I have loved Julie Delporte’s work since I first read her 2014 book from Koyama Press, Journal. I’m going to tell a dumb story now. Well, an okay story where I say a dumb thing. Shortly after I read it and reviewed it, literally within the month, I was in Librairie Drawn and Quarterly in Montreal for an event there when I was introduced to Deporte, who worked there.

“You’re Julie Delporte?” I asked, like I couldn’t believe it was true. I mean, I had JUST read the book.

“Yes,” she smiled.

“I just read Journal and reviewed it and loved it,” I told her. And then I said the dumb thing. “I hope you’re doing okay. Are you okay?”

She just laughed and said that she was. And I immediately thought, STUPID STUPID STUPID at myself. But that’s how affecting Journal was. That’s how much it drew you into her interior and created a bond between herself and the reader, and how skilled she was at interpreting her own inner experience into comics form. It hit me so hard that upon unexpectedly meeting her so close to when I had read the book, I just wanted to know if she was okay. As sublime as her presentation was, it felt horrible to know this person bursting with creativity was having such a hard time.

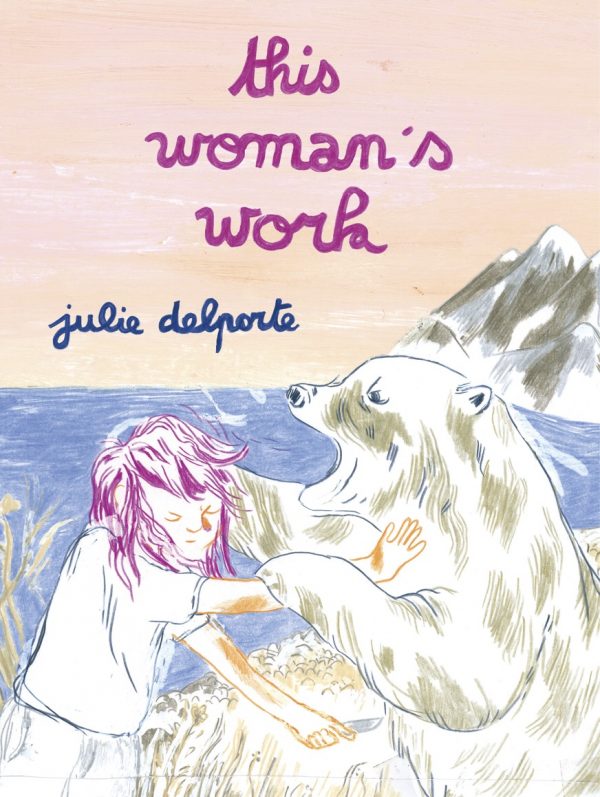

It’s about five years later and holding Delporte’s upcoming This Woman’s Work in my hands, I see that none of the intensity has left, nor the brevity she injects into the intensity, nor has any of the immersive emotions that she lays out there. Her work is still raw, and she is still impeccable at laying out an unmappable thought process that feels like a profound journey into the unknown, where she creates bridges connecting the intensely personal with the completely universal, where cultural elements and her own obsessions and landscapes and the lives of others collide into a psychological landscape all its own that may be hard to parse out the individual aspects, but leaves you feeling the enormity of what she’s put down on paper

Deporte’s book borrows its title from the Kate Bush song about childbirth, which itself takes its title from the notion of childbirth being something that women do by themselves and men neither need nor want any part of it. In some ways, it’s one of those “putting women up on a pedestal to limit them” kinds of phrases. It also exoticizes something that is just part of the normal human experience, childbirth. The cartoonist relates this concept to her father’s proclamation of something done poorly being “a woman’s handiwork” thus examining her own place in the circumstance, in regard to a wider, more accepted cultural depreciation of women and their contribution.

