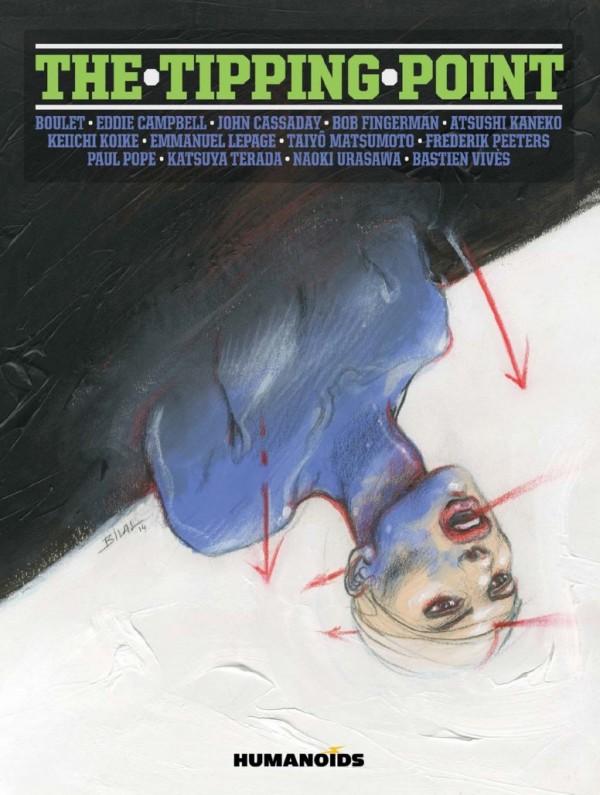

Part of the celebration of 40 years of international publisher Humanoids, this anthology gathers some great talent to explore the idea of forks in the roads, those moments of life discovery that are like Schrodinger’s Cat for human emotion. As with any anthology, the results vary, but there’s a lot of good here, particularly considering these are all short works that don’t have a lot of space to get across the simplest ideas. It’s a real treat when complicated ideas find their way into these pages.

The Tipping Point opens with Taiyo Matsumoto’s “Hanako’s Fart” uses the passing of gas as a world wide marker for a number of different experiences across different cultures. It’s a slight bit of poetry, but it’s presentation of personal experience as the definition of reality takes the mundane into science fiction terms. We are all alternate universes, separated our insular experience yet connected through existence.

This is an approach that defines the best work in rest of the book, filled with entries that address big ideas in small moments, some better than others, but many touching on the notion of separate people and spaces as far removed sections of a multiverse.

In Emmanuel Lepage’s “The Awakening,” a spark of sexuality during childhood manifests as an abstract spring to consciousness inside a new universe, wrought through realistic black and white washes that take on an eerie patina. The same tone is in Eddie Campbell’s “Cul de Sac,” which has Campbell searching a new neighborhood for a lost cat, existing like an other dimensional phantom within the new landscape.

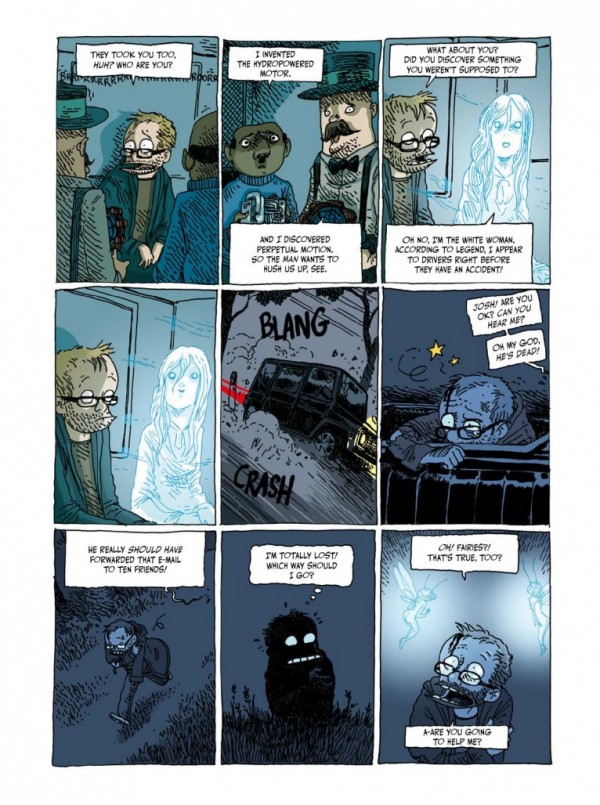

Bob Fingerman’s “The Unbeliever” takes a more common form of denying other worlds — an atheist — and takes him on a path designed to mess with his mind. If the conclusion seems obvious, it’s a punchline delivered with perfect timing followed good-humored sarcastic lead-up. There’s something about the story itself that reminds me a lot of the ancient DC Comics series, Plop. Boulet’s “I Want To Believe” travels similar territory, instead focusing on skepticism in regard to pseudo-science and urban legends, and arrives at a potent punchline following a flurry of encounters with things that patently do not exist.

Some entries seem like previews of larger works. Paul Pope’s “Consort to the Destroyer” is an exquisitely wrought action piece, following the battles of “the daughter of the mountain.” I’m not sure it adds up to much, but it carries a mystique that makes you think there is more to come. It’s the same for Bastien Vives’ “The Child, “a brief tale of outer space horror that portrays its incident well in blacks, whites, and grays, but leaves off at a moment that begs for more story, and Frederik Peeters’ “Laika,” which reads like a particularly enthralling prelude to a clever and longer science fiction horror tale.

There are at least two mind-blowers at the end of the book, relying more on visual poetry via cluttered psychedelia than straight narrative. Keiichi Koike’s “Fish” throws in elements of world destruction in relation to our oceans, mixing images of apocalypse that hearken to Fukushima and climate change with Moorcockian science fiction imagery. Katsuya Terada’s “Tegu” takes a similar approach, using Japanese mythology to investigate the cartoonist’s relationship with his own page.It’s hard to know what that one adds up to, but it’s a crazy enough ride.

A few stories are well-intentioned and expertly-crafted, but left me unmoved.

Atushi Kaneko’s “Screwed” is a frantic, brief depiction of the possible end of the world, connecting the dots of hostile masculinity in a Kubrickian way. Lit in a pale yellow wash, it could have used more pages to flesh out its purpose and statement. That males are angry and warlike isn’t much of an observation. John Cassaday’s “Huckleberry Friend” is equally brief in what it has to say, depicting Huckleberry Finn contemplating whether he should turn in his slave companion Jim, and wrestling with compassion and the idea of what is right. Meanwhile, Naoki Urasawa’s “Solo Mission” sets up a comedic space adventure against the backdrop of family expenses, but the punchline fizzles.

The more important aspect of this collection, as stated by publisher Fabrice Giger in the introduction, is well-achieved. Noting Humanoids’ mission to “build bridges between American comic books, Japanese manga, and European bande dessinee,” the comics that follow brag to the success of the company in achieving this. Much like the concept that we are all alternate universe, so it seems with the individual creators in international cartooning, but with commonalities in style and presentation that are striking.

Far from just building bridges, this anthology shows Humanoid mapping the points where the alternate universes begin to resemble each other, and showing that there is some harmony and grace within the multiverse of cartooning, and even separate universes might in fact build off each other.

“It’s the same for Bastien Vives’ “The Child, “a brief tale of outer space horror that portrays its incident well in blacks, whites, and grays, but leaves off at a moment that begs for more story…”

That sounds pretty much like every Vivès comic I’ve read. The man is immensely talented, but needs to seriously work on his endings.

Comments are closed.