Underneath the surreal nightmare presented by Swedish cartoonist Max Andersson and despite the dream logic to so much of the action in The Excavation, there’s a truthful core that many of us can take to heart. This is essentially the story of a guy bringing his girlfriend to meet his estranged family for an uncomfortable visit that puts ugly truths about the family dynamic on display. Guy flees, but this has rekindled the familial connection and that means family oversteps boundaries and enters guy’s world unexpectedly, putting guy in an awkward situation with his father, and leaving his girlfriend to deal with the tattered detritus of the other aspects of the relationship.

Typical dysfunctional family story, really, but Andersson presents it in such a way that psychological terror anyone in the middle of it feels — the stuff that’s harder to express, the stuff that sometimes makes you look a bit unreasonable, even selfish, to people who can quite understand the situation — becomes the very atmosphere that the story takes place in.

As the story careens out of control, the guy has to deal with rediscovering his family home, filled with hidden rooms he had forgotten, some impossible to access thanks to the lack of doorways, while there are doorways to other places that are inconvenient, awkward, and never used. This is the guy traversing not only his own family dynamics, but his perception of them as well. If you’ve ever had a dream about discovering an unknown section of your house, or an unknown part of your town, or even visiting a new city that you never knew existed before, then you get the general tone of this storyline. It’s a dreamlike depiction of discovery that part blind, part familiar, and filled with spontaneity that challenges your decisions.

Meanwhile girlfriend is plunged into her own version of a similar world — distress in the streets of her home and hidden corners of danger that the guy’s family force her to plunge into, going so far as to be stripped of her own persona and forced to put on another woman’s wig and dress as she traverses the strangeness.

If you’ve ever married into a dysfunctional family, this part will make you nod your head as you read. Even coming from your own version doesn’t help — each family’s dysfunction is a personal language that does not translate to the situation of others, and you can find yourself in a situation that’s not unlike being an English-speaker dropped in the middle of China and being told to just figure it out.

Once the couple is reunited, they are faced with coming to terms with the bile dredged up by their adventure, as they relate to each other with altered appearances brought on by the trauma of dealing with the family. But by then, calamity has entered their lives like an atmosphere to exist in and the ultimate solution of escape is probably a universal one that many of us have sought out on our own terms.

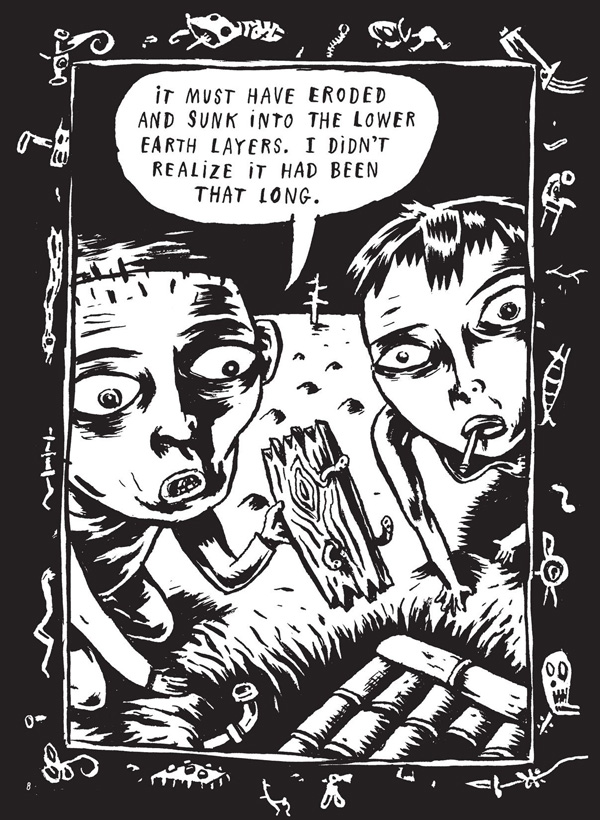

Andersson’s art work has a Gary Panter-like feel, but as if the Eraserhead baby dreamt in Panter’s style. This of course puts the surrealism on turbo, but also the ugliness. It’s not a grim world that Andersson presents, but it is a decrepit, dark one that accesses the more prurient parts of the soul, where reality is Times Square of old, and any water you use to wash it off is filled with muck and shit and germs. And yet it’s a funny one too — as despairing as it gets, Andersson always injects slapstick and cleverly amusing dialogue that reveals it as far more than just an exercise in negativity.