Dr. Hilde Mosse.

What makes this story such a must-read isn’t just the Wertham stuff, though. Tilley has written a paper called “Comics: A Once-Missed Opportunity”—however the working title when she delivered it at the ALA was “How Libraries Screwed Up.” She’s also unearthed a lot of VERY interesting research which shows that the comics medium pre-Wertham was actually achieving many of the multimedia educational purposes it’s now being lauded for:

“For a couple of years, 1950 and ’51, the state of Louisiana put out its annual report as a comic book,” Tilley said. “People recognized that comics were powerful. It wasn’t just kids reading them; grown-ups were reading them too. There was something to be said for that combination of text and image that could be a powerful communication tool.”

It’s this kind of “empowering” news for comics that was long lost for the era that though everything began with AMAZING FANTASY #15. I look forward to reading Tilley’s paper when it is published.

Now, onto another battle of the past. A few days ago I referenced Eddie Campbell’s essay “The Literaries”, a defense of EC comics on the basis of a picture being worth a 1000 words. A riposte to this has been delivered by critic Ng Suat Tong at the Hooded Utilitarian in a timid piece called The Comics Journal and Eddie Campbell: In Defense of Shit and Poor Logic.

Now before I go any further I must note that Ng is one of a trinity of critics who used to be found most frequently at the old Comics Journal message board who didn’t like anything. The other two are Domingos Isabelinho and Matthias Wivel. I wish I could link to some of the flame wars but a) it would be boring and b) my memory is just not that good. Suffice to say that an innocent comment about how you liked “The Death of Speedy” might be met by stinging repudiation on its banality and Jaime’s decorative facility masking cliche and so on and page after page of what Tom Spurgeon calls Nerd Court.

I’ve met Wivel and he’s actually a nice fellow (and the least terrifying of the trio); Ng and Isabelinho make early Comics Journal critics look like kittens with soft fluffy yarn balls. They definitely like some very interesting stuff, though and every medium needs demanding critics who ask questions and push back against established wisdom.

Anyway, since it was Ng’s original reappraisal of the EC oeuvre that kicked off the current reappraisal of the reappraisal, it’s only fitting that he take on Campbell:

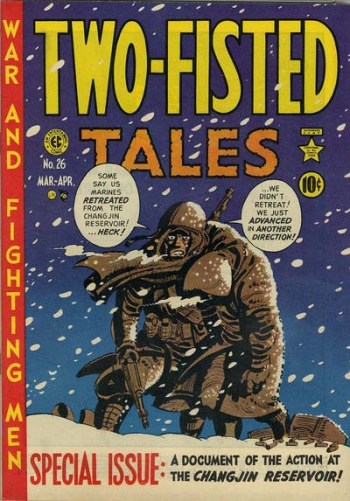

Once upon a time, there was a bastion of comics criticism which, it has been opined, stood against the hordes of barbarians trumpeting the works of John Byrne, Todd McFarlane and assorted other idolaters of caped beings. But time withers all, and like Saint Gregory of Rome, the rulers of that holy organ negotiated a separate peace with the hordes—the “empire” surviving but now a rotten shambles and a mockery of what it once stood for. It has been said that the purported ideals of that magazine never existed in the first place. That past is debatable, the present less so. What was once a hotbed of disagreement and debate has now become one of affirmation and boot licking acceptance. The rallying cry heard last week was a sermon to the converted, an affirmation of the god-like status of various revered cartoonists— that their comics remain untarnished by dint of an indefinable comic-ness Like many rallying cries, Campbell’s piece is long on rhetoric but short on substance. His primary example as to the brilliance of the EC War line is the cover to Two-Fisted Tales #27.

