The Beat’s Gregory Paul Silber has been accused of having a bit of an… obsessive personality. Each week in Silber Linings, he takes a humorous look at the weirdest, funniest, and most obscure bits of comics and pop culture that he can’t get out of his head.

“Biff! Pow! Comics aren’t just for kids anymore” has been such a cliché for so long that it was already a cliché by the time Scott McCloud poked fun at it in 2000’s Reinventing Comics. Adult readers are familiar enough with that style of clueless, perennial headline that it’s become a meme among the community. Yup, comics – that medium of combining words and images which has been around in some form or another since ancient times – are not strictly for people whose brains have yet to fully develop. Somehow, that’s still shocking for legions of old-fashioned snobs in 2022.

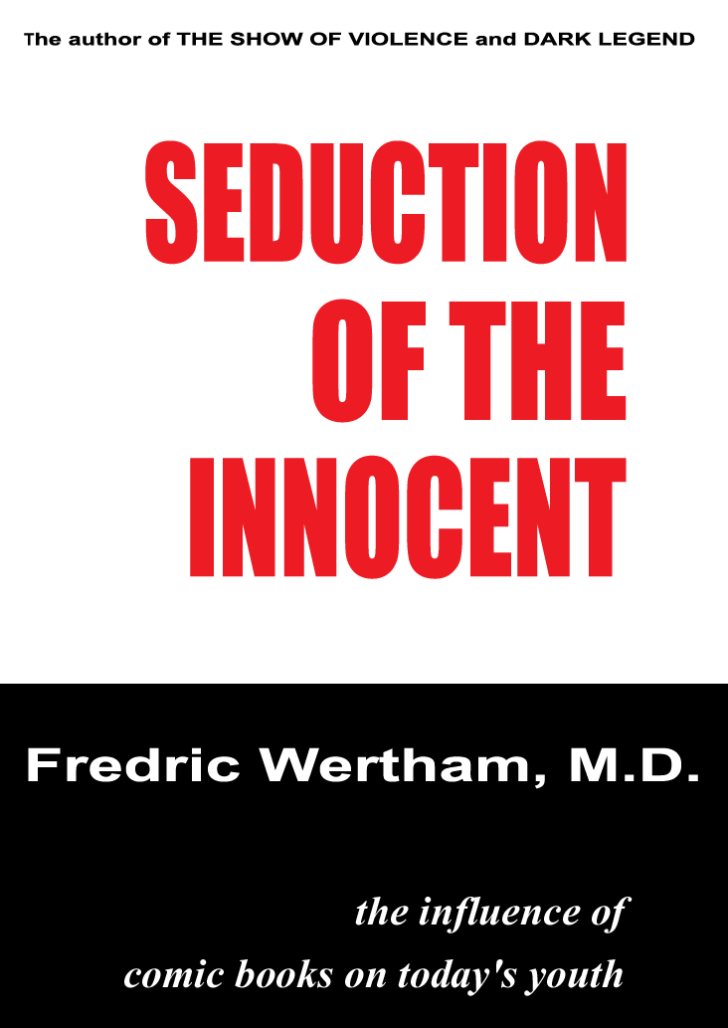

In a lot of ways, grown-up comic readers are right to have a chip on their shoulder about their hobby. For one thing, I don’t believe our culture has fully shaken off the 1950s moral panic spurred in part by Fredric Wertham, Seduction of the Innocent, and the US Senate hearings that led to the shuttering of EC Comics and the creation of the censorial Comics Code Authority.

