The Beat’s Gregory Paul Silber has been accused of having a bit of an… obsessive personality. Each week in Silber Linings, he takes a humorous look at the weirdest, funniest, and most obscure bits of comics and pop culture that he can’t get out of his head.

I love revenge stories. Memento, Oldboy, The Crow, The Princess Bride, pretty much every Quentin Tarantino movie… no matter the circumstances attributed to seeking violent retribution for perceived slights, there’s a reason why vengeance has been a classic storytelling setup since literal ancient times. What is it that makes these spiteful fantasies so timeless?

Let’s get this right out of the way before I go any further: I’m not a vindictive person, and I’m certainly not a violent one. In fact, I’ve been told that I’m non-confrontational to a fault.* It’s likely because of my conciliatory nature, not in spite of it, that I find revenge stories so cathartic. You probably do too, even if you don’t consciously realize it.

(*Ed. Note: Greg has told multiple stories about yelling at people in public. Don’t believe him for a second when he says he’s non-confrontational. –JG)

(*Greg Note: that only happened like twice, Joe! –GPS)

Revenge, at least violent revenge, is not something people regularly engage in. Revenge isn’t rational, and on some level we all know that vengeance isn’t going to do much to improve our lives or the wider world. The magic of revenge as a genre in fiction is that, at its best, it provides the audience with necessary catharsis while acknowledging the profound danger of a vengeful spirit.

Take the John Wick franchise for example, which is probably still the most zeitgeist-y revenge story du jour. That original 2014 film, directed by Chad Stahelski (the erstwhile stunt double for star Keanu Reeves) and David Leitch, thrives on a deceptively simple premise. John Wick (Reeves), a retired but no less deadly assassin, inherits a beautiful dog as a final gift from his wife, as she wanted him to have someone else to love after she died of cancer. A chance encounter with the son (Alfie Allen) of a Russian mob boss (Michael Nyqvist), whom John unwittingly insults, leads to a raid in which the young gangster and his henchmen break into John’s house, beat him up, kill his dog, and steal his beloved car for good measure.

The tone of the first 20 minutes or so of John Wick is startlingly somber for an action movie. It’s not just circumstantial sadness due to the plot as I’ve described it, but the filmmakers make a crucial decision to linger on the sadness, rather than simply anger, in ways few action films allow. The music is melancholy, there are extensive shots of a heartbroken Reeves, and John even cries at least once (how many other action films allow their heroes to openly weep?).

Anyway, I’ve heard many people claim that they refuse to watch John Wick because it seems too sad. You know, the kind of people who regularly visit doesthedogdie.com. And hey, I can’t blame them. Even with it’s well-deserved reputation as one of the most badass (and best) action movies out there, everything I just described sounds like a huge bummer. I know how hard it is to put yourself in the shoes of someone whose dog got hurt like that.

But now imagine what you would do to the person who hurt your furry friend.

That’s the magic of the revenge genre: it allows us to live, for a short time, in the shoes of someone who has the lack of good sense to do what most of us are, quite reasonably, too civilized to do, but all kind of wish we could to some degree. Come on, don’t tell me you’ve never met someone at school, work, or the checkout line at a grocery store who you didn’t, at least for a brief fleeting moment, wish you could go full John Wick on.

Granted, one of the hallmarks of the revenge genre is the theme that revenge isn’t noble, and doesn’t lead to good outcomes for either party. For a pair of films as brutal as Kill Bill Volumes 1 and 2, writer/director Quentin Tarantino’s matter-of-fact approach to this theme gives “the whole bloody affair” its soul.

