The Beat’s Gregory Paul Silber has been accused of having a bit of an… obsessive personality. Each week in Silber Linings, he takes a humorous look at the weirdest, funniest, and most obscure bits of comics and pop culture that he can’t get out of his head.

On Friday, June 23rd at 10am PST, I’m going to be moderating my first panel, let alone my first panel for Comic Con International. Well, technically it already happened in late May, but next week (as of the publication of this article) is when you can finally stream it, being that CCI is doing another year of “Comic Con @ Home” rather than holding it in San Diego as they did every year before the world succumbed to its apparent death spiral. Cosmic anxiety aside, I’m sincerely proud of how the panel turned out, and I hope you’ll all tune in. It’s called “Ducks All the Way Down: Metafiction in Comics.” Add it to your Google Calendar here.

I promise the title will make sense once you watch. I also promise it’s going to be a great watch, because it was seamlessly edited by The Beat’s Sajida Ayyup, and features a killer guest list: writer/producer Marc Guggenheim (DC’s Legends of Tomorrow); letterer, Youtuber, and editor Hassan Otsmane-Elhaou (PanelXPanel); writer Ann Nocenti (The Seeds); and The Beat’s own features editor Avery Kaplan, the last of whom played a massive role in helping put this panel together in the first place. Oh, and there’s a special cameo I won’t spoil here.

I’ll let you experience all that for yourself when the stream goes live. Besides, I let the panelists do most of the talking. For now, while you’ve got me here alone, I’d like to dive deep into the subject of the panel, metafiction: what it is, what it isn’t, and why it’s so endlessly fascinating.

Feel free to refer to the dictionary for definitions of metafiction, but the shorthand I always use is “fiction about fiction.” It’s self-referential, self-reflexive fiction that comments on the nature of fiction itself, both in terms of consumption and creation. If you’re familiar with the term “breaking the fourth wall,” that’s basically what we’re talking about here. Whereas most fiction, by default, thrives on the suspension of disbelief so that audiences can immerse themselves in a fictional world, metafictional texts go out of their way to remind audiences of their inherent artifice.

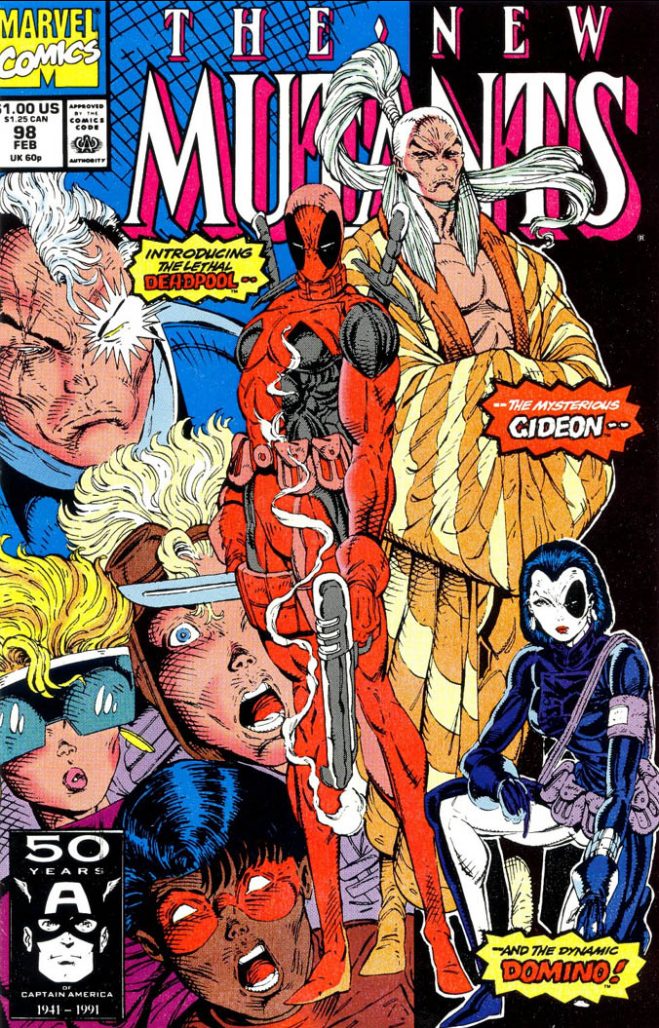

Among comic book fans and readers of The Beat, the go-to example of metafiction may be Deadpool. While it took some time for this aspect of his characterization to develop following his first appearances by creators Fabian Nicieza and Rob Liefeld, Deadpool became one of comics’ most iconic smartasses when he gained the distinction of knowing he’s a comic book character. That’s why he’s famous for making snarky comments to the reader about the ridiculousness of his own misadventures, and why the Deadpool films starring Ryan Reynolds can stand out among the crowded superhero movie market.

