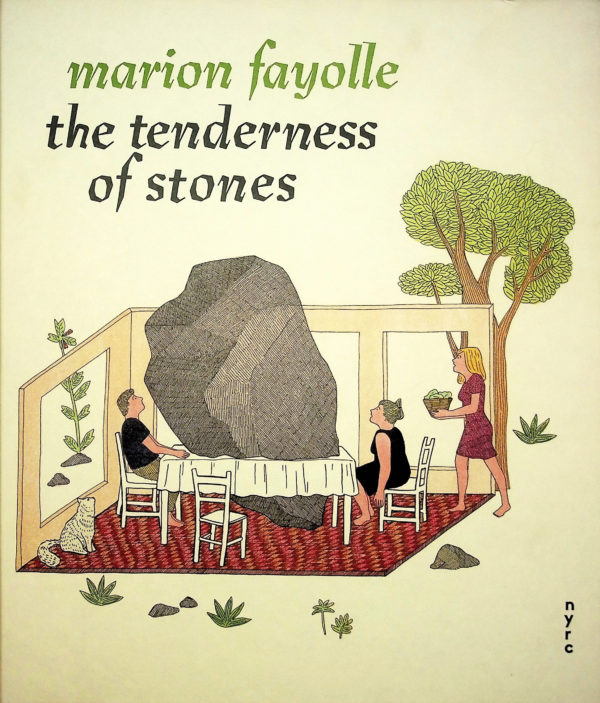

The Tenderness of Stones

By Marion Fayolle

Translated by Geoffrey Brock

English lettering by Dean Sudarsky

New York Review Comics

The Tenderness of Stones is not a quick read, nor is it a very cheery one. French cartoonist Marion Fayolle takes a storybook approach to the stages of loss within a family, a surrealist vision of caregiving and the dark emotions that run through the heart of those surrounding a dying family member.

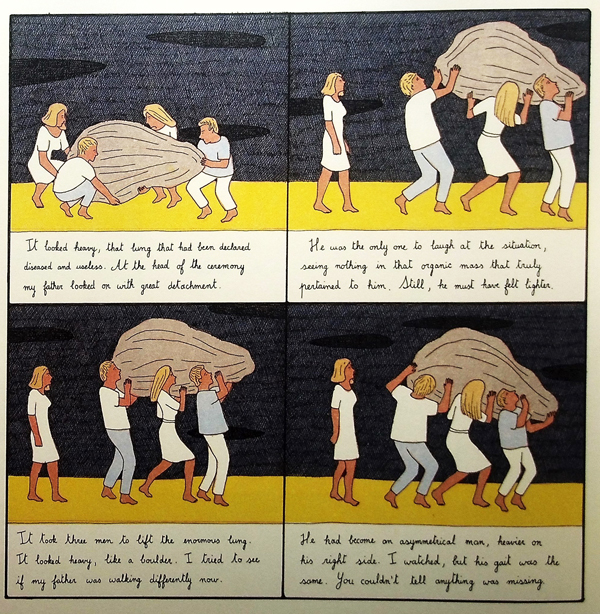

When the book begins, a giant lung has been removed from the father, who hides and watches as they perform a funeral for the body part. The burial isn’t easily rendered, but instead requires a lot of physical labor on the part of the family, most notably just carrying the lung, which is almost bigger than the four other family members combined.