Kill Bill is the story of The Bride (Uma Thurman), who left a cabal of assassins to marry a decent man, only for the titular Bill (David Carradine) and the deadly men and women of his employ to murder everyone at her wedding. When The Bride wakes up from a coma after surviving the attempted murder, her quest for retribution from everyone responsible for the massacre first takes her to the otherwise quiet suburban home of her rival, “Copperhead” (Vivica A. Fox). After a high-octane kitchen battle ends in Copperhead’s death, The Bride discovers a young girl who just witnessed her mother’s murder. Thurman’s performance during this encounter is subtly regretful, but no less resigned to her mission. “It was not my intention to do this in front of you,” she says. “For that I’m sorry. But you can take my word for it: your mother had it coming. When you grow up… if you still feel raw about it… I’ll be waiting.”

In other words, The Bride doesn’t have delusions of grandeur. She realizes that this little girl is just as entitled to her revenge as The Bride is to hers. The Bride isn’t taking out her family’s killers because she feels it’s the right thing to do, but because, on a primal, id-driven level, it’s something she must do. That’s not honorable, and she knows it. It’s tragic. Both Kill Bill movies are wildly entertaining, with some of the coolest fight scenes ever committed to film, but Tarantino, Thurman, and the rest never let us forget that The Bride’s single-minded quest for revenge is almost as tragic as the bloodbath that caused her to take such a violent path.