The thing is, while Deadpool is certainly a meta character, and some of his stories can be metafictional, he’s not exactly who I think of when I talk about metafiction. Most of the time, Deadpool’s meta moments amount to little more than quick gags. That’s not a value judgement. I like jokes! Jokes don’t necessarily have to have grander ambitions than funny hahas! But just because Deadpool makes a funny joke about being in a comic, doesn’t mean the story in which that joke appears makes a larger point about the nuances of fiction. Which is fine! But it’s not necessarily metafiction.

(Editor’s Note: I would like to also add that what became Deadpool’s meta-schtick is almost entirely cribbed from Keith Giffen‘s Ambush Bug. The Beat as an organization will not stand for any form of Ambush Bug erasure. Back to you, Greg! –JG)

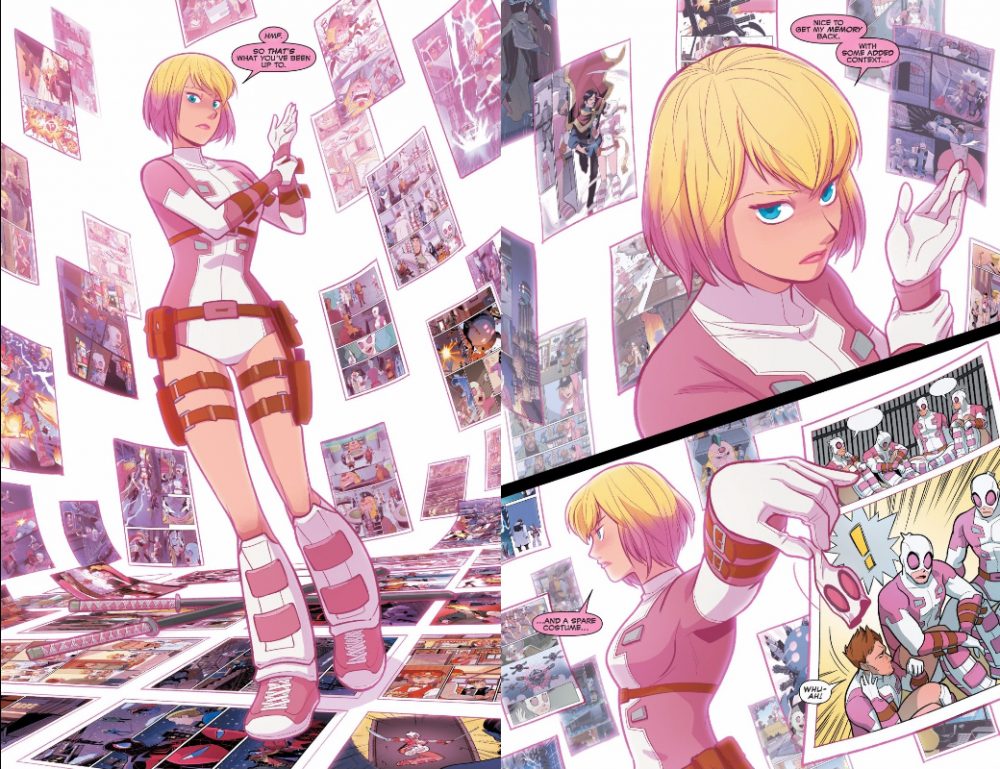

The Marvel antihero who best aligns with the idea of metafiction I’m talking about is Gwenpool. Contrary to what you might assume from her name and Chris Bachalo‘s costume design, she’s not a gender-swapped Deadpool merged with Spider-Man’s erstwhile girlfriend Gwen Stacy… even if that was pretty much the case in her first appearance, on a variant cover of 2015’s Deadpool’s Secret Secret Wars #2. Following these humble beginnings, writer Christopher Hastings and art team Gurihiru, with the help of editors Heather Antos (upon whom the character was partially inspired) and Jordan D. White, fleshed Gwenpool out into something far more interesting, resulting in The Unbelievable Gwenpool: one of the best superhero comics of the 2010s.