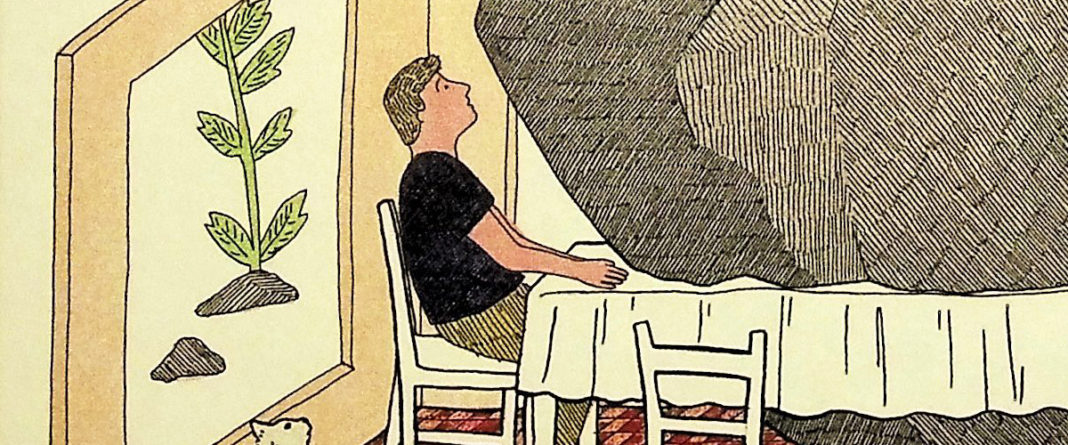

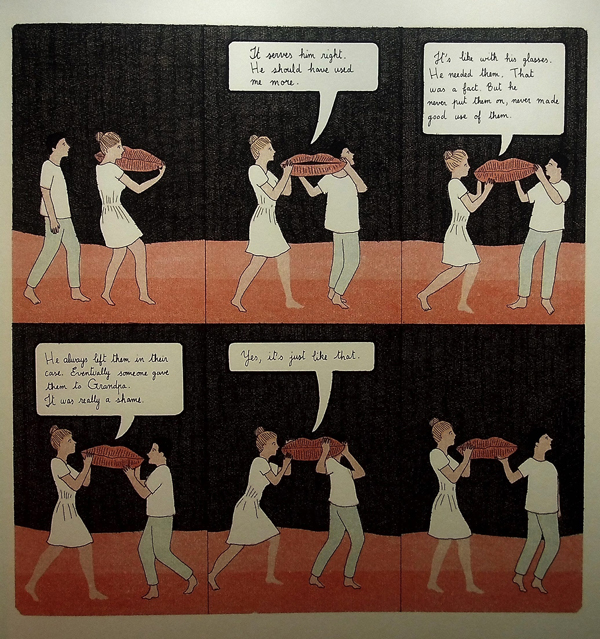

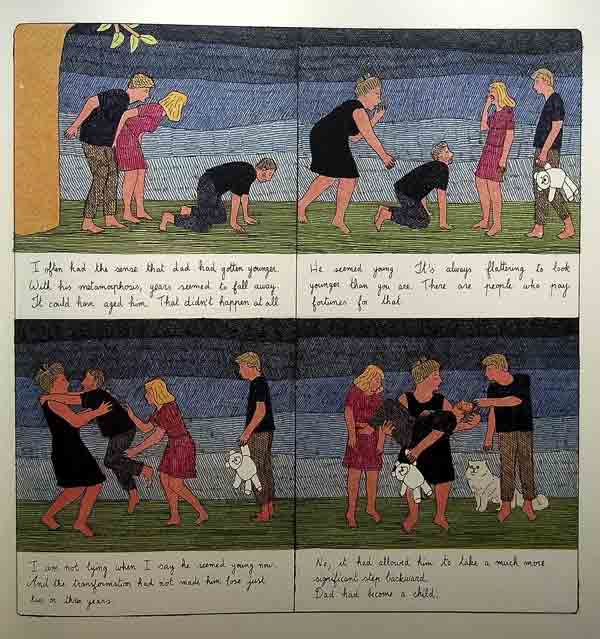

The funeral of the lung turns out to be a practical joke of sorts, a way for the father to gauge how much he will be missed when he passes on. The story continues on in depicting his home care, and though we are supposed to have sympathy for the dying, the father in this story is depicted as a manipulator, disposing of other body parts and taking on regressive personalities in order to torture his family, who wait on him hand and foot.

This doesn’t unfold in a clear way, however. It’s more like a fairy tale of warped perception as the father exists partially as a giant head without features, and then at other times as a regular-looking human being with features intact. That signifies a shift in perception, typically from that of his daughter, the narrator who paints him as a mini Hitler and then perhaps a perspective of more clarity that reveals how things really look without the daughter’s emotional baggage and resentment.

And it does seem like resentment, particularly when portraying his home care professionals as hostile soldiers in white who alternately remove the father’s body parts and then wait on him hand and foot, causing family members to feel like prisoners in their own home. Though it’s spelled out pretty literally at certain points, even in surrealist fairy tale mode, it’s not hard to see this is a relationship of complexity and hostility.

At one point Fayolle writes, “If I’d had to find a substance to symbolize my father, I would have chosen stones. Not, to be clear, gentle pebbles. No, more the boulders that jab your feet if you walk on them without shoes. The kind that are jagged all over. The kind that scratch, that cut, that are aggressive and cold. My father was a boulder that I longed to cling to without being wounded. That I longed to shelter beneath without feeling threatened.”

Those words are accompanied by a flat rendering of a giant boulder that is shaped like the father’s head, resting on smaller rocks next to the seaside and mostly a silhouette, but still reminiscent of the giant head seen earlier in the book that needed nose and mouth removed. The oceans become stormy, bashing away at the rock head and doing what oceans have done to rocks for millions of years, eroding it away into something smoother. In the narrator’s mind, the destructive ocean is a symbol for the disease and the hope is that both should pummel her father’s rough edges into something easier to interact with.

Fayolle’s artwork exhibits a flatness throughout that’s often akin to Martin and Alice Provensen, with a dash of Fletcher Hanks when the imagery gets particularly weird, but in the end it’s all the straightforward body language of loss until the final moment of dissipation for the dad. That’s a moment that’s been inevitable since the beginning of the book but is treated as some surprise when raised as a certainty somewhere near the end. Even as his decline becomes wrapped up in the creative efforts of the narrator and the two become indistinguishable to her, the end is not as expected as it should be, as if the endless process she has been through creates an eternal present during which no end can be conceived.

The Tenderness of Stones is a book about loss, yes, but also the process of getting to the moment of loss, of feeling the loss constantly before the passing, and of grappling with the loss weighed against complex and sometimes troubled relationships. Fayolle puts it all into symbolic terms that allows the absurd to overtake details that would otherwise be unbearable, but she still accomplishes the goal of depicting the seemingly endless grief that accompanies such an experience, whether it involves giant heads with missing noses or not.