The Beat’s Gregory Paul Silber has been accused of having a bit of an… obsessive personality. Each week in Silber Linings, he takes a humorous look at the weirdest, funniest, and most obscure bits of comics and pop culture that he can’t get out of his head.

When I moved back home after college, I was heartbroken to realize I had no choice but to stop buying comics. I’d spent $20 on comics each Wednesday with the money from my campus gig as a writing tutor, but flat broke with the hope of landing an entry-level job seeming increasingly impossible, I had to stop reading incredible comics that were coming out at the time like Pretty Deadly and G. Willow Wilson and Adrian Alphona‘s Ms. Marvel. Luckily, some sympathetic family members bought me a Marvel Unlimited subscription for my birthday, and that’s how I discovered one of my favorite comics: the original run of Howard the Duck by Steve Gerber, Frank Brunner, Gene Colan, et al.

Here’s the thing about having a reading diet of like 90% Marvel Comics for a year: even if you love Marvel superheroes as much as I do, eventually, you get a little sick of them. Don’t get me wrong, I discovered some great comics during that time like Mark Waid and Mike Wieringo‘s Fantastic Four run and a whole lot of Jack Kirby goodness, but eventually, I got to a point where I was desperate to find something on the Marvel Unlimited app that wasn’t about punching (please don’t misunderstand: I love comics about punching).

Enter Howard the Duck, a comic that I vaguely remembered a high school buddy describing as “existential” and “really smart actually.” He wasn’t wrong. Make no mistake, Howard the Duck is a Marvel comic, right down to a Spider-Man appearance in the first issue of his eponymous series (Howard first appeared as a member of Man-Thing’s supporting cast in 1973’s Adventure into Fear #19 before the debut of his own title in 1976). But thematically and stylistically, it’s as far from what most mainstream comics were doing at the time as Earth is from Duckworld.

Let’s get this out of the way: chances are, if you’ve heard of Howard the Duck, it’s because of the infamous 1986 film starring Lea Thompson that’s widely considered one of the worst films ever made. I wouldn’t know. I never saw it, and since I love Gerber and company’s original comic too much to want to watch an adaptation by a producer/screenwriter who declared “It’s a film about a duck from outer space… It’s not supposed to be an existential experience” (yes it is!), I probably never will.*

(*Editor’s Note: Here we have Greg giving me assignment ideas unprompted. –JG)

Either way, if your only familiarity with Howard comes from a film where they gave ducks boobs for some reason, I urge you let go of that frame of reference for a comic that’s genuinely funny, brilliantly postmodern, and utterly transcendent.