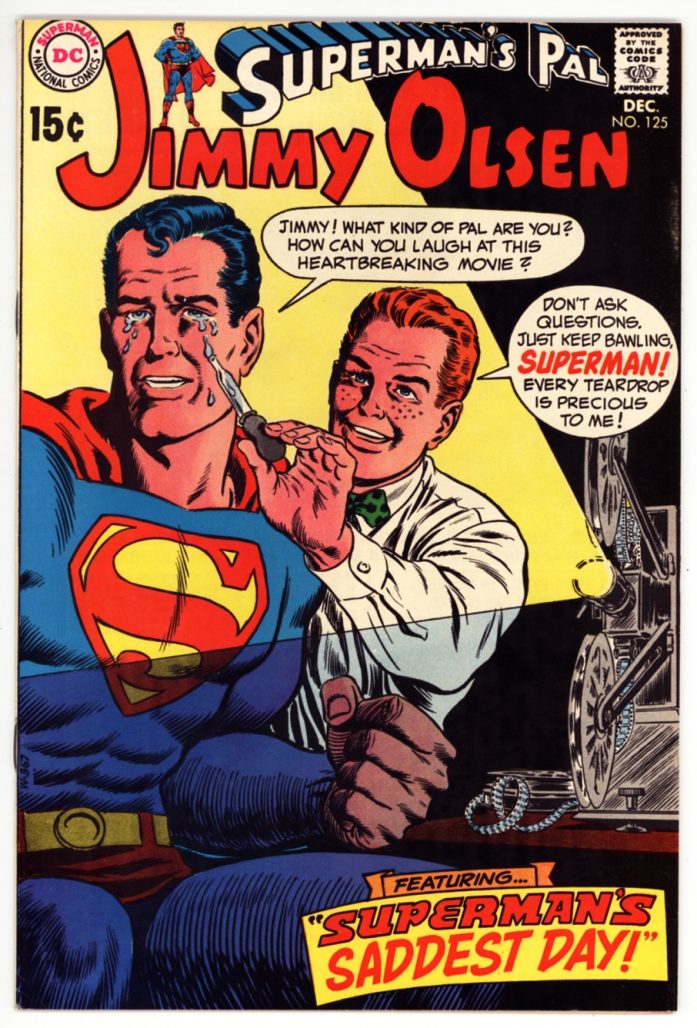

The CCA had its own role in perpetuating the myth that comics are just for kids – and not particularly smart or well-adjusted kids, at that. It effectively codified that notion by enacting strict guidelines beyond predictably risqué content like sex, violence, and drug use. The criteria included clauses like “if crime is depicted it shall be as a sordid and unpleasant activity,” and “in every instance good shall triumph over evil and the criminal punished for his misdeeds.” In other words, there was very little room under the code for comics that depicted moral gray areas, or really any story with thematic ambitions beyond “good things are good and bad things are bad.”

During the Silver Age, at which point The Code was at the height of its influence, there were plenty of creators who found clever workarounds to sneak in whatever degree of complexity they could get away with before the CCA relaxed its guidelines in the Bronze Age. But let’s face it: thematic depth isn’t the selling factor for comics of that era. That’s not to say they’re stupid, just that they had other ways of being entertaining and memorable. You couldn’t be lurid under the Code, but there was nothing stopping creators from getting weird. It’s true that the CCA essentially forced superheroes to become the dominant comic book genre, which many would argue held the art form back for decades (both can be true: superheroes are my favorite genre, and the comics reading/making community needs to look further beyond its obsession with superheroes). But an underrated, if unintentional, result of The Code is that to this day, there isn’t another artistic medium as consistently willing to go cuckoo bananas as comics.

Anyway, the Comics Code Authority is dead, but its societal influence is still shuffling about, shaking its fist at the kids on its lawn. There are still those who think “comics will rot your brain” (as at least one person my own age has told me with a straight face). Sure, that kind of ignorant attitude is fading as more and more mainstream entertainment is adapted from comics, and genre fiction in general has become much more acceptable among the mainstream in recent decades. But still, many of us are old enough to remember when things were different. When I was a second grader in the late 1990s, my teacher screamed at a classmate for reading a comic he brought from home during silent reading time. “This! Is not! A book!” she roared.

