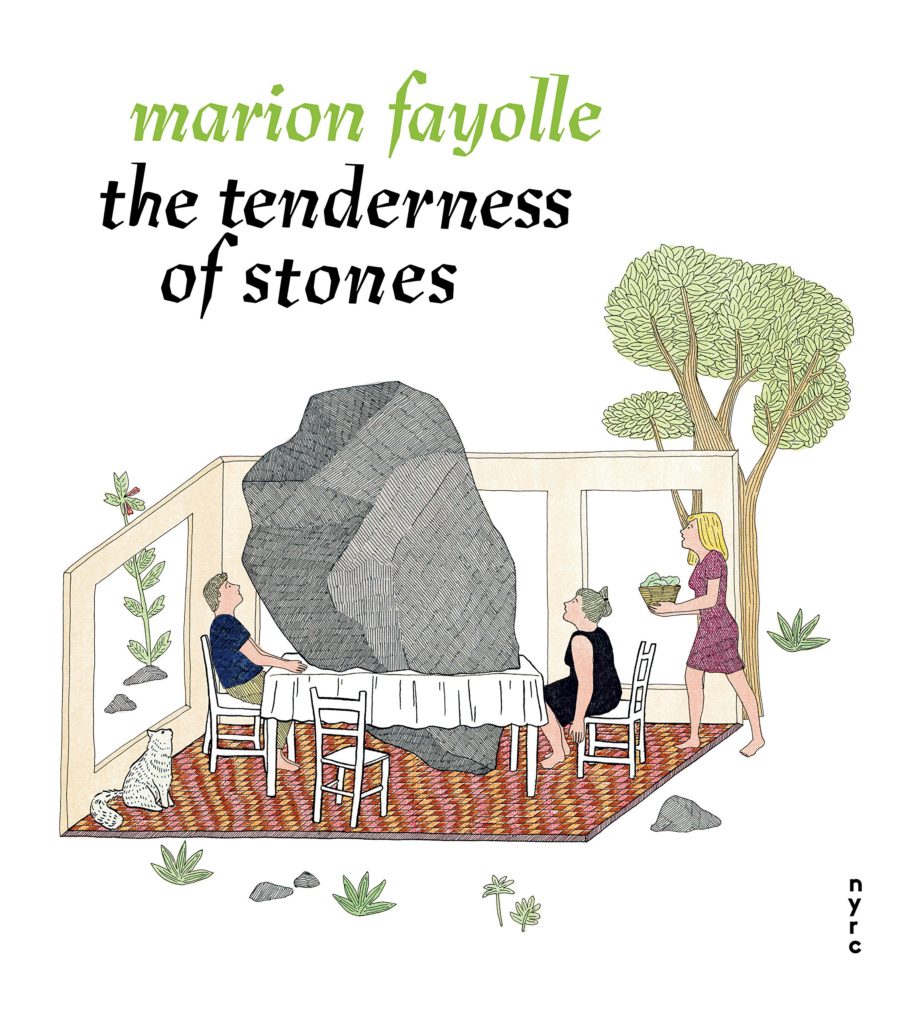

The Tenderness of Stones

The Tenderness of Stones

Cartoonist: Marion Fayolle

Translation: Geoffrey Brock

Publisher: NYRC New York Review Comics

The Tenderness of Stones is a difficult book to read. It’s the story of a family caring for their father, who’s suffering from a debilitating terminal illness, and how they are and aren’t coping with it. It’s about loss, but it’s mostly about the conflicting feelings surrounding loss. It’s about all of the contradictions brought about when a loved one is on their way towards passing. Sadness, relief, pain, anxiety, melancholy, regret — these are some of the things you feel at someone’s passing after a period of sickness. Sadness at having to deal with their health issues. You feel sad that they are suffering, that it makes you suffer too. Relief that it will soon be over for them, and for yourself. Pain that you have to see them this way, pain that you have to deal with them this way too. Regret that you will lose them, and regret that you feel all of these conflicting feelings.

