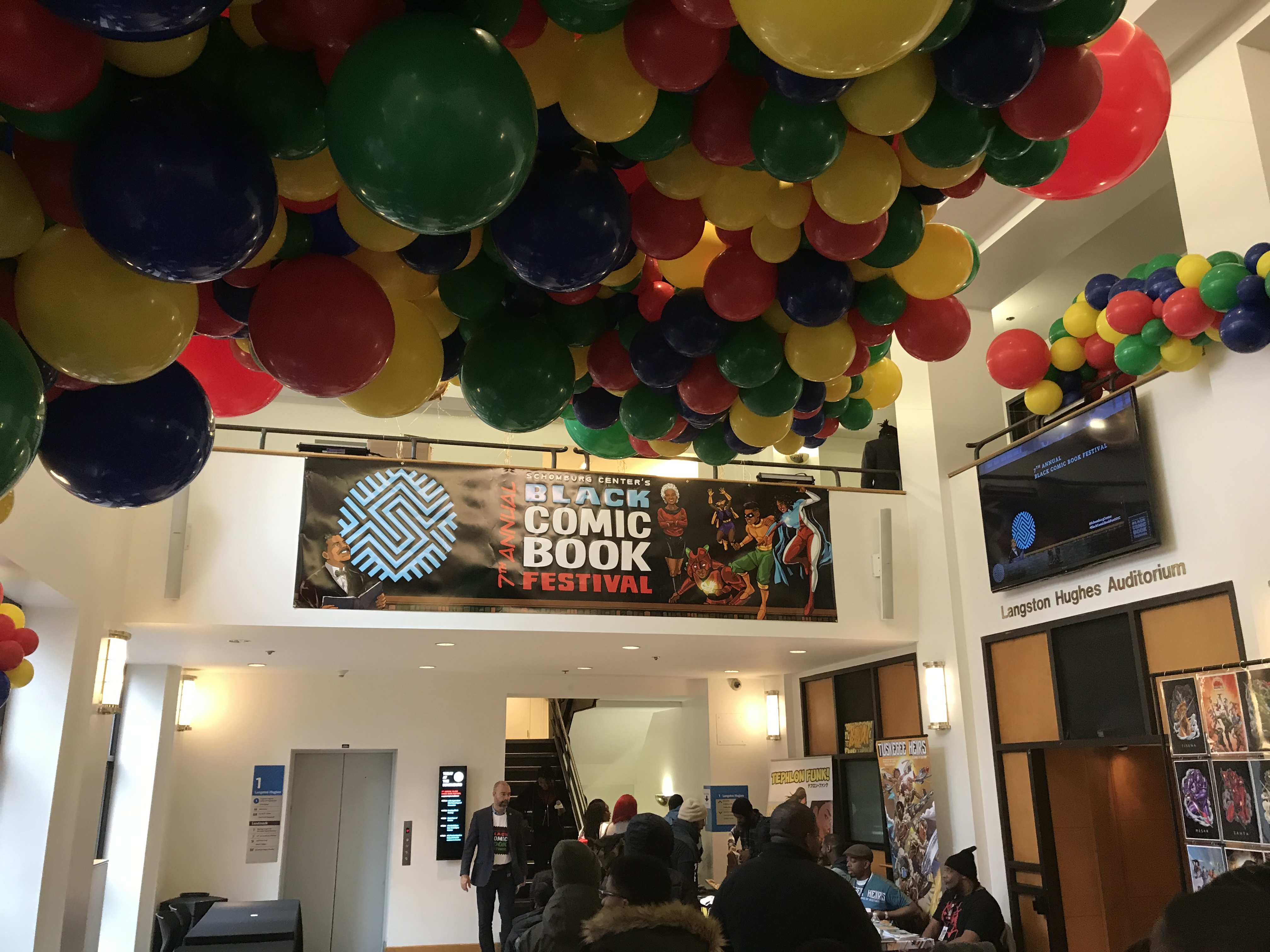

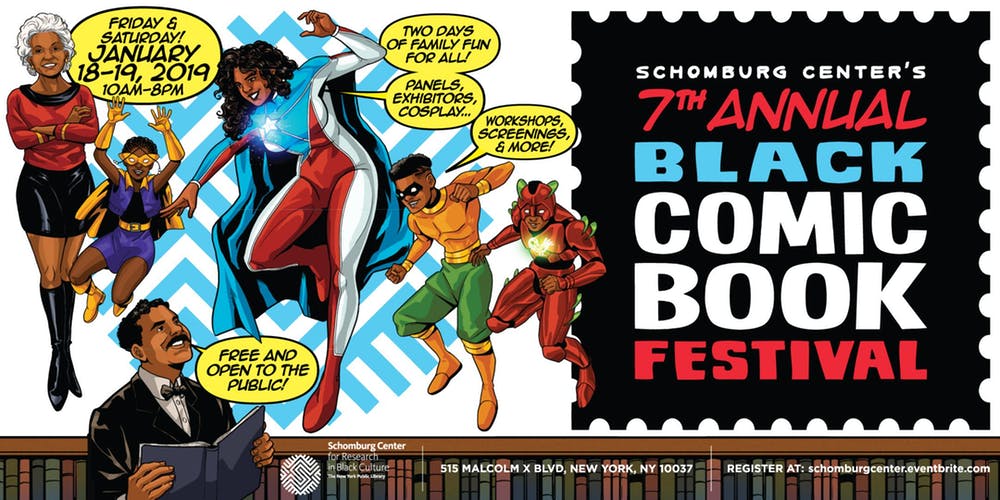

The 7th annual Black Comic Book Festival, which took place on January 18-19 at the Schomburg Center in Harlem, was a fierce statement on black representation in comics. Not a plea but an actual boots-on-the-ground, grassroots expression of black creativity, independence, and resiliency.

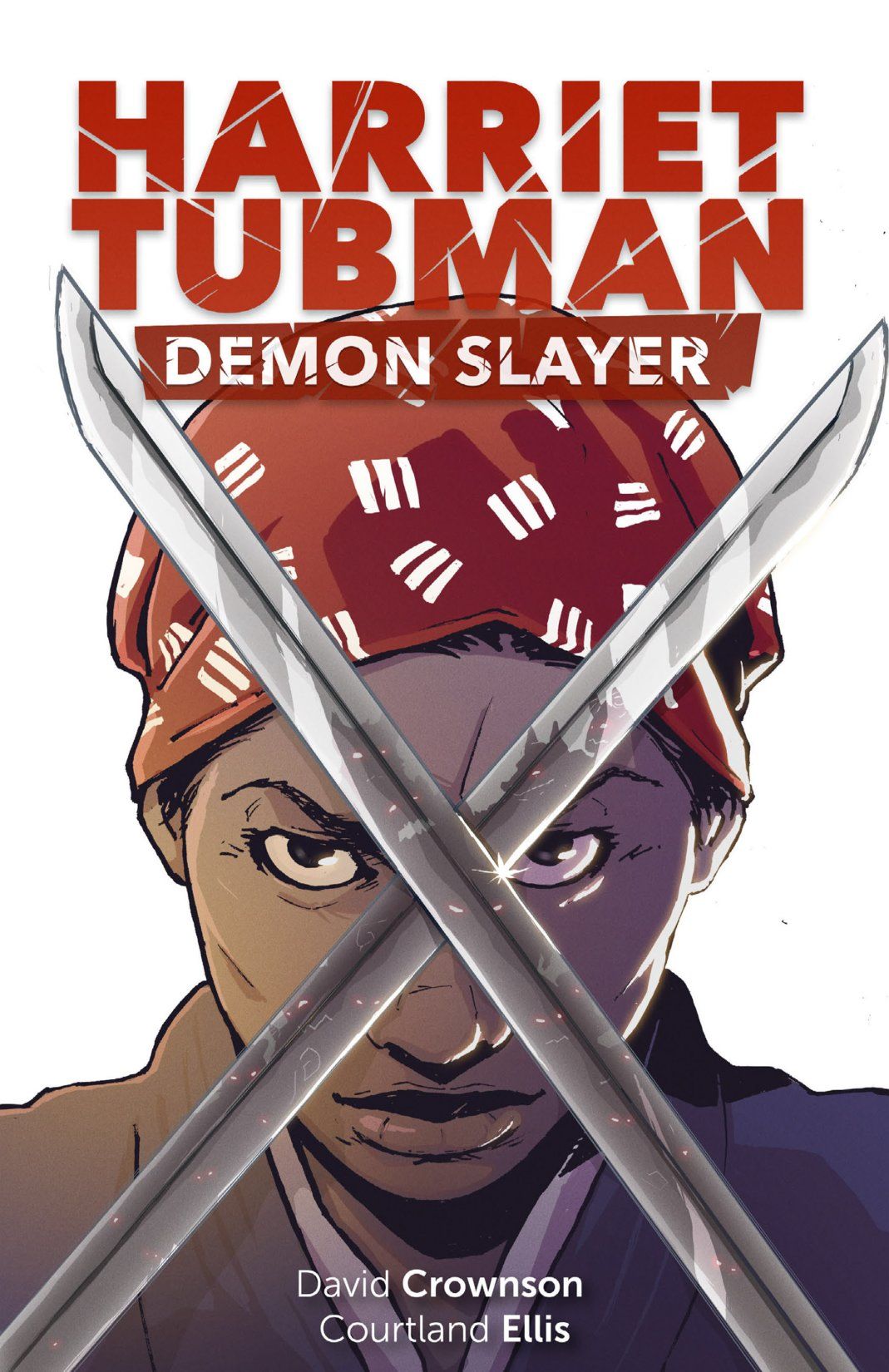

Those who think comics are running out of ideas need to keep the Black Comic Book Fest on their radars. The black superhero stories presented at the festival weren’t just black versions of Batman or Wolverine or the Justice League. They are fresh creations that carry with them unique particularities rooted in the black experience. They carry a history that diverts into less explored forms of comic book storytelling. That is, unless you’ve heard about a demon-hunting Harriet Tubman before. Or about the experiences of a black bouncer from Brooklyn. Perhaps about the heirs of the Tuskegee Airmen?

