I’m surprised by my excitement over WandaVision, premiering today on Disney+. The Scarlet Witch and The Vision have never held much appeal for me, neither in their comics source material nor the streamlined Marvel Cinematic Universe versions played by Elizabeth Olsen and Paul Bettany, respectively. It’s not that I necessarily dislike them, but that I don’t know what I’m supposed to like about them.

Yet my interest in the streaming series was piqued when I heard that it would take inspiration from the landmark 2015-2016 The Vision comic book series written by Tom King and drawn by Gabriel Hernandez Walta. Not only is it one of the best superhero comics of the 2010s, but it’s characterized by social commentary and a haunting weirdness that, if the WandaVision creators learned the right lessons from it, could pull the TV drama out of the humdrum formula that’s plagued the MCU for over a decade.

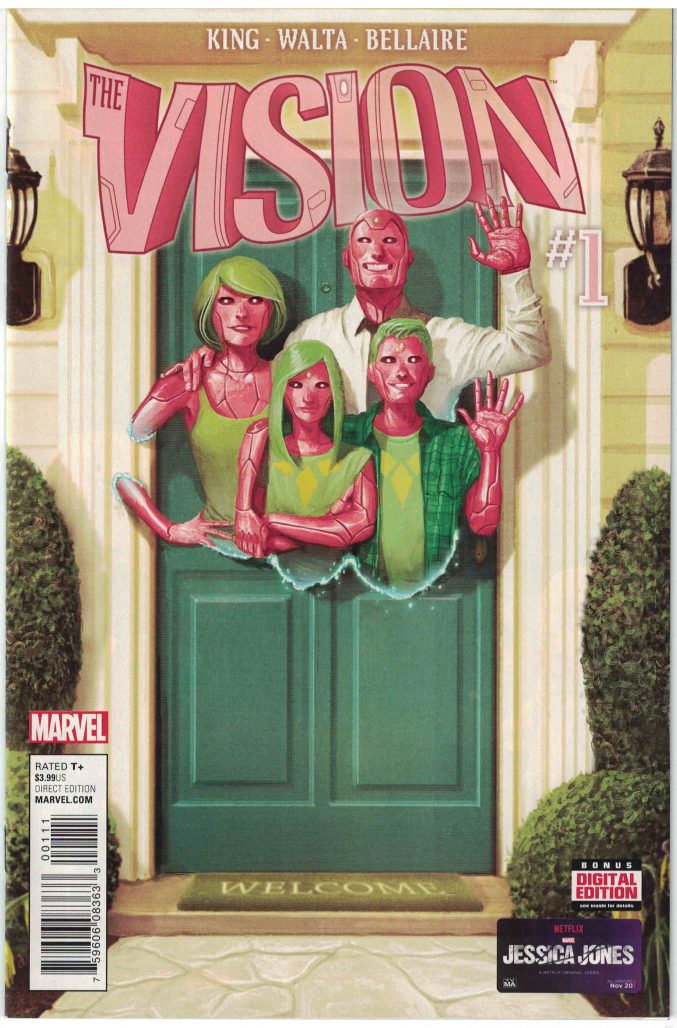

The Vision, which features colors by Jordie Bellaire, letters by Clayton Cowles, and an issue penciled by Michael Walsh, is one of a number of different superhero comics to emerge in the 2010s that were characterized by a lack of traditional superheroics. Charles Soule and Javier Pulido’s She-Hulk falls into this same category, as does King’s own Mr. Miracle with artist Mitch Gerads: recognizable, decades-old superheroes are the stars, but there’s not much in the way of crimefighting or superhero-on-supervillain action.

To borrow the parlance of Matt Fraction and David Aja’s Hawkeye, King and Walta’s The Vision follows the titular android superhero (created by Roy Thomas, Stan Lee, and John Buscema in 1968) on his “days off.” But whereas the former series is characterized by relatively mundane concerns between superheroic action, like adopting a dog and protecting his neighbors from comically predatory real estate gangsters, the latter’s inherently sci-fi-oriented protagonist emphasizes the eerie darkness of his attempts to lead a mundane life.