Gwenpool is so named because in her secret identity, she’s Gwendolyn Poole, an ordinary 18-year-old hailing not from the Marvel Universe, but from “our” world. But she’s a massive Marvel fan, so when she finds herself transported into the “616” Marvel Universe, her encyclopedic knowledge of Marvel Comics becomes her superpower. Not only does she have intimate knowledge of superheroes and supervillains that aren’t widely known among other characters in the Marvel Universe, like virtually every major superhero’s secret identity and origin story, her knowledge of comic book tropes helps her navigate a perilous world in which she’s constantly at risk of being killed by vampires, killer robots, or whatever other cataclysmic events Marvel heroes face off against in their monthly adventures.

That’s why she adopts a costumed alter-ego: ordinary, non-costumed people in superhero comics can amount to little more than cannon fodder for bad guys. But if she can stand out with an outlandish pink, pantsless outfit and a hilariously chaotic persona, she can’t die because readers would demand to follow her through more adventures.

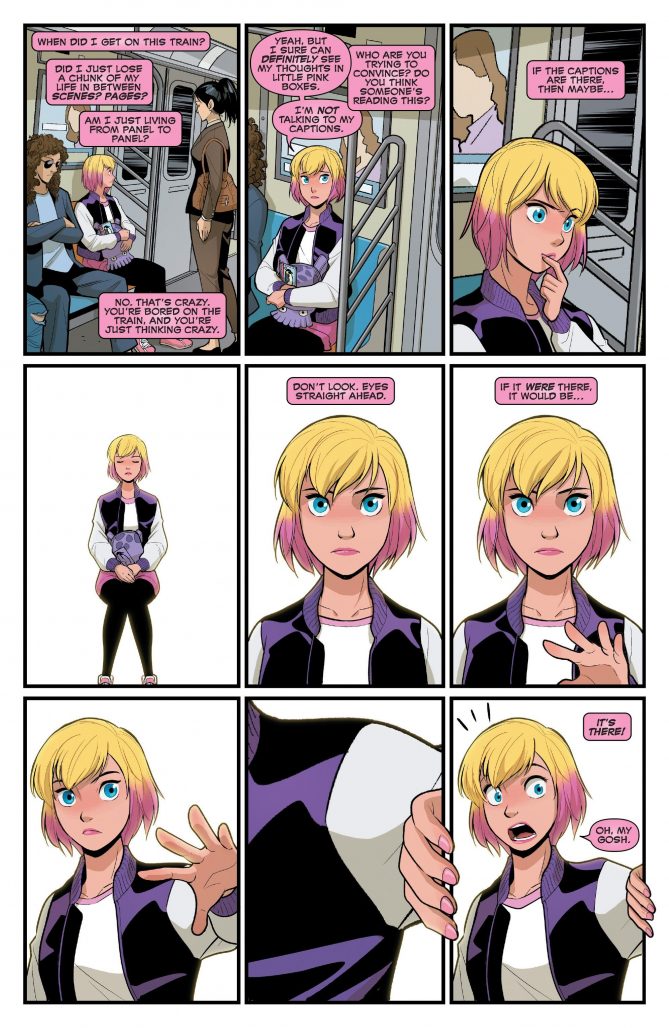

Running for 25 issues (plus a few specials and shorts) from 2016-2018, Gwenpool’s initial “solo” series is about as metafictional as it gets. It’s full of laughs and zany action, but every story beat serves to advance the metafictional themes. As the series progresses, Gwen’s powers become more nuanced to reflect her story’s growing complexity. She becomes so hyperaware of the comic book mechanics surrounding her that she starts to see word balloons and caption boxes as physical objects, to the point where in one memorable sequence, a flurry of word balloons fill her room until she’s pushed out the window. Soon, she develops the ability to move freely through panels. It’s brilliant stuff.

Metafiction can and should have something to say beyond the fictional framework it occupies. As the series starts winding down, we learn that there’s something much sadder beneath the surface of Gwenpool’s seemingly anarchic romps. Back in the real world, before she escaped to the Marvel universe, Marvel comics were her figurative escape. It’s something I could certainly relate to at various times in my life, and I know legions of other genre enthusiasts feel the same way: Gwen was unhappy with her place in the real world, and fiction – in this case, Marvel Comics – offered her much-needed refuge. But as Gwen soon learns, over-reliance on escapism has its own perils.