Having a singular focus on a community’s voice in comics specifically gave the festival a chance to stretch its legs and really let loose with the topics and themes they wanted to explore. This was the case with the ‘Black Villains Matter’ panel, hosted by Michael Flood, in conversation with Kennedy Allen (Black Tribbles podcast), Janicia Francis (Tea with Queens & J. podcast), Royce Johnson (Netlfix’s Daredevil and The Punisher), and Ronald Simmons (You Don’t Read Comics).

Of special note was a conversation on Killmonger. The Black Panther villain was discussed as a character that wanted to take over the same system of oppression that preyed on his people to use it to his advantage. That he didn’t want to change the system, that he wanted to become the oppressor, might mean Killmonger is being led by the traumatic experience of being a black man in America. He makes it his righteous quest, As Kennedy and Janicia argued.

Black Adam was presented as a kind of question, a challenge even, to comic book readers. His villainy hovers around the idea of whether one must become a villain to achieve genuine justice. And this form of justice, Kennedy reminded the audience, is not universally evil. From a black perspective, this type of villainy could be a reaction to how the justice system treats and has treated people of color. As Kennedy later added, “good doesn’t always cut it.”

The panel also agreed that we should stop using the word ‘Black’ as an adjective for evil characters or characters that aren’t black, like Black Canary or Black Cat. In addition, black heroes don’t always have to adhere to the “angry Black man” trope, nor do they have to be the only good guy in a black neighborhood (cue Luke Cage being “the only good guy in Harlem”).

These types of discussions extended to the show floor and the comic creator booths. There’s a charm to smaller comic conventions and festivals. People have more opportunities to talk comics with writers and illustrators in a space where you’re not competing with state-of-the-art sound systems designed to be heard all over a giant convention center. While the Schomburg does struggle with physical space (mobility is a challenge given how much the event has grown over the years), the place really does thrive when multiple conversations are happening at once. It all comes alive in a way few conventions do.

Bounce!, by Chuck Collins, returns to the Black Comic Book Festival with its most recent publication, offering yet another look at how black comics flip narrative formulas on their heads. The comic is based on Collins’ own experience as a bouncer in NYC and how he dealt with sexist jerks, racist club-goers, everyday drunks, and most if not all forms of stupidity. For those who had not been exposed to this gem of a comic book beforehand, BCBF had you covered.

The cosplay showcase was another highlight, presented by Kanene Holder and Aixa Kendrick (Black Issues Issues). Holder and Kendrick interviewed each cosplayer and developed a funny, political, and highly entertaining performance that turned the showcase into an improv session honoring cosplayers and the characters they brought to life. It was yet another celebration of black representation as characters such as Blade, Prince Akeem from Coming to America, Black Manta, Black Panther, Moon Girl, and Agent J from Men in Black were in attendance along with Harley Quinn, Mera, and a gender-bending Spider-Man 2099. It a was a friendly but firm reminder that comics are for everyone.

The festival closed with a panel on black women writing comics titled ‘Scripting our Stories’, a conversation with Jamila Rowser (Wash Day), Shawnee and Shawnelle Gibbs (The Invention of E.J. Whitaker), Regine Sawyer (Women in Comics, Lockett Down Productions) and Vita Ayala (The Wilds, Livewire), moderated by Karama Horne (theblerdgurl.com).

Each panelist spoke with a sense of power about the work they’ve put into organizing themselves and offering support while simultaneously becoming an even stronger force to be reckoned with. They showed just how strong the community is and how they are succeeding in breaking antiquated rules and creating new ones.

That, in itself, describes the Black Comic Book Festival. It’s a creative space that follows no one else’s rules but its own to focus on showing just how much good can come from change. This is definitely one of my favorite comic events. I recommend everyone keep their eyes on it as the festival continues to grow, something it’s been consistently succeeding at for seven years now. This was only my second year attending the event, and I’m already planning on coming back next year. It’s as unique and genuine as comics events get, and you just can’t shake the feeling you’re part of something important while there.

Photography by George Carmona III.

“The panel also agreed that we should stop using the word ‘Black’ as an adjective for evil characters or characters that aren’t black, like Black Canary or Black Cat.”

Well, apparently insanity was on panel as well… I’ll be careful tonight if I go out walking and slip on some black ice…. Whoops! Can’t say that anymore either now…

So Scarlett Johansson’s upcoming movie will have to be called “White Widow”?

Comments are closed.