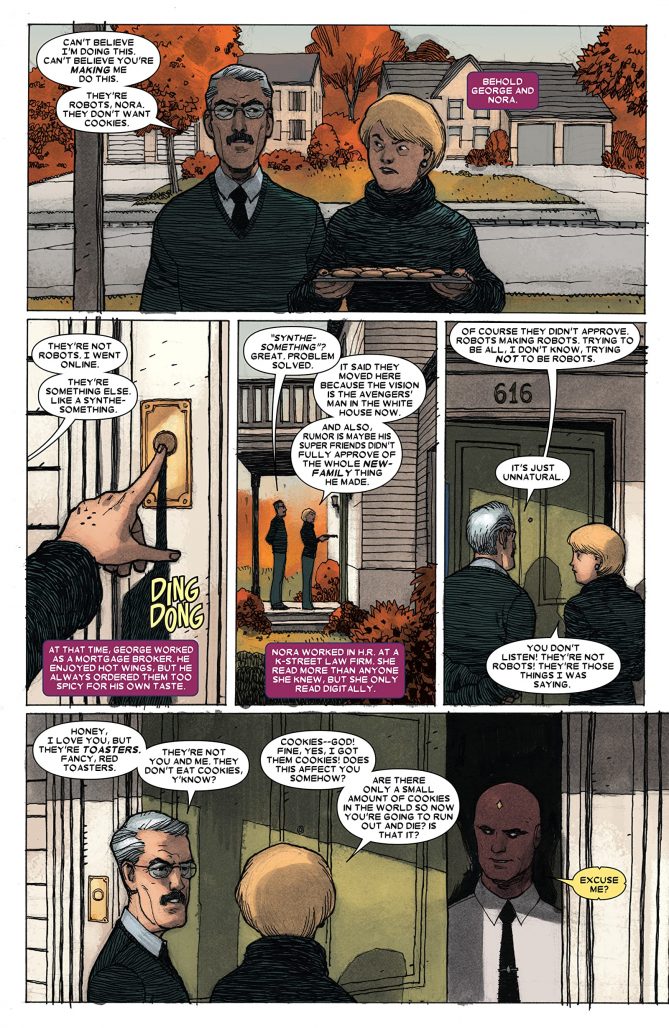

In the debut issue–which a bevy of critics voted as one of the greatest first issues of all time–we’re introduced to The Vision’s new suburban home “at 616 Hickory Branch Lane, Arlington, VA, 21301.” Note that Arlington is just south of Washington DC, so Vision could presumably ride the metro to Tom King’s real residence in the nation’s capitol with ease. What’s more, we’re introduced to three new characters, built by The Vision himself with his own synthetic hands: his wife, Virginia, and his teenage children, twins Viv and Vin.

Readers well-versed in sci-fi tropes a la Frankenstein or The Terminator may expect that The Vision’s family would become evil, or turn on their creator. After all, Vision’s “father,” the supervillain Ultron, turned against his creator, Hank Pym/Ant-Man. (Most people will be more familiar with the movie version of Ultron’s origin, in which he’s created by Tony Stark/Iron Man/Robert Downey Jr., but the general narrative structure is basically the same). Shortly thereafter in the late-60’s pages of The Avengers, Ultron created The Vision as his “son,” and in turn the Vision defied his genocidal father by becoming a good guy and joining The Avengers to defeat his creator.