Sometimes when I’m writing this column – or any piece of criticism, really – I wonder how many readers think “man, this guy is really overthinking it.” I suppose that’s possible, but I became a critic, and a writer in general, because I can’t help but overthink the media I consume, especially the written word. It all goes back to how I became a writer in the first place. Let me explain:

I first decided I wanted to be a writer when I was about eight years old, sitting on the foot of the stairs after I finished reading Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets. A warm feeling washed over me, and I decided that whatever it was that I was feeling, I wanted to be able to give that to others.

(Obviously, it wasn’t until many years later that I’d learn Potter author J.K. Rowling is aggressively transphobic. I won’t pretend I didn’t love her work for as long as I did, or deny her massive influence on my career, but I can’t in good conscience support her work anymore, knowing she’s using her hugely influential platform to actively harm my trans friends.)

Like most writers, my love for writing is derived from a love of storytelling. But my passion as a writer is also the result of feeling forced to second guess myself anytime I communicate. I have a lisp, and for much of my life I also had a stutter, which I mostly managed to clear up even if it still occasionally comes out in moments of intense emotion. The lisp I never got rid of, though. Adults are generally more polite than children, so it’s not at the front of my mind as constantly as it was in childhood, but I do still sometimes get shitty comments about it. A conversation I’ve had more than once:

PERSON: Did you know you have a lisp?

ME: You know, you’re actually the first person to tell me that.

PERSON: Really?

ME: No.

As a kid, especially in middle school, it was brutal. I’ve written about that before. What I don’t think I’ve written about is how being bullied for my lisp made me desperate for a way to communicate in which I wouldn’t be interrupted or misunderstood. People could choose not to read what I write, but at least the information is there, and I could craft it meticulously until I’m as certain as I possibly could be that I’m getting my message out exactly as I intend, without someone stopping me midway through to tell me I’m doing it wrong, effectively ignoring everything I said up until that point and preventing me from getting to the next point I was trying to make.

Metafiction is fiction for people like me, and maybe you too: people who are intensely aware that every detail in a piece of art is a deliberate choice which the artist likely agonized over. I realize how pretentious this may sound, but I don’t think I’m capable anymore of enjoying fiction purely as escapism. Other writers and artists I’ve spoken to about this have expressed similar sentiments. We’re constantly asking ourselves “why did the artist make that choice? Why didn’t they make this other choice? What’s working? What isn’t? What can I learn from this artwork that I can apply to my own creations?” Sometimes I hear people describe a movie or comic or whatever as “turn-your-brain-off” entertainment, and I envy them. When I’m taking in a piece of media, there’s always a part of me that’s still working.

That might sound more tragic than it is, because the truth is that little brings me more joy as a reader than metafiction done right. That’s one of the reasons why Grant Morrison is one of my favorite writers, and why I bring them up so often in this column that’s largely about searching for joy in the media we consume. Morrison doesn’t shy away from deadly-serious themes like nuclear warfare and suicidal-ideation. But there’s a playfulness at the heart of their best work. Morrison is a writer obsessed with the concept of story itself, and clearly loves showing their readers how it all works.