Generations of comic book fans grew defensive. Some leaned into comics’ outsider status with the underground “comix” movement of the 1960s and ’70s, which ignored mainstream distribution (thus ignoring the Comics Code Authority) and were instead a hit among hippies and stoners at head shops. Others latched onto respectable terms like “graphic novels” and “sequential art” (both coined by the great Will Eisner). By the 1980s, whether readers preferred the outlandishly provocative underground stylings of R. Crumb, or the more sneakily subversive Uncanny X-Men comics written by Chris Claremont, comics fans were chomping at the bit to show the world that comics are just as artistically rich and literary as any other medium. That decade brought us iconic works like Watchmen, Maus, and The Dark Knight Returns, all of which were hailed as exemplars of the art form. They still are to this day, and indeed, they’re among the few comics that are beloved by scores of normies who actually read them.

I love all those comics to varying degrees, but, and I’m not the first one to point this out, the industry and readership largely learned the wrong lessons from those masterworks. Alan Moore comics aren’t great because his characters bleed, curse, and get naked, but because he respects the medium and his readers’ intelligence. But it’s hard to convince those who won’t touch comics that we’re not big dumb babies for reading comics. It’s especially hard to convince the comics-skeptical that there’s any artistic or literary merit in colorful magazines about spandex-clad strongmen facing off against villains with names like “Doctor Doom” and “Captain Boomerang.”

It’s easier to shove the lurid and profane in their face. “See? How can you think comics are for kids when people are getting their arms ripped off?”

Superhero comics for adults are not the exception anymore. For almost 40 years, they’ve effectively been the rule. I’m not a parent, but if you are and you read superhero comics regularly, I’m genuinely curious: what percentage of contemporary Marvel and DC titles would you feel comfortable letting your child under, say, eight years old read? I’d wager it’s less than half.

I think that’s a shame. Enough time has passed that we no longer need to convince the world that “(superhero) comics aren’t just for kids anymore.” Those who still don’t get it never will. Instead, we should be celebrating superheroes as a rich, vibrant genre for children… that adults can enjoy too, of course.

While we’re at it, this goes for non-comics adaptations of superhero comics, too. It’s silly to me that a bunch of Batman fans on social media were apparently disappointed that the upcoming Robert Pattinson-starring The Batman will be rated PG-13 rather than R. Batman is a children’s character, so even PG-13 is a stretch despite that being the standard for superhero movies since that Michael Keaton movie in 1989. There’s a place for R-rated superheroes; Logan is one of the best superhero movies yet. But I’m not impressed with Deadpool or Joker just because they’re rated R.