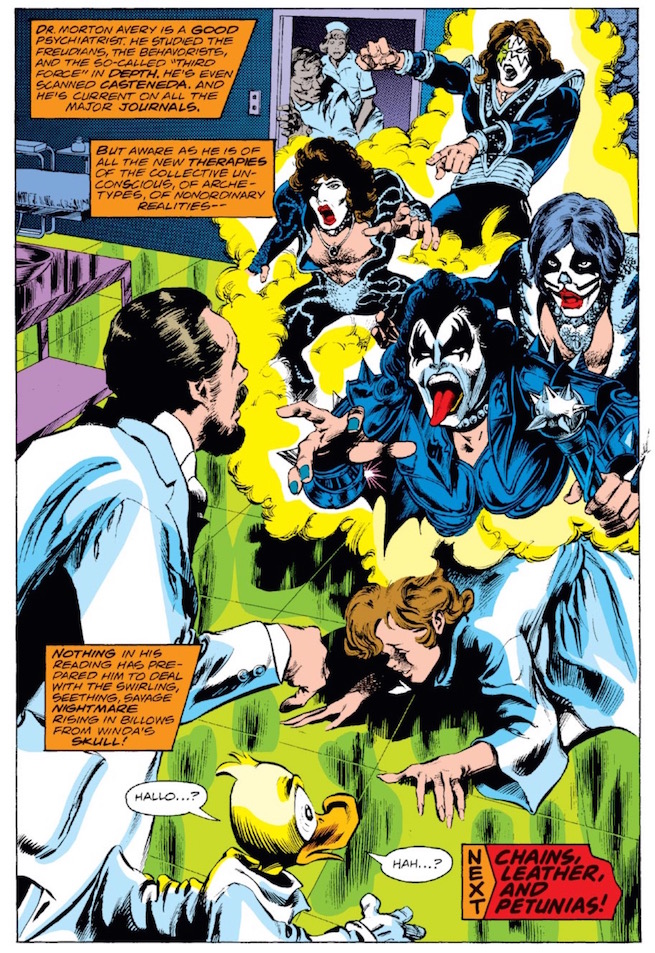

Of course, as sublime as they are, those 27 issues of Howard the Duck penned by Steve Gerber, the bulk of which were penciled by Gene Colan, may not be the kind of thing that pleases stuffy intellectuals, even if only because it’s a Marvel comic book called Howard the Duck. It’s too aggressively bizarre, and with Gerber removed from the series prematurely due to his habitual deadline delinquency, it doesn’t really have an ending. Reading it today, it’s clear that Gerber wasn’t writing for ’70s college professors, but their smart stoner students.

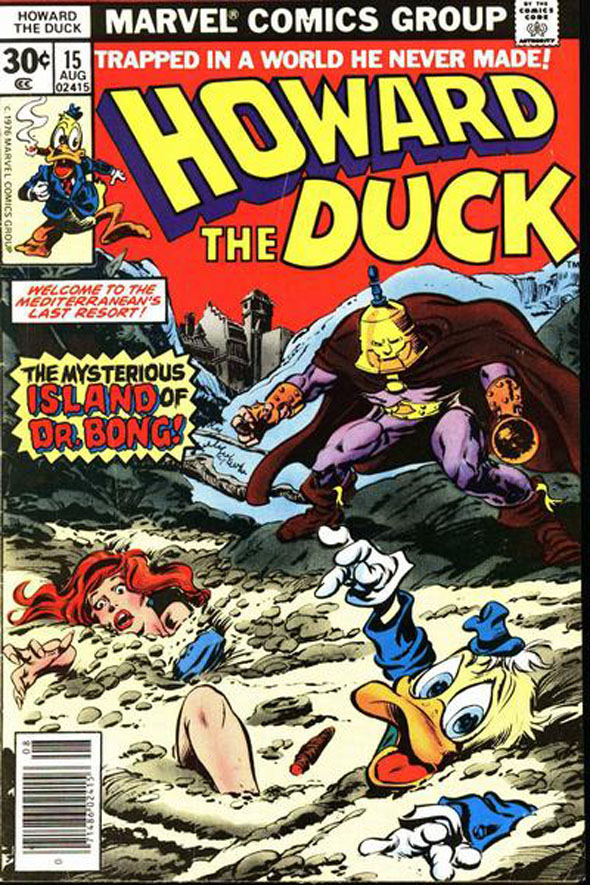

That’s not to say by any means that you need to be high to enjoy Howard (I read every issue sober), but come on. Howard fights a supervillain with a bell on his head named “Dr. Bong.” Gerber knew who was reading these things.

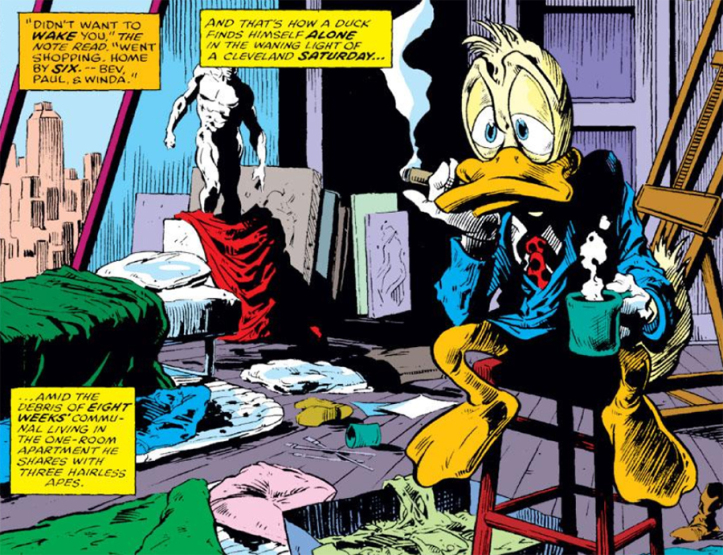

Like almost all Marvel comics of the era, Gerber’s Howard the Duck has a loose narrative thru-line from issue to issue while remaining highly episodic. The overall plot concerns the oddball misadventures of a fast-talking, cigar-chomping duck from outer space “trapped in a world he never made” on Earth. Basically, it’s a fish-out-of-water story, with Howard making pointed observations about 1970s America while struggling to be taken seriously. With the exception of his friend, unrequited love interest, and frequent traveling companion Beverly Switzler, most people can’t look past Howard’s inexplicable existence enough to listen to him, no matter how articulate or urgent his words are. “But… you’re a duck” may as well be the series’ catchphrase.