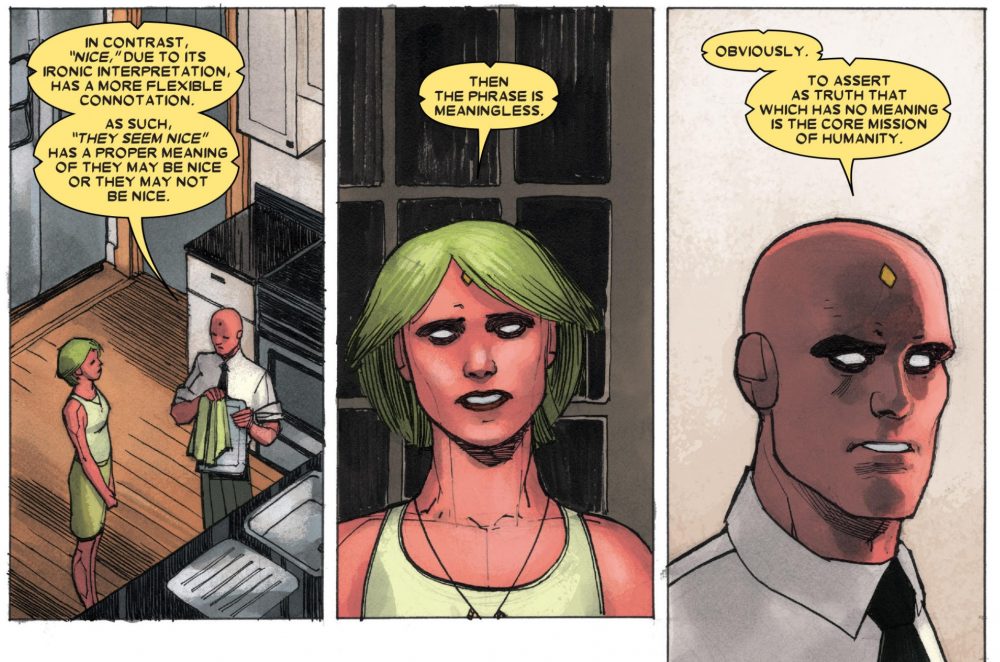

As dark as King and Walta’s The Vision is, rote questions like “can we trust artificial intelligence” and “can robots feel love” have little bearing on the themes of this book. Sure, the Vision family struggles to fit in with their human neighbors who are understandably uneasy about the robots in town who don’t look or talk like “real people.” We, as readers, are immediately confronted by the eeriness of the Vision family, which is often played for uncomfortable laughs. But their essential humanity, in the sense that they experience real emotions like love and grief and embarrassment and anger, are never really in question.

Instead, by juxtaposing an android family with their suburban surroundings, King and Walta illustrate the depressing phoniness of suburban life. The Vision family may be robots, but they’re not as plastic as the white picket fence myth that their human neighbors desperately hang to. It’s a damning portrait of an essential, heartbreaking truth about the American dream: it has to be bought into with social currency. Our attempts to fit into the American ideal that’s sold to us through capitalism and white supremacy are no less robotic than Vision and Virginia play-acting their way through eating cookies with the sniveling middle-aged couple that lives down the street.

One could argue that The Vision is a horror comic. I’m not sure if I’d characterize it that way, but it shook me to my core. I grew up in the suburbs. I’m sure it won’t surprise you that I never fit in. It wasn’t for lack of trying; I didn’t set out to be an outcast. Perhaps I would’ve had an easier time if I embraced how weird my peers apparently thought I was at an early age. Instead I desperately tried and failed to present a synthetic version of myself that would be acceptable to my neighbors, not unlike the Visions studiously trying to present themselves as a typical American family. I wore Aeropostale and American Eagle and Abercrombie & Fitch, but they were hand-me-downs, as that was what my family could afford. I played sports, but I was too clumsy and never enjoyed them anyway. I tried to be funny, but nothing I could say was ever funnier to my classmates than my lisp, which many took as an opportunity to shower me with homophobic and ableist slurs.

“GREG SILBER!” My seventh-grade band teacher once shouted at me in front of the whole class. I was probably reading a book, and was terrified. Ever since preschool, I avoided getting into trouble at all costs, and had no idea what I could’ve done wrong. “MY OFFICE, NOW!”

“What’s wrong?” I asked as I walked in. One of the other band teachers was there, as was my geography teacher. The latter once accused me of plagiarizing a big assignment, telling my parents that my vocabulary was “too advanced” for me to have written myself. It was bullshit, but he was one of the “cool” teachers. I was more disappointed that he didn’t like me.

“Say your name,” my band teacher said.

“G-Greg?” I said, with the sinking feeling that I knew where this was going.

“Your full name,” he insisted.

“Greg… Silber,” I said, lisping the “S” as I always did and still do to this day.

The teachers chuckled and sent me back to my seat, and I quit band (and trumpet altogether) the next school year.

The word I kept coming back to during my adolescence, whether in my journals or, later, in therapy, was “robot.” It didn’t feel as though my peers, or indeed, many of the adults in my life, saw me as a real person. I was a robot put on this earth to amuse them. Mock Greg’s lisp and see how long he can pretend to ignore you until he puts up his middle finger. “Accidentally” knock him into a wall on the way to class, because it’s hilarious and what’s he gonna do, hit back? If you’re lucky maybe he will snap and shout obscenities at you or throw something across the room, and that’s extra fun because faculty will only notice Greg’s outbursts, and then you can play the victim.

I tried to train myself to be stone-faced throughout all this, like a robot. Just going through the motions from one activity to the next, pretending that there wasn’t so much more I wanted to do, so much more I had to say. I saw robot-like behavior in others, too. Keeping up with the latest fashions, repeating the same cruel jokes day in and day out. Did they really think the routine we were forced into was normal? Did they even want to be normal?

This may seem like a weird road to go down in a discussion of a Marvel superhero comic. But suburban ennui is the heart of The Vision. Tom King has proven to be a rather controversial writer, due to both his writing itself and scrutiny of his CIA experience. But I think one reason why The Vision is his most unimpeachable work is because of the universality of the melancholy and trauma it explores at the heart of contemporary society. That it’s a comic about robots and superheroes only underlines how much ghastly cynicism we’re expected to accept on an everyday basis.

If you’re intrigued by WandaVision – heck, even if you have no interest in Marvel whatsoever – King, Walta, Walsh, Bellaire, and Cowles’ The Vision is a must-read. It’s a story that takes an outlandish premise and brings it startlingly close-to-home, in a way that could only be achieved through comics.