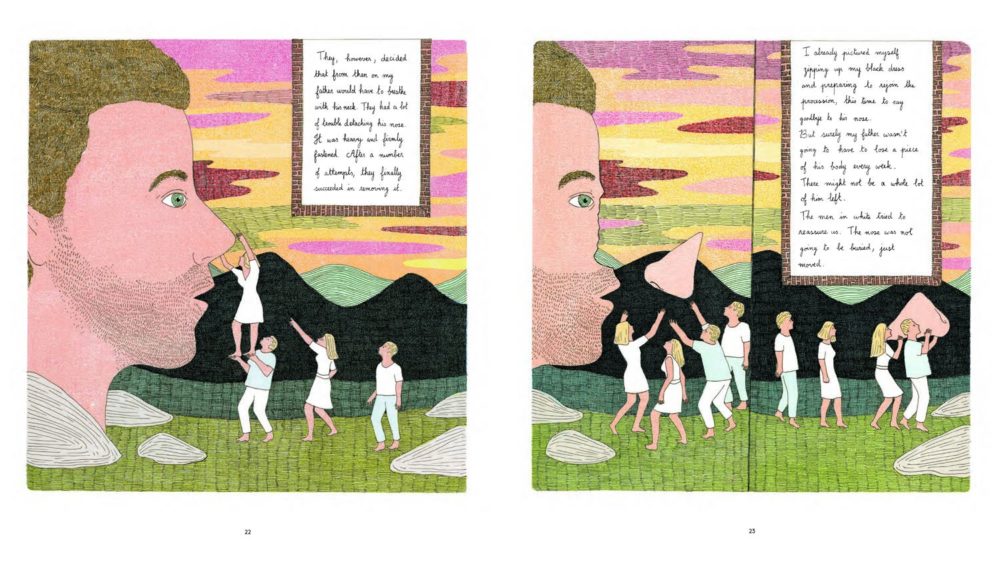

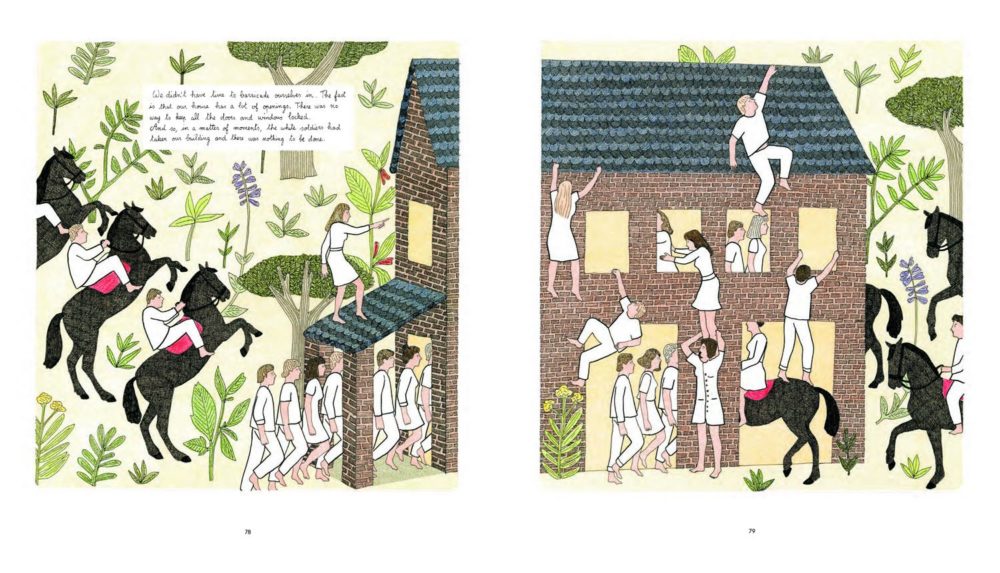

In this context, The Tenderness of Stone, Marion Fayolle‘s second English work (and the first since Nobrow’s 2013 translation of In Pieces) is a thinly veiled metaphor for death and grief. Her father, suffering from a lung cancer, becomes a stone, a giant boulder for the rest of the immediate family to carry. Her father becomes a baby demanding constant attention. He becomes an ignoble king, reigning on his family and forcing them to obey his every whim. He is a rough, rugged cliff, whose family must climb, even as their hands get bloody and sore. Here Marion Fayolle uses all of these analogies to talk about her ailing father and the impact it had on her family. My colleague John Seven had a comprehensive review of this book in September, but I wanted to discuss it further. The Tenderness of Stones is not only a personal book for me, but I felt there was still more to discuss. I’ve even attended the Enemies of the State Book Club discussion on it with Rob Clough over at Solrad.