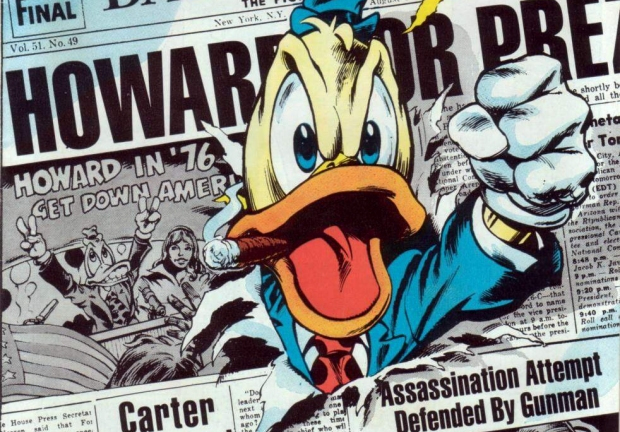

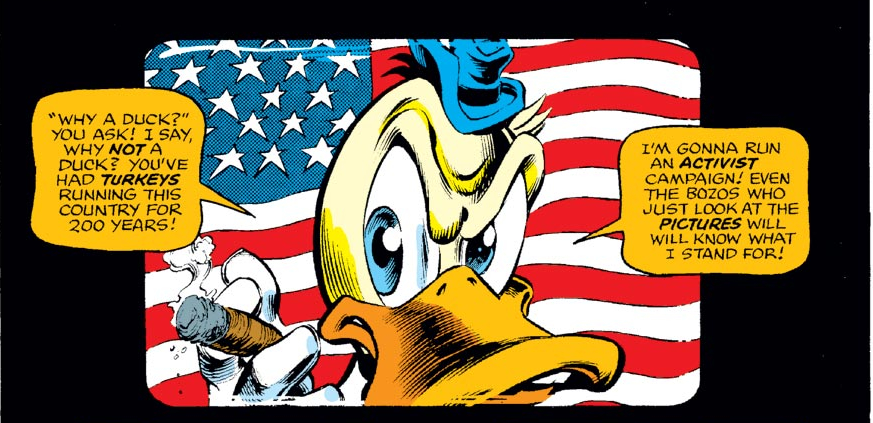

I don’t throw around the phrase “ahead of its time,” but Howard the Duck is one of the few pieces of media for which I feel it’s appropriate. Granted, Howard is “of its time” in several ways, including the gag of Howard running for President to coincide with the real-life 1976 POTUS race. The trends and social mores that Gerber, Colan, and the rest of the creative team critique and poke fun at are often distinctly ’70s. It’s not the targets of Gerber’s social commentary that makes Howard the Duck read like a comic of the future, but the fact that satire this sharp and daring was in a 1970s Marvel comic at all.

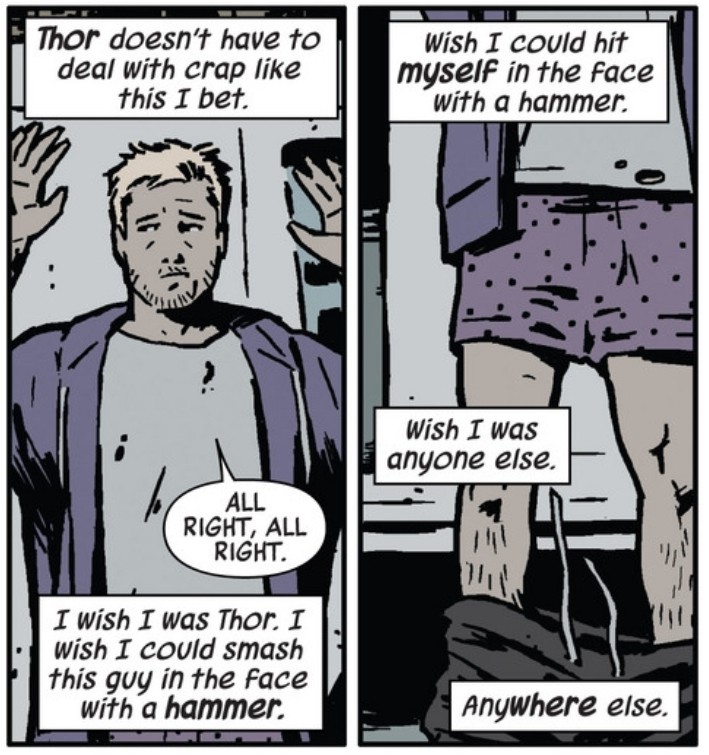

In a lot of ways, Howard the Duck reads like the kind of 2010s superhero comics I fell in love with as a college student and struggling post-grad, comics that largely eschew the trappings of traditional superheroics in favor of genre-benders that play with readers’ expectations of what mainstream comics are capable of.