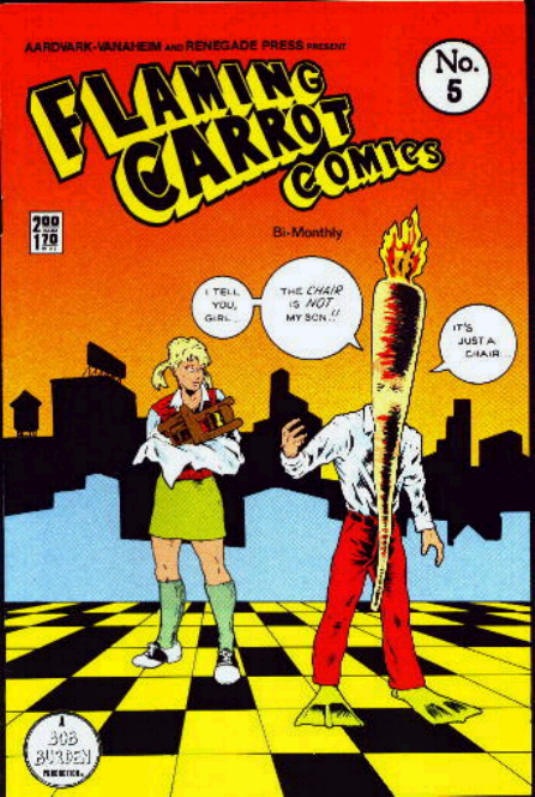

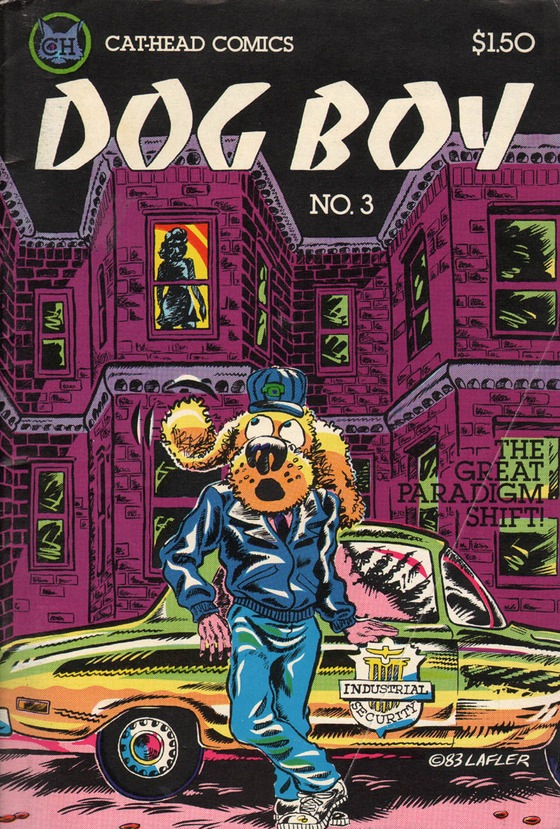

And it’s off from there. As usual, the comments quickly devolve although Campbell shows up at the end with a new defense, but the goat carcass being batted around by this particular buzkashi game is the old question of “ARE COMICS LITERATURE? ARE THEY ART?” which, once again, we settled that in the 80s, people, when Bob Burden published FLAMING CARROT #5 and Steve Lafler put out DOG BOY #3. This time WWI poetry, Birth of a Nation, the lyrics of the Rolling Stones , Bo Diddley and God knows what else are dragged around in order to prove that…people know things other than comics.

The Hooded Utilitarian is the most annoying comics website on the net because it has some of the best, smartest writers about comics, but they don’t seem to be interested in putting further arguments…instead they just like to argue in the comments. (I wish I had a nickel for every time the insult “Straw man!” is thrown around.) Isabelinho shows up with his own aphorism:

The problem is that a work of art is a work of art is a work of art (and I’m including literature here). Comics exceptionalism makes no sense.

Except that I don’t think anyone is saying comics are exceptional. Comics are Comics. Opera is opera. Etchings are etchings. Is Fun Home better than Boris Godunov? Is Jack Kirby better than The Cremaster Cycle? Can’t we just have a world FULL of things that are in some way amazing, beautiful, touching and mind boggling, and not just five or six Sistine Chapels?

I’m not even a big Kurtzman fan, but I get esthetic pleasure from looking at the cover to Two-Fisted Tales #27. It is about the same amount of pleasure that I get from listening to a song by Adele. It is not as great as the pleasure I get from listening to a song by James Brown, though, but looking at the page of Jack Kirby that Campbell alluded to, that is probably better than everything by Brown but maybe not Funky President or Sex Machine.

All of which proves beyond a shadow of a doubt that I can also reference things that aren’t comics! I win, internet! Suck it!

Questioning whether something is actually art isn’t so useless if one can define the standards he’s judging it by, and use those same standards to explain his reaction to the art in some detail.

There are problems when someone describes something as art simply because it elicits a reaction, but the would-be judge can’t explain either the standards being used or the reaction.

Banality in art is a problem when what’s being expressed has been expressed, by others or by the artist himself, many, many times and is so easy to do that there’s no longer any point in doing it. Being original doesn’t automatically make something good, but if someone is setting out to create art, being original means he’s sufficiently familiar with the field he’s working in to avoid repeating what others have done.

