It’s 84 pages in before the subject of French graphic novelist Chaboute‘s largely silent work Alone finally appears, and even then, it’s only in the form of a hand dropping food to a goldfish in a bowl. It’s a metaphor for how the deformed Alone — that’s what he’s called — lives his life, isolated in a lighthouse with weekly provisions dropped off by a local sailor. The lighthouse is the fishbowl and Alone is just a goldfish, waiting around for help.

Once he does appear fully, nearly 20 pages later, Alone is picking up his package, freshly dropped off, after quickly hiding at the sight of the boat coming. He is interrupted fishing — that is, taking care of himself — and his flight to a hiding place shows that he is not quite a goldfish after all. He sees what goes on beyond the bowl, reacts to it, fears it. Inside the safety of the lighthouse, he hovers over entries in a tattered old dictionary that elicit memories and fantasies, and sometimes brings the together in order to pass the time.

It turns out that he’s not quite as alone as we thought. In a short sequence that shows the goldfish isn’t as much a prisoner of its own limited perceptions either, Alone and the fish have direct interaction, with Alone taking steps to obstruct the fish from something that causes him despair — the sight of his fish dinner. And then it’s back to the dictionary-driven fantasies.

But if the goldfish can interact with its guardian, the implication is that Alone can also connect with his own. And that connection begins one delivery with an attached note that asks, simply, “Is there anything special you would like?”

The outside world is not necessarily one that Alone equates with comfort and happiness. Besides the boat that makes the delivery, what he knows of it are the seagulls who swirl around the lighthouse and the violent beating of the waves against it. The outside world is not really inviting at all. But even the most dangerous vistas will inspire curiosity, even the desire to explore, and what Alone wants most, what he uses his dictionary for and finds other opportunities to engage with, is to visualize what lies beyond the violent waves. Where do the seagulls come from?

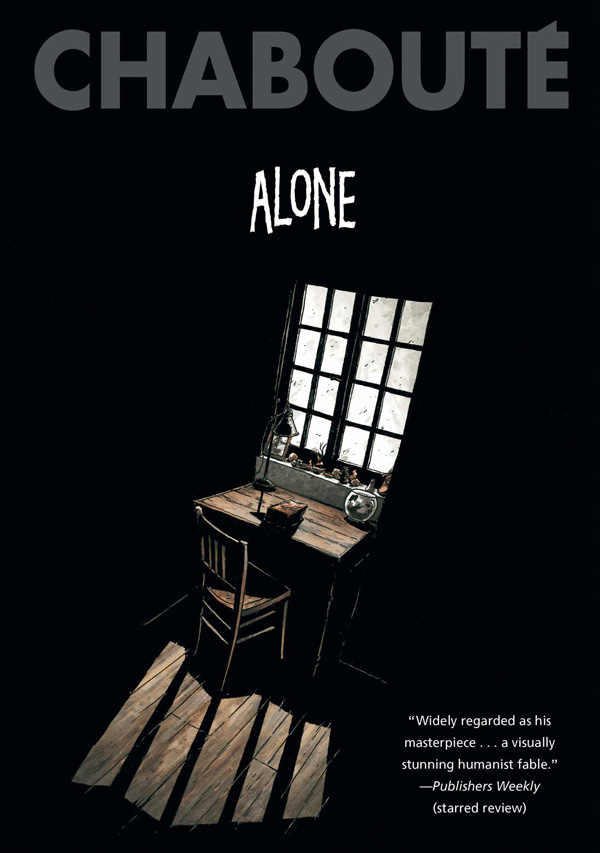

Chaboute captures this life with a slow and mostly silent precision, covering the routines inherent in isolation and the limitless possibilities that can be brought to such an existence, like discovering a whole new dimension. The story is a delicate fairy tale in which the monster is victim, the prisoner of the tower, and in which the isolation that defines his life is revealed as more of a universal existence than even he imagines. As Chaboute offers small slices of the world, he shows that despite our knowledge of everything that goes on around us, we all have our own lighthouse we’re peering out from at the lives of others.

Despite the somber quality of the book, it’s an extremely hopeful one. Chaboute isn’t so airy fairy that he seems to think everything works out happily ever after, but he does imply that it’s the exercise of your freedom to live, the earnest attempt to try and live happily ever after, is the thing that actually matters. Since we’re all in the same situation and struggling to be in the world, it’s those who make an attempt who are the true heroes of our fairy tale.