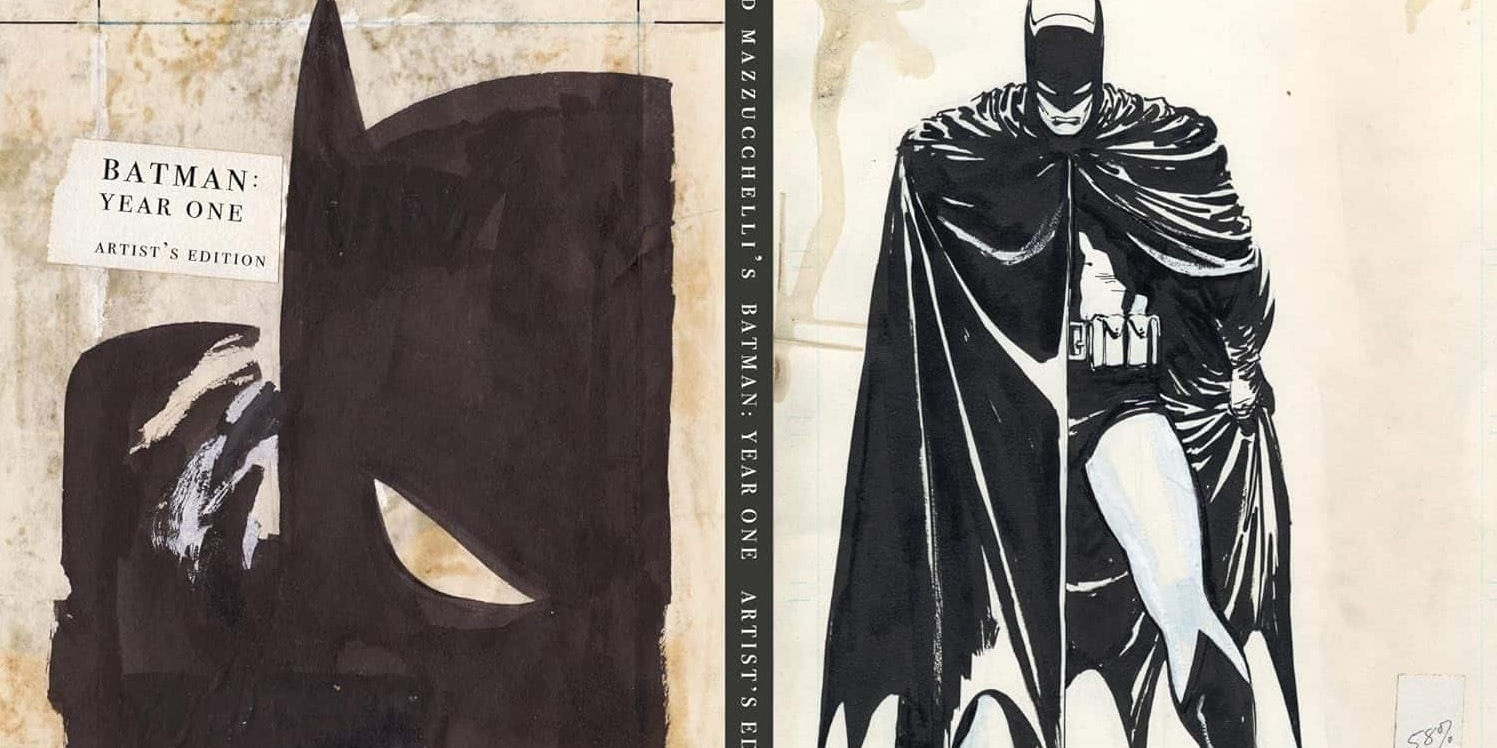

That said, the endgame of a revenge story doesn’t have to be murder, as we’ve seen from comedies like Mean Girls. And even when the vengeance is violent, that doesn’t mean the avenger (heh) must go so far as to kill their enemies. It’s one of the many things I love about Batman. That new Robert Pattinson movie liberally borrowed the “I am vengeance” catchphrase popularized by Batman: The Animated Series, and indeed, Batman has always been driven largely by his desire to avenge the spirits of his murdered parents.

That’s why Batman’s never-ending “war on crime” is so quixotic. There’s no specific figure Batman is exacting vengeance against, but rather the cruel state of the world that allows a child’s parents to be murdered before his eyes. It helps, then, that as much as Batman is no stranger to kicking butt, he has a strict code against killing. Ben Affleck‘s shirking of this code was a dealbreaker for me in Zack Snyder‘s Batman V. Superman, so one of my favorite things about The Batman was that as much as this version of The World’s Greatest Detective wasn’t afraid to beat bad guys to a pulp, he made more than one speech about why murder crosses a line.

Granted, the one seeking vengeance in revenge stories isn’t even the protagonist much of the time. There are some who’d argue those don’t count as true revenge stories, but I’m not sure I agree. When it comes to Wes Craven‘s original 1982 A Nightmare on Elm Street, you’d be hard pressed to find many people who’d argue that Freddy Krueger (Robert Englund) was, like, morally correct for murdering teenagers with his needle gloves. We’re talking about a man who was burned alive by local townspeople because he was a child murderer, who in turn takes revenge from beyond the grave by… murdering more children. Freddy, buddy, you do realize that the problem here is you, right?

While we (hopefully) don’t identify with Freddy murdering all those teenagers, revenge is absolutely a core theme of A Nightmare on Elm Street. A pivotal scene in which “final girl” Nancy Thompson (Heather Langencamp) confronts her mother (Ronee Blakley) about the adults in town keeping Freddy’s violent death decades prior a secret from the kids in town reveals the sordidness of the crime. It’s not that Nancy is sympathetic to Freddy, far from it. After all, he’s been killing all of Nancy’s friends and stalking her in her dreams. It’s that, in taking justice into their own hands and trying to shelter their children, the parents unwittingly cursed them children to suffer the consequences (at least in that first film, Freddy, the boogeyman figure that he is, never targets adults). In that way, Nightmare plays with a similar theme as Kill Bill: adults get to play hero with mob justice, but it doesn’t prevent children from inheriting the trauma. The fact that Freddy is obviously in the wrong for being mad at the townsfolk for killing him after he butchered all those children isn’t the point.

Of course, Nightmare ends with Nancy exacting her own extremely justified revenge against Freddy (if you haven’t seen the film, I assure you, this is not a universe in which the problem could’ve been resolved with Freddy going to jail or whatever), and that’s extremely satisfying in its own way.

But my point is, revenge stories work largely for their simplicity as they strip storytelling down to its barest essentials. The central characters’ motivations are clear, it’s easy to tell who we’re supposed to root against, and the why of it all is rarely in question. But just because revenge stories may not have subtlety, doesn’t mean they can’t have nuance.