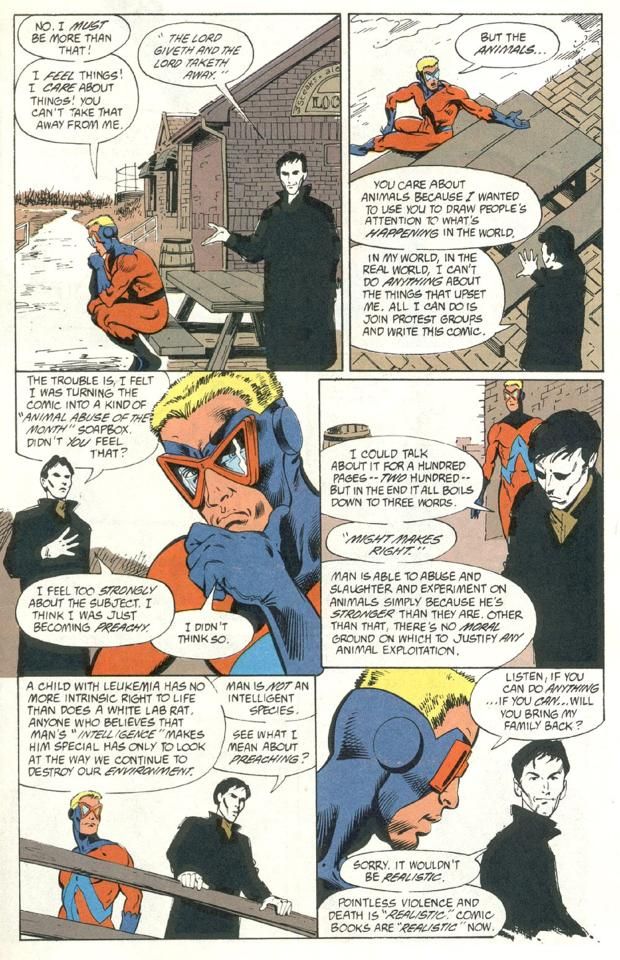

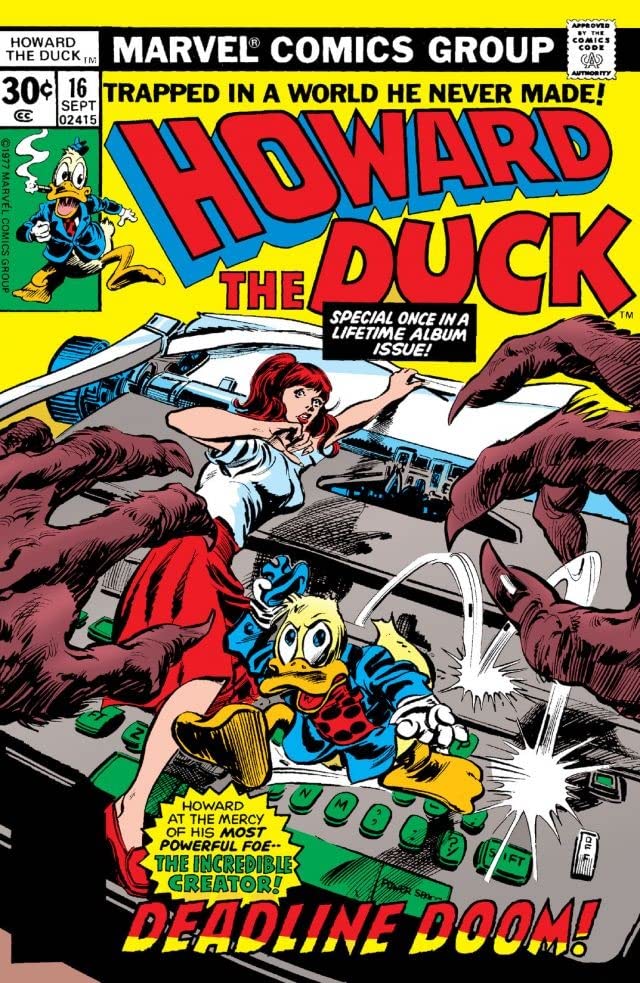

Which brings me to my favorite Grant Morrison comic, one of my favorite comics of all time, and the comic that crystalized my love of metafiction: Morrison’s Animal Man run with artist Chas Truog. Over the course of the series, increasingly strange and horrible things happen to Buddy Baker, the titular Animal Man. In the process, he slowly-but-surely starts to suspect that an unseen, omnipotent force is deliberately ruining his life. This malevolent spirit is of course his writer, Grant Morrison. The series culminates with Buddy coming face-to-face with Grant themself, who calmly explains over the course of the final issue why they, as a writer, had little choice but to torment Buddy through their writing, because fiction thrives largely on the suffering of fictional characters.

It’s dark, sure, but it probably sounds darker than it is. At least, that’s not how it was for me. When I finished reading it for the first time a decade ago, I spontaneously stood up and applauded. Nobody was there with me in my dorm room, not even my roommate, let alone Grant Morrison. But I was so overjoyed with the mastery by which this story laid all its cards on the table that I couldn’t resist the instinct to extol its glory.

Metafiction is exhilarating. It’s stories gaining sentience and directly acknowledging you, the reader. Metafiction is fiction for people who can’t stop thinking about fiction.