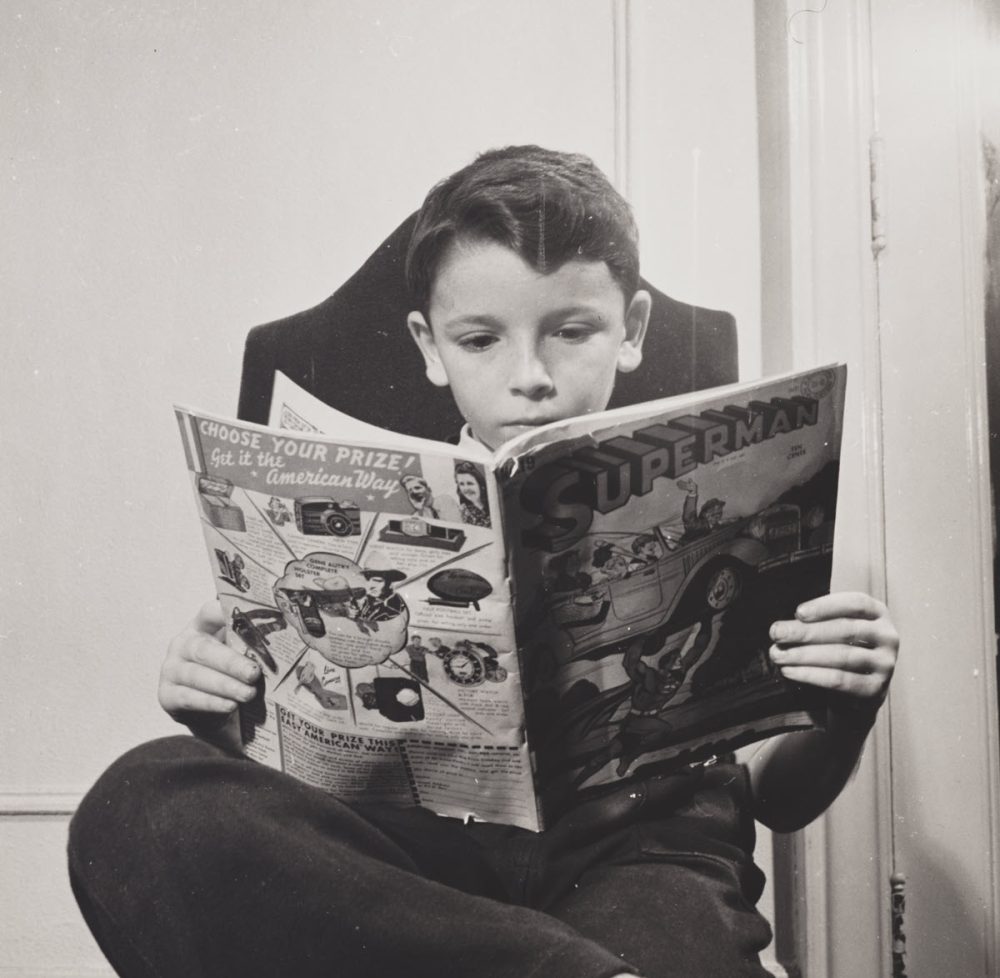

Please understand that I’m not prude or puritanical. I’ve sung the praises of violent, sexual, and generally not-for-kids superhero comics countless times throughout my criticism career, including in this column. I wouldn’t want adults-only (or adults-and-teens-only) comics to stop being made, and I’m certainly not calling for censorship. What I am saying is that superhero fandom at large needs to get over itself. Accept that superheroes have been made for children since Superman debuted in 1938. Accept that you don’t have to enjoy superheroes any less now that you pay bills.

