In my experience, once people get older and their teenage experience settles into a hazy myth in their brains that supplants the actual memories, almost everyone thinks they were the weird-one-out in high school. Even the most privileged types see themselves in outcast terms. I don’t know that this is human-nature, but it is American nature, and it’s one of the difficulties in selling the concept of privilege to those who actually have it.

But it’s also an indicator at how we look at people these days, that the concept of privilege sometimes supplants the devastation of personal trauma in a someone’s life, at least in regard to how they appear from the outside and how their own hurt is qualified by others.

I don’t actually think we need to compete in the areas of hurt, trauma, alienation, or harassment, but rather to accept that most people encounter these in some way and the commonality of hurt should unite us in helping each other rather than having us compete for who’s got it worse.

But the way things are now, often the people who really do have it worse, whose outer situation matches their inner turmoil and creates inescapable instances of oppression, are put in the position of having to find that commonality to state their own case and create their own defense. Some in this position are understandably sick of it. Some aren’t very good at it anyhow.

And then there’s L. Nichols.

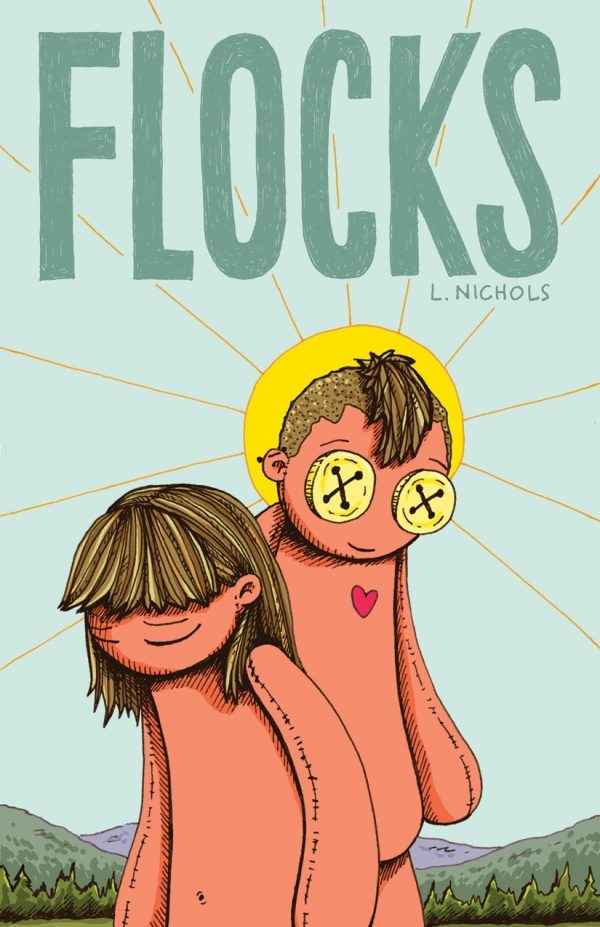

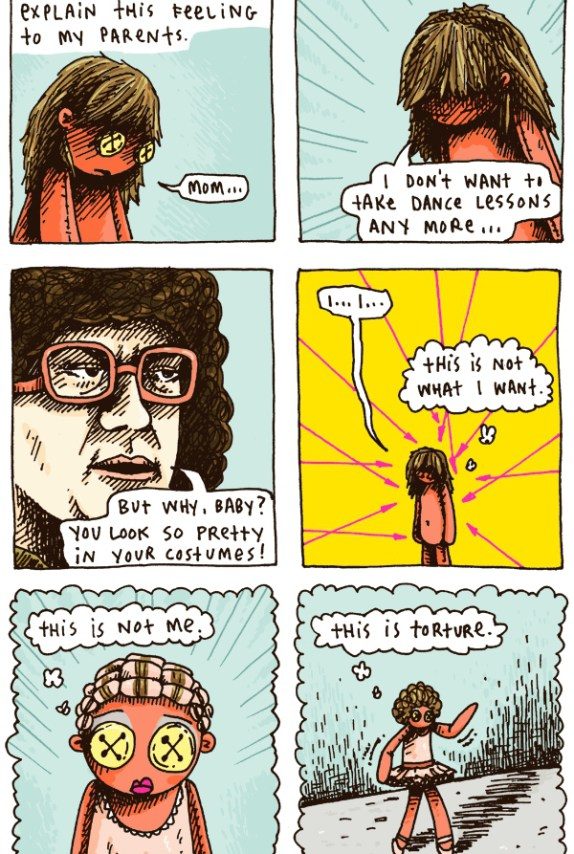

In Flocks Nichols recounts his earlier life as a gay girl and woman, and then transitioning in his 20s. Nichols possesses an uncanny ability to express personal traumas and discrimination in various situations and use this mix to express a universal property to the struggle. The focus of the book is the self-hate that consumed him due to the outward hostility toward her sexuality by the tribe he was born into — church-going Christians — but as he relates this autobiography, he also mentions some other circumstances where he encountered hostility, in the area of weight and region-based speech pattern.

As Nichols points out, these are areas that someone might be able to control or change more than sexuality, but they are also places that offer other people the chance to find commonality Nichols’ story with even if their understanding of hate because of sexual orientation is abstract. The world that Nichols portrays is one that goes out of its way to dissect a person and find a reason to make them feel separated from the norm. It’s a dynamic many people experience. It’s what makes us human.

Of course, what Nichols portrays is an institutionalized hate, that of fundamentalist Christianity toward the gay community, and its manifestation in the real world and through history is a deadly one compared other judgments that people face. The force and ferocity with which some sects express this hate inspires many victims to hide among their oppressors because they have no other choice, and to do the work of their oppressors by punishing themselves into agony and often physical pain. They hide to escape danger, but what happens in private and in their minds more than makes up for it.

Nichols doesn’t downplay the level of hurt and horror this creates, but he doesn’t let that taint his narrative either. Despite what the books portrays, this is a very uplifting work that strives for togetherness more than expressing rage or seeking revenge against those who wronged her. It’s very much an examination of group dynamics and how they can work against individuals, but also how that shouldn’t stop you from remaining open to a like-minded group as you walk through your life. It’s not only about acceptance, but about refusing to allow those who hate you to taint your own practice of acceptance and obstruct your own quest for it.

The way Nichols does this is by acknowledging the strengths of his life as well as the weaknesses. That’s a hard thing to do, actually, because the allure of making yourself a total victim is sublime, it can create warmth and connection in its own way, and it’s the embrace of that dynamic that can perpetuate the victimhood and disarm the strengths within you. But your strengths are what you have to work with, and Nichols recognizes this even when he seems oblivious to it. He takes stock of what is right in her life and analyzes how these can change what is wrong.

He also refuses to demonize his oppressors, but instead treats them as human, albeit humans who are enacting a form of hate that is wrong. By taking this view, he is also able to express how his oppressors were part of the mixture that made him who he is, and how he refuses to let them taint what he likes about his upbringing and about his faith.

Nichols portrays himself visually as a rag doll, but he is the exact opposite of that — he’s a pretty solid example of what can be achieved if you persevere.

Comments are closed.