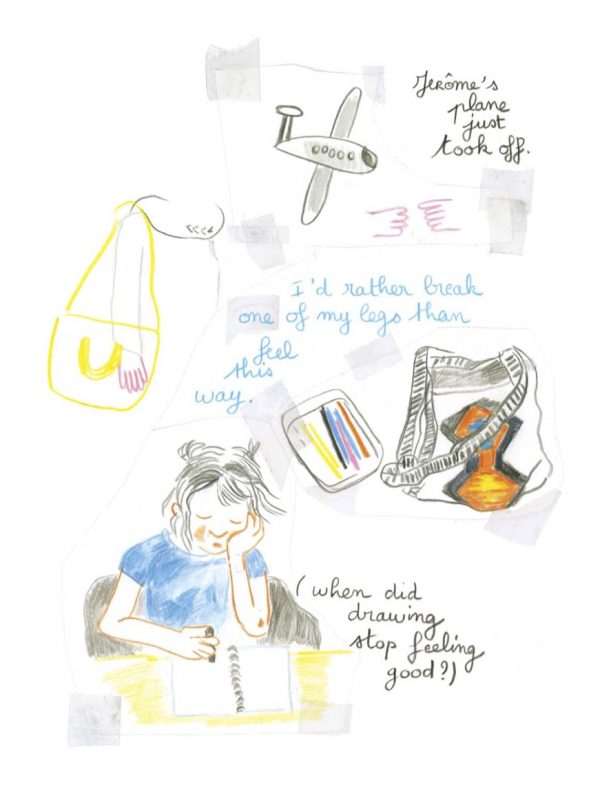

With this as her springboard, Delporte’s concerns cascade, from the male dominance of her native French language to the place of men in family and parentage, to the dynamics between women and the men they fall in love with, the role of women in art, the practicalities of women creating art in a patriarchal system, and how all that smashes between culture and personal lives, and, of course, what all that means in regard to her own experience, which evokes dream diaries and some traumatic personal recollections.