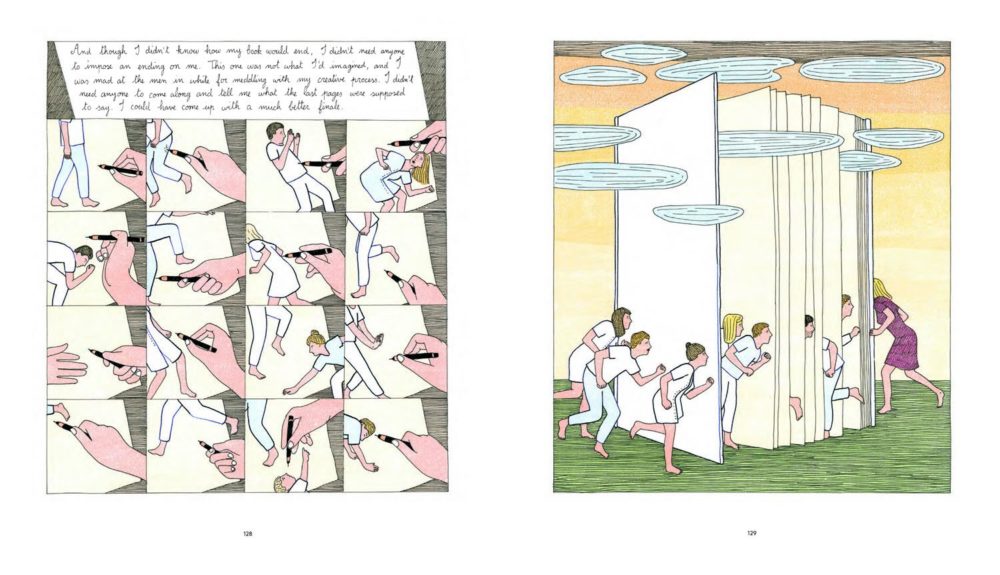

What’s interesting to note about Marion Fayolle, and The Tenderness of Stones in particular, is that she uses a free, improvised approach to her work. In her thesis Écrire des images (Writing images), of which some excerpts is available on her website, she explains that when she makes comic books,

“[…] there is no synopsis, no defined path. I take some short notes, but I only see images. I don’t start from a text, or the need to say anything specific to illustrate. I function backward. I start from an image, an illustrated metaphor, and then it’s animated, I justify it and eventually, the stories make sense… My writing process is closer to improv theatre.”

This explains why her stories are so personal, she doesn’t need to focus on her story, the images are ingrained in her head and she can easily transfer that to the page and write the story that goes with it, rather than illustrating her story. Her crosshatching images and figures come to her before the story does. The words she writes in cursive comes after.

That improvisational approach is certainly odd, and probably wouldn’t work as well as it does here if the story wasn’t so personal. In 2018, my mother passed away from pancreatic cancer. She was diagnosed on March 28 and passed away 4 weeks later. During those four weeks, I was at home with her and became her primary caregiver. I remember catching her the first time she fell, helping her go up and down the five stairs from her room to the living room, lifting her fork when she became so weak she couldn’t do it herself without shaking. During her last week, we found her a room in a palliative care home. I’ll remember exactly how it felt and what the adapted transport, a white minibus, came to pick her up and bring her in a wheelchair to the “Centre d’hébergement Charlesbourg.” How it was when the driver moved her wheelchair down the front lawn. She had an uneasy smile across her face, knowing it was the last time she would ever be in her house. These images are burned into my mind. These traumatic images stay with you, they leave an indelible scar. Fayolle using those moments, those images as a starting point for her book made complete sense. The strength of those images is undeniable and her ability to capture it in such an ethereal manner was inescapable.

But beyond the personal aspect of The Tenderness of Stones is a very nuanced way to approach the process of grief and loss. Fayolle here reaches for both the lighter and darker aspects of being a caregiver to a family member. It’s difficult to see a loved one going through something so difficult. She manages to talk about how she felt she could use the opportunity to help care for her father as a way to get closer to him, while at the same time, feeling trapped by him, like her agency has been substituted by that of her father. It’s a tough balance to strike without sounding too ingrate, mean or naive, but Fayolle manages to carefully illustrate this situation in all of its complexities and contradictions.

I’ve mentioned regret earlier; it’s another thing that reoccurs throughout this book. She regrets not having had the chance, or the ability to know him more. This is beautifully illustrated by Fayolle, who erects a giant statue of her father in black stones. She tries to pin pages with colour to make him whole, but there are too many pages missing. She regrets that the book’s ending is preordained. If it were up to her, the ending would be different, but reality has different plans. She regrets not being able to find closure with him, few rarely do. The book in itself is the closure, but she’s not sure that this is satisfying either. Grief is complicated.

The Tenderness of Stones is a fantastic graphic novel about loss and everything surrounding loss. If you’ve ever had to grieve the loss of a loved one, or had to take care of an ailing family member, this book will speak to you. And if you haven’t, the pain of loss will be coming to you eventually, and you’ll feel just as sad as the rest of us.

The Tenderness of Stones

The Tenderness of Stones