Matt Fraction, David Aja, Annie Wu, et al‘s Hawkeye, a comic about the titular Avenger fighting slumlords and the ennui of vaguely-30-something single life in Brooklyn, shares some Howard the Duck DNA in the way that it presents feeling like an outsider (Clint Barton being a relatively ordinary man among super-powered gods; Howard being an alien bipedal talking duck among humans) as an existential crisis.

This may seem like a tenuous connection, but I see some Gerber influence in those existentially disconcerting superhero comics with which Tom King made a name for himself a few years after Hawkeye, too. They’re not nearly as trippy as Howard the Duck, and King generally favors different themes and styles from Gerber, but I’m not sure King and Gabriel Hernandez Walta‘s The Vision could exist without Howard the Duck proving that there’s no reason why Marvel comics can’t lean on heavy philosophical conversations between a duck and a nude model or a robot and his robo-wife.

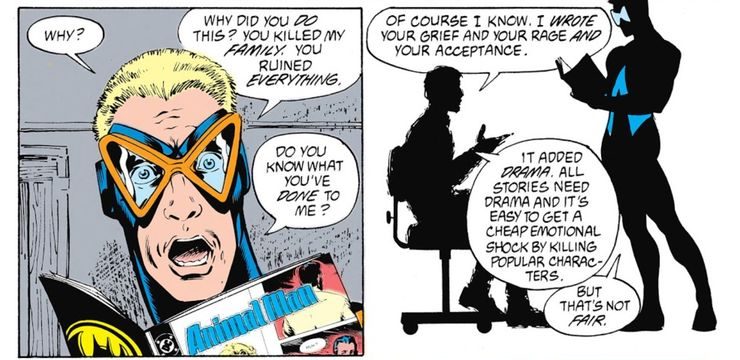

Of course, I would soon discover comics that shared some commonality with Gerber’s Howard the Duck that predated my falling head-over-heels in love with superhero comics in the early 2010s. One of my other all-time favorite comics, Grant Morrison and Chas Truog‘s 1988-1990 Animal Man, is a highly existential fourth-wall burster that ends with Morrison themself appearing on-page. That final issue consists entirely of an extended monologue by Morrison in which they wax philosophical about the nature of fiction and the responsibility of a writer to make their characters suffer for their readers.