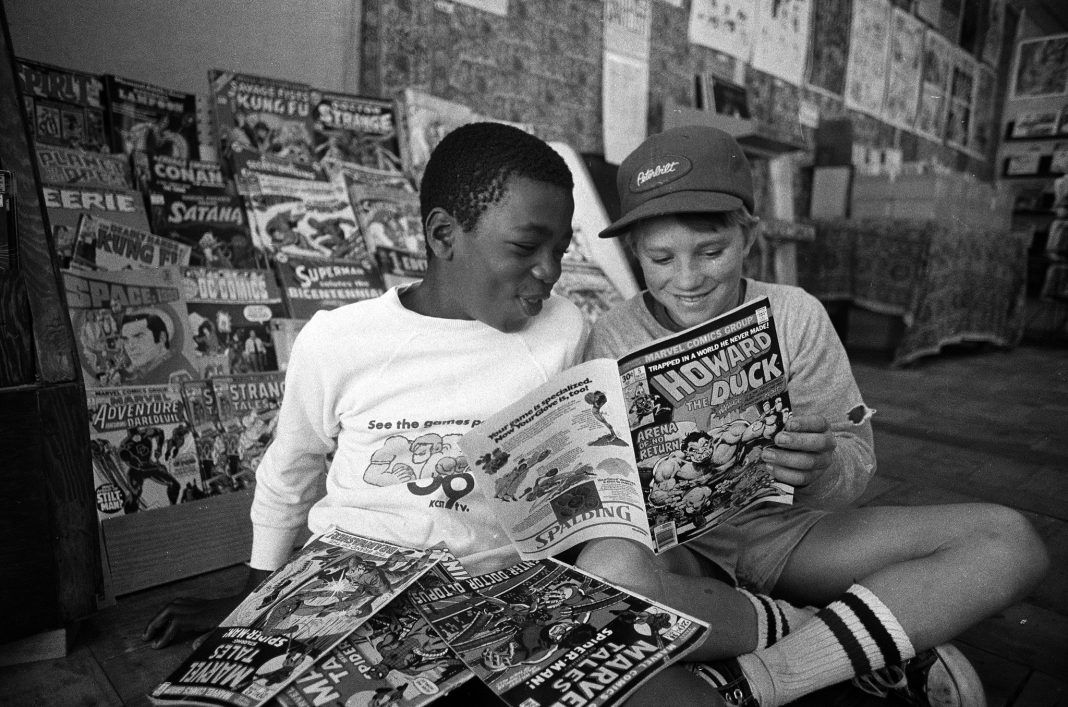

If you’re bristling at any of this, I urge you to think back on how you first fell in love with superheroes, even if, like me, you weren’t reading comics at the time. Maybe it was a cartoon, or a movie, or a video game. But with few exceptions, you were almost certainly a child. Personally, I don’t even remember my first exposure to superheroes. They were always there for me. Some of my earliest memories include Power Rangers and Batman.

What did you like about superheroes as a kid? The action-packed adventures and fantastical storytelling had to be part of it, sure. That goes without saying. But how did superheroes make you feel? If you were anything like me, they probably provided valuable power fantasies at an age when you felt powerless.

There’s a lot to be said for the ways in which superhero stories deliver morals, too. Yeah yeah, we all know our parents and teachers want us to be honest, brave, kind, and generally decent people. But an underrated part of the magic of superheroes is that they make being a good person seem like the coolest thing in the world. In the world of superheroes, good people are strong, tough, and always win against the bad people. Don’t underestimate how important that is for kids as they first get a sense of the world.

Those values don’t become any less important as we grow up, even as we learn, with great sadness, that the lines between good and evil aren’t as clear-cut as we wanted to believe, and that sometimes the bad guys even win. When I’m at my lowest thinking about the wretched state of the world, or even just my own life, I still turn to superhero comics for hope and inspiration. Daredevil doesn’t give up, so why should I?

I should acknowledge here that the past several years have seen a rise in superhero comics, including from the Big 2, explicitly geared towards children, and I hope that trend continues. Marvel had great, well-deserved success with Ryan North and Erica Henderson‘s The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl, DC published one of the all-time great Superman comics with Gene Luen Yang and Gurihiru‘s Superman Smashes the Klan, and Dav Pilkey, whom I grew up with via his infamous Captain Underpants books, now is delighting a whole new generation of young readers thanks to Scholastic’s Dog Man, consistently one of the best selling graphic novels.

There are many other kids’ superhero comics I’d wholeheartedly recommend to readers of all ages, although I’d understand if they’re not every adults’ style. That’s fine. I’m not asking adult superhero fans to change their tastes or reading habits. All I’m asking is for you to allow yourself to make peace with the fact that these characters you love and grew up with belong just as much to a new generation of superhero fans as they did for you. You’re an adult. That means you’ve earned the right to enjoy what you enjoy without guilt or the need for apology (uh, within reason). Straining to convince others of your own maturity is childish.

Will Eisner did not coin the term “graphic novel.” Richard Kyle did, in 1964.

Why is Batman a children’s character? He’s a fictional character but why are you limiting him to ‘jusyt’ a children’s character?

The conceit of this article is that as a child you were attracted to comics because of the superhero action, and while that may be somewhat true, it wasn’t what sustained my interest for very long. I quickly discovered that comics were extremely subversive and that’s what I ended up staying for. I was a weird kid. I was seeking out weird stuff and comics fit the bill. Who cared if Spider-Man was fighting the Green Goblin when I could see the Maxx attempting to help his friend Julie work through her trauma, or the gothic horror and new takes on mythology of The Sandman, or the subversive humor of Hate and Eightball, or any of the rigorously drawn comics of the time made for more mature audiences like Sin City or Acme Novelty Library? Or Vertigo Comics as a whole? That’s the stuff I found between 9-14 years old and that’s what I was after. I actually didn’t even start really reading regular superhero comics until 2000 or so when I saw that Marvel was poaching Vertigo talent to come work on X-Men and Punisher comics and I was almost done with high school by then.

When I was a kid most media was intended for adults and if kids liked it too, that was just a bonus. Look at blockbuster movies prior to the mid 90s (Terminator, Robocop,Alien, Predator, etc.) or even the content of cartoons in the 90s like The Simpsons or Ren & Stimpy. Now everything is made for kids and it’s boring.

Comments are closed.