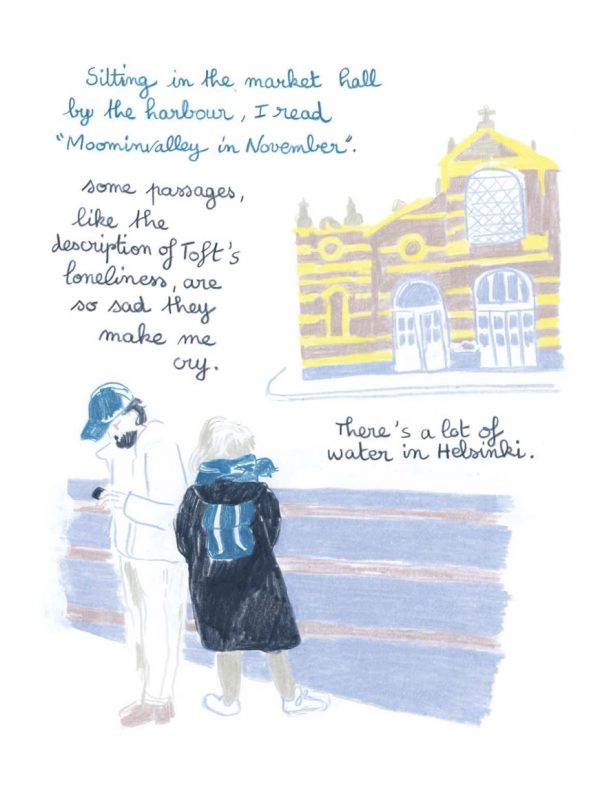

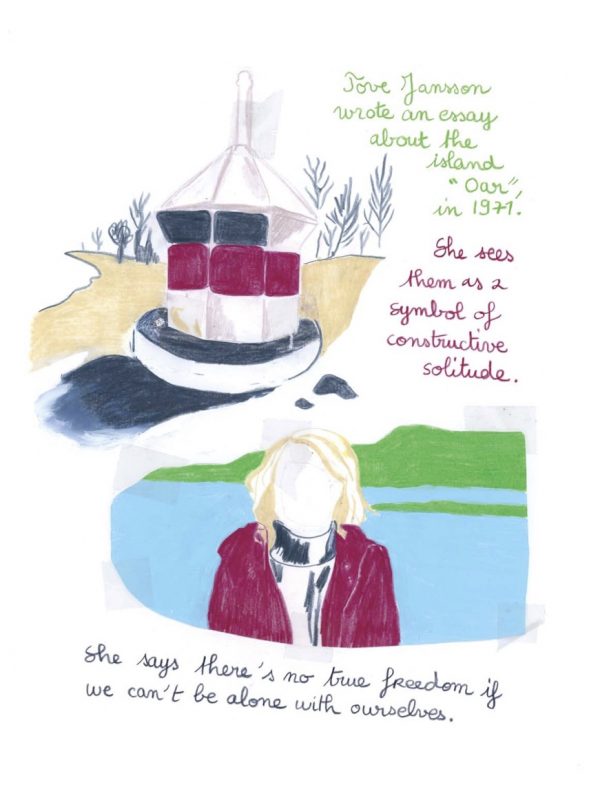

It also wraps around women of inspiration, most notably Moomins creator Tove Jansson, who is the impetus for a trip to Finland that Delporte documents in the book and who winds through the book like a guiding spirit. Part of that has to do with Jansson’s life, which she lived as a person who knew herself and is truly inspirational because of this, but also for her creation of the Moomins, simple creatures who inspire more complicated admiration by those of us who feel a kinship. Delporte often measures her own experience against other women in creative fields, historical and contemporary, with the idea that seizing the time to devote to their creative calling is a tougher battle for them than it is for men, that it’s something women have had to argue for rather than just slip into effortlessly.

By doing this measurement, Delporte is calculating what effort is required of her to achieve what is desired in her creative life. It’s a different thought process than a man might have to go through, one that instead of just taking into consideration the obstructive circumstances of your personal situation, also must consider ingrained attitudes of thousands of years of human culture that have been piled on as barriers to women living lives built from their own decisions.

But I wouldn’t say that her presentation of this process is linear, and that, to me at least, makes it more exciting. This is not a manifesto, at least not as we typically know them, but a poem that explores the ideas that might end up in a manifesto or might not. It’s the poetry of figuring things out. A manifesto is a final decision, but I’m not quite sure if final decisions actually exist, or just seem to in the moment. Understanding is a constantly changing state of mind. Age and experience continually change the ideas you’ve previously thought. Manifestos are probably illusions.

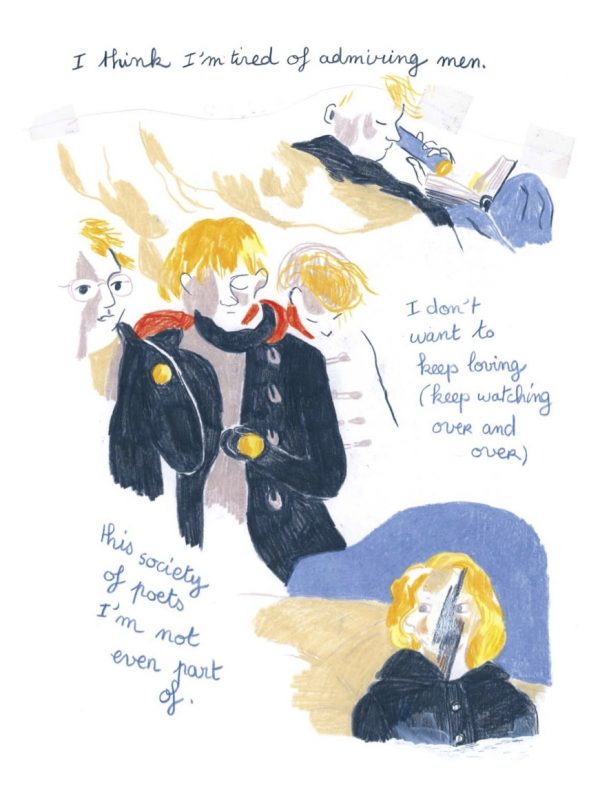

Delporte’s artwork always matches the poetry of her words. Snippets of images that are sometimes more simple bursts of color, other times more complex representations of what she’s speaking of, they often provide a joyous counterpoint to the more despairing quality of her words and themes, not to block those out but to join them and represent the whole person. The artwork also drives home the intensity. Much as Delporte’s words are those of someone who thinks and feels big, so is her artwork that of someone who sees the world through a deep perception of color and form and texture.

As a man reading Delporte’s work, I am always enlightened, always touched, and also always embracing the parts that I can identify with. I think that’s a good thing for men to do, and something they don’t do often enough. Acknowledge the parts you don’t already know and think about them. But then also see commonalities that can help you put yourself in the circumstances she speaks about and, through her, many women express. You’re not going to find a more sublime, more perceptive, or more honest guide to those ideas in comics form than Delporte.

And for the record, as I finished This Woman’s Work, I found myself once again concerned that Delporte is okay. But that’s just a measure of the work’s success, that the ideas expressed are manifest as a living, breathing person that you care about. I think that’s probably how change happens.