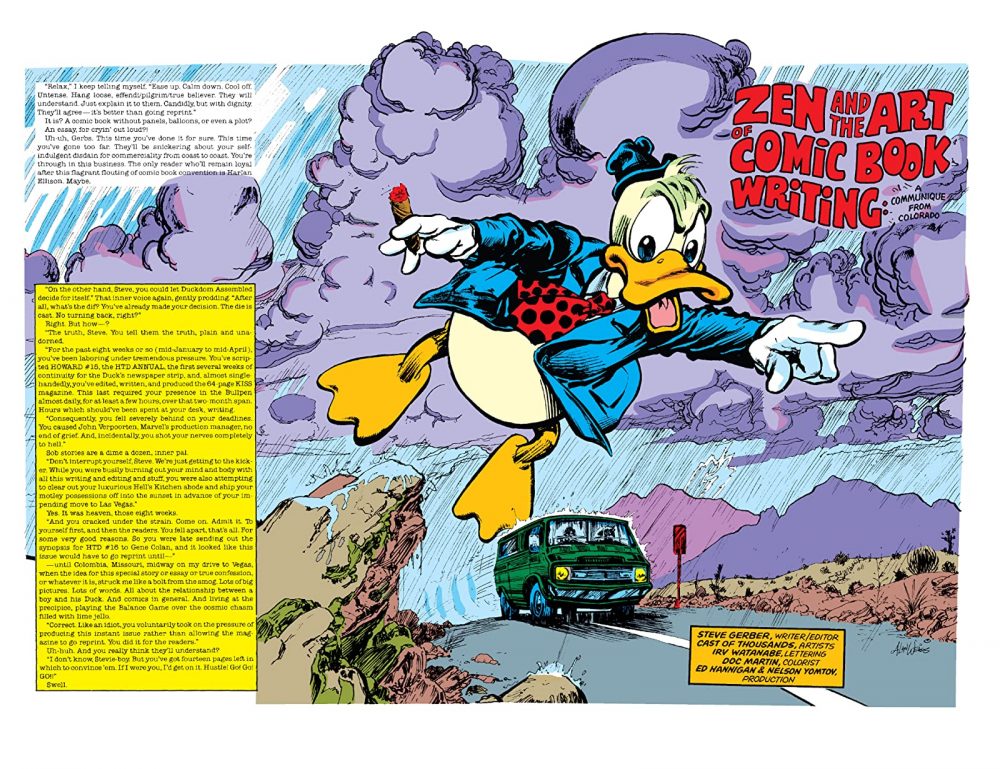

It’s my favorite ending in all of comics, and it’s rightly considered a groundbreaking moment. But it also pairs nicely with Howard the Duck #16. As previously mentioned, Gerber was notoriously bad with deadlines. Finding himself under immense stress between falling behind on his work, moving from New York to Las Vegas, and writer’s block for Howard’s next adventure, he opted instead to write the issue as an illustrated prose essay. There are no panels or word balloons. Howard himself barely appears. To call it metafiction would be erroneous, because while it’s certainly meta, it’s not fiction. Instead, it’s a startlingly vulnerable, if self-indulgent (not necessarily a bad thing) exploration of Gerber’s insecurities.

Gerber was just 30 at the time, the same age I am now. And while our lives and careers are obviously different, I can re-open that issue today and feel as if I’m reading a message from a kindred spirit. I wish I could’ve had a conversation with him, but he died in 2008 at the age of 60.

I’ve mostly been talking about Steve Gerber here, and I don’t mean to discount the incredible artists who made that original run of Howard the Duck a stunning visual achievement as well as a literary one. A bevy of comic book greats contributed to these issues, including inkers like Klaus Janson and Steve Leialoha and colorists like Marie Severin and Tatjana Wood (as far as I’m concerned, Wood is the most underrated colorist in comics history).

And while he may not have joined the series until the fourth issue, Gene Colan anchoring the rest of the series with his moody lines and off-kilter compositions provides the comic’s definitive visual identity. There’s something ever-so-slightly sickly, even sinister, about Colan’s layouts throughout the book. It’s never outright unpleasant; don’t get me wrong, Colan was an incredible artist and you’d be hard-pressed to find a better looking comic from the same era. But Colan imbued every page with the subtle suggestion that something is wrong with the world he was presenting. Was that a comment on the fantastical version of Earth Howard occupies, or the real world that the comic directly satirizes?

Howard the Duck‘s artists deserve as much recognition as Gerber, but I’m a writer, so forgive me for relating most to its writerly achievements. Excuse my grandiosity, but what Steve Gerber achieved with Howard the Duck feels like a miracle. I could hardly imagine a Big 2 comic book writer getting away with what Gerber did today, let alone from 1976-1978 when mainstream comics were still regulated by the Comics Code Authority, and the medium as a whole was still many years away from being considered anything but the lowest of lowbrow art.

When I read Howard the Duck, I get the sense that Steve Gerber knew it would only be so long before his opportunity to write something so bold would be stripped away from him. Howard the Duck is a work of bravery and neurotic creativity, by a writer daring himself to break as many rules as possible before the inevitable yet altogether glorious burnout.

Excellent analysis. I was 14 when Gerber’s Howard came out and it was the perfect vehicle for the rest of my life’s journey.

Once upon a time, Steve had a blog where he posted occasionally. And being that this was the ’90s, personal heroes and famous people hadn’t yet retreated from the waves of online hatred that would one day wash over them… his email address was prominently displayed on the site. So out of the blue, at 30 years old, I wrote him… the first and only fan letter I ever sent to anyone. I told him how much Howard had meant to me, despite having been a pre-teen who probably shouldn’t have been reading the book at all, how he expanded my vocabulary —Howard taught me the word “grotesque”— and how happy I was to have a chance to express my gratitude to someone who’d left his fingerprints all over my brain. Our brief exchange has sadly been lost to any number of mailbox disasters over the decades, but he was incredibly gracious and kind in his response, and took seriously his place as an expander of minds.

FWIW, when I spoke briefly with Gerber at a con in the nineties, I had much the same experience.

Comments are closed.