SRS

Hooded Utilitarian just seems to be a bunch of pseuds seeing who can be the biggest pseud.

“Nerd Court” is definitely going into my lexicon. Thanks, Tom/Heidi!

Doesn’t the use of the neologism “pseud” kind of brand one as a pseud?

Or do you have to use a word such as “neologism” too? ;)

Fair point though I don’t think it always holds true – however pseud has been in use since it was coined in the UK nearly fifty years ago so it’s not a very ‘neo’ neologism.

Perhaps snobbery is a better way of describing part of what’s at stake here, not least since it focuses on the activity rather than the person engaging in it.

“Bootlicking acceptance”, as Ng Suat Tong puts it, can just as easily apply to the act of licking ones own boots.

A) F*** you Frederic Wertham…

B) I Gave up on the Hooded Utilitarian long ago, the last post I enjoyed from them was one on Yoshihiro Tatsumi’s body of work, also by Ng.

I still haven’t finished Eddie Campbell’s article, but so far I get the sense that he isn’t critically praising / defending EC as much as using the argument as a launchpad for his view that comics been be appreciated as a unified visual narrative thing, and “bad” writing can’t, by that definition, sink the entire ship by itself.

It reminds me of the Nerd Court arguments over Brian De Palma movies: on one side are the people who think film should adhere to traditional literary standards and on the other side are the people who say, “It’s a MOVIE man, just LOOK at it with the sound off and you’ll be fine!” Then the fighting ensues. So that’s the argument Campbell was wading into, not the “We should all appreciate bad commercial art once it’s more than 40 years old” argument.

The best metaphor I can come up with for this argument is two third-world nations at war: Each invests what little defense funding they have in several fancy new fighter aircraft. The fighters are manned, they take to the skies, and duke it out in intricate, technology-driven aerial combat. Eventually, a victor emerges…or not…and no one on the ground gives a shit about any of it.

Every superhero fan should be grateful for Fredric Wertham. Without his crusade and the resultant Code, there would probably have been no superhero revival in the late ’50s and early ’60s.

With the imposition of the Code, horror and crime comics were killed, and the remaining genres (war, western, romance) were greatly watered down. Yet comics still had to tell visually exciting stories. Solution: bring back the superhero. Superhero comics allowed for visual spectacle, and for action without graphic violence. And, being fantasies, superhero comics were less upsetting to parents and other authorities than, say, a comic where the protagonist was an axe murderer.

Hi Heidi!

I may inadvertently have come across as a blowhard on the old TCJ messboard, but it was never one of my haunts. I think my total posts in the many years it existed must have clocked in under 25.

And I like many things! Including EC! What have I done to be lumped in with Domingos and Suat? I’m very fond of them both, but I also disagree with a lot of what they say and write, and I don’t think I’ve ever promoted the elitist doctrine they represent so well, have I? Please let me know. I’m confused.

Basically, I think this TCJ/HU/EC discussion sadly went off the rails just as it was getting interesting. Eddie’s piece was excellent food for thought. Although it was vague around the edges and can justly be criticized for it, I think he managed to say things clearly and concisely that I’ve been trying to say much less clearly and concisely for the last few years in my many arguments with Noah B and Domingos at HU.

Synsidar said:

“Questioning whether something is actually art isn’t so useless if one can define the standards he’s judging it by, and use those same standards to explain his reaction to the art in some detail.

There are problems when someone describes something as art simply because it elicits a reaction, but the would-be judge can’t explain either the standards being used or the reaction. ”

Finally, something Synsidar and I can agree on! Yes, it’s one thing to be an elitist critic, another to be an elitist whose only criterion is that he personally was impressed with a given work.

I would echo Heidi’s criticism to the extent that the HU critics usually don’t seem interested in breaking down stories to see why they do or don’t work, and sometimes seem alienated from the very idea that telling a story effectively can be a positive accomplishment. Tong’s essay is very much in this vein; if Kurtzman doesn’t write of war the way Tong thinks that the subject should be addressed, then Kurtzman is Bad Art.

George,

I think you’re essentially right that the superhero genre was the accidental beneficiary of Wertham’s campaign, although that was certainly not due to Wertham’s actual rhetoric, which condemned all forms of violent entertainment, and lumped the superhero genre in with the genre of “crime comics.”

Even if Wertham had no more effect on the industry than his sometime colleague Gershon Legman, I think it would still be proper to condemn both of them for having evinced the intent toward censorship. Morever, if Tilley is correct then he also falsified evidence, which is equally contempt-worthy. Up till now, the worst one could say was that probably a lot of the delinquents in W’s care caught on fast to what the Old Guy wanted to hear, and fed him stories about how they wanted to be sex maniacs and whatnot. But playing around with his supposed empircal data is far worse than that.

Arguably there were good developments that evolved from the presence of the Code. But just as with the Motion Picture Code, that doesn’t make either one good in and of itself.

One last thought: the reason that the argument about comics-as-art has lasted this long (I’d put it even further back myself) is because no one has successfully come up with a Theory of Art that applies equally to comics and other literature. All we have are a lot of little theories on comics specifically, which leads to a whole lot o’ nothin’.

Of course theories abound in academia, and it doesn’t stop the arguments there either. But at least the proponents have some semi-coherent ideas about the topics under discussion.

A problem with a comic book’s artwork, and a story’s use of a continuing character is that they both encourage manipulation of the reader. Artwork can elicit involuntary (programmed) responses; manipulating a reader who’s attached to a character is trivial. If someone reads a piece of fiction that uses a formula he’s familiar with, he’s letting himself be manipulated. Manipulation isn’t art.

One benefit of valuing originality in storytelling is that the original material, something a reader hasn’t seen before, forces him to react intellectually to it. Experienced readers love being surprised by a successful story.

SRS

I’m not a Wertham fan. His work was slanted and sensationalized. And he didn’t bother with footnotes or endnotes listing his sources (i.e., which comics he took his examples from), which wouldn’t fly in any “scholarly” work today. In fact, he took some criticism for it in 1954.

Of course, “Seduction of the Innocent” wasn’t aimed at academics. It was aimed at a large mainstream audience … and at parents who wanted to be told they bore no responsibility for how their kids turned out. I think it was Robert Warshow who described “Seduction” as sort of a crime comic book for adults.

However, many people today may not realize how transgressive EC (and “Crime Does Not Pay” and other comics) were in their time. EC went beyond what was permissible in movies, radio or TV in the early ’50s. This was a time when self-censorship was the rule. In this climate, they were almost asking to be attacked.

http://www.commentarymagazine.com/article/the-study-of-man-paul-the-horror-comics-and-dr-wertham/

Here is Robert Warshow’s great essay, “Paul, the Horror Comics and Dr. Wertham” (June 1954). It’s fascinating as a reaction to the controversy as it was happening. Warshow stakes out an intelligent middle ground — he wishes his son was not an “EC Fan-Addict,” but still disapproves of Wertham’s tactics. Warshow thought “Mad” was very funny, but not appropriate for children.

“A problem with a comic book’s artwork, and a story’s use of a continuing character is that they both encourage manipulation of the reader. Artwork can elicit involuntary (programmed) responses; manipulating a reader who’s attached to a character is trivial. If someone reads a piece of fiction that uses a formula he’s familiar with, he’s letting himself be manipulated. Manipulation isn’t art.”

Actually, I think the element of manipulation in art is very strong, it’s just not as obvious. Some critics make much of ambiguity. But does Nabokov really just leave it up to the reader as to whether or not Humbert Humbert’s take on morality is genuinely moral? I would say that Nabokov has definite ideas on the subject, and that he manipulates readers into taking his view of things– even if he makes his points more subtly than a Jerry Siegel.

I don’t know why it would make any difference as to whether or not one is dealing with continuing characters. When I considered buttressing my above argument that some HU guys don’t like traditional stories, I returned to the Ng Suat Tong essay whose reprinting started the fracas:

“Once we recognize this, we must begin to wonder why some of the most esteemed critics in the field so often choose to place these comics over any other series of adult war comics. Do we find Joe Sacco’s truthful and engaging writings concerning Palestine and Yugoslavia hampered by his lack of exciting narrative technique and close-ups? Do our healthy appetites for dramatic, swanky portrayals of death betray our immature desires? This is the corrupting influence of the EC War line: artfulness and dexterity in place of truth; voyeurism without horror; content in the service of style instead of the reverse.”

To me this is just as much a “cri de couer” as your own against the evil power of manipulation. But all of the EC stories Tong is condemning are anthology stories with non-continuing characters. Ipso facto, the presence of continuing characters makes no essential difference to the presence or absence of manipulative elements.

Yeah, Warshow was a cool dude. He was pretty important in the development of film genre studies as well.

Yes, Warshow’s essays on westerns and gangster movies are classics. They’ve influenced writers for 60 years. I’d recommend his book, “The Immediate Experience,” for anyone who wants to experience pop-culture writing at its best.

Comments are closed.