Towards the end of his life, witnessing the rise of the graphic novel as a format, Will Eisner commented on the fact that his books formed a subsection of the graphic novels display at a large bookstore by clarifying that his desire was to see his books shelved in the literature section alongside works by Jewish-American novelists of his generation (as expressed in an interview with David Hajdu). It’s enough to make you chuckle that he wasn’t pleased enough with the impact his books had on pushing the graphic novel format forward in American comics, but at the New York Comic and Picture-Story Symposium on the 11th of March, an Eisner-Week event critiqued the comparison between Eisner and his generation of fellow writers to see if his work stood up to his own claim of similarity. Speakers Jeremy Dauber (Professor in Yiddish Studies at Columbia University) and Danny Fingeroth (educator, author, former Marvel Comics editor and Chair of the Organizing Committee for Will Eisner Week) investigated Eisner’s use of setting, dialogue, and themes, as well as common cultural references he shared with his generation, to place Eisner in context and challenge the divide typically assumed between prose and comics media.

[Dauber and Fingeroth]

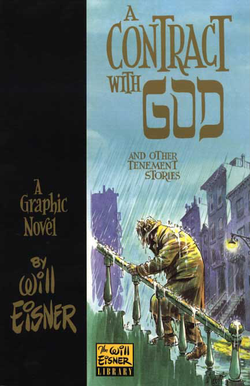

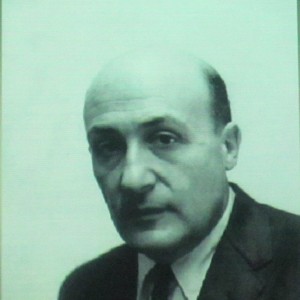

Dauber pointed out, in opening, that Will Eisner’s work is not usually considered in comparison to novels. He’s known for his prose, and often narrative-heavy work, but close textual comparisons between his writing style and those of his contemporary prose-writers is sparse, or even non-existent. Born in 1917, and “coming of age” in the 20’s and 30’s, Eisner, Dauber said, “was present a the foundational moment of Modern American Jewish Literature” and surrounded by the same influences and trends of major novelists of the period. Abraham Cahan, for instance, who fled from Czarist Russia to become a longtime editor of Yiddish newspapers in New York, was a “break through writer” in establishing Jewish-American literature. He often described the “urban landscape” as “something that’s alive”, as artist Andrea Tsurumi observed during audience participation. In comparison, Eisner’s CONTRACT WITH GOD gives a strong sense of place, and often speaks in a “high register” of prose, like Cahan’s work.

[Jeremy Dauber]

Another prose writer who became a “household name” during Eisner’s childhood was Anzia Yezierska, the “Cinderella of the tenements”, who often found herself in conflict with her parent’s generation, forged her high school diploma in order to attend college, and found herself exploring the conflict between the old and new world in her prose. Her use of dialogue, contrasting idiomatic Yiddish-English with her own more formal style of English speaks to a tension also visible in Eisner’s dialogue. Dauber presented novelist Henry Roth’s work as a final comparison in the use of dialogue to show differences in cultural background also found in Eisner’s Dropsie Avenue inhabitants. Dauber also pointed out a similar fascination with religious experience as a “transforming” force between Roth and Eisner.

[Danny Fingeroth]

While Dauber explored prose comparisons between Eisner’s work and other Jewish-American novelists, Fingeroth took a more visual approach to putting Eisner in context. He addressed the fact that many of the novels of Eisner’s generation and milieu found their way into film adaptation, like Philip Roth’s GOODBYE COLUMBUS (1969). This forms a visual link to Eisner’s own graphic novels and work as an artist. Like Saul Bellow, Eisner also embraced a strong sense of comedy in his work, whereas authors like Bellow didn’t seem to acknowledge comics as an expression of their generation. In a video clip Fingeroth played for the audience, Eisner described himself as “growing up in an environment of prejudice and exploration of identity”, a theme certainly visible in many of the Jewish-American novels of the period. Eisner’s injected his characteristic humor by adding that writing was “inexpensive long term therapy” for these issues.

[Will Eisner]

Fingeroth described the “Jewish-American assimilation experience” as a common feature of Eisner’s work and his novelist contemporaries. CONTRACT WITH GOD, the “first thing” Eisner created in his long career that “wasn’t an actual assignment” allowed him the freedom to revisit these very personal experiences. Fingeroth also noted that a common cultural reference among these writers was Baseball, as seen in Philip Roth’s THE GREAT AMERICAN NOVEL, and in Eisner’s artwork on “The Adventures of Rube Rooky”. Writing about baseball, Fingeroth explained, was a “leveling process” between cultures that became part of the assimilation process. Visually speaking, Fingeroth said, Eisner was a “master of this craft of depicting urban life” found in celebrated Jewish-American novels. Particularly in A CONTRACT WITH GOD, Eisner, “given the freedom to do what he wanted to…came up with stories based on the Bronx of his youth”, like other writers of his generation.

[Saul Bellow]

Fingeroth reminded the audience that exploring Eisner’s prose shouldn’t take away from Eisner’s own assertion that he “wrote with pictures”, though. According to Dauber and Fingeroth’s research, Eisner wrote “as well as anyone” else prominent in his generation. To understand Eisner’s legacy, we have to keep in mind that he “thought of himself as someone who wouldn’t be complete without pictures”, Fingeroth said. So, after this careful textual and cultural comparison between Eisner and the Jewish-American novelists of his day, what was the verdict? Could Eisner’s works be placed in the “literature” section of a bookstore next to the novels he felt expressed the same messages? “Will made it”, Fingeroth confirmed, “He belongs there, too”.

During the question and answer period, discussion turned toward Eisner’s overwhelming drive to raise awareness of comics as a medium. Fingeroth described Eisner as being on a “mission to explain his own life and to legitimize comics”. It’s a puzzling thing that Eisner apparently wanted graphic novels to be seen as “mainstream” literature rather than as a separate format, but the answer may lie in his sense that graphic novels were still being segregated from literature and therefore not treated as equal creative achievements. The double presentation of Eisner’s work in context from Dauber and Fingeroth made a strong argument for Eisner’s status alongside novelists of his day, especially in terms of subject matter and prose style. Dauber and Fingeroth presented reasonable evidence that Eisner’s work could be reshelved in the literature section at any bookstore, but it might cause quite a tug of war with those who see his work of “legitimizing” comics as most at home in a separate graphic novels section of books. “Ideally, all sorts of books could be shelved in more than one section of a bookstore or library,” Fingeroth added in a follow-up comment, “but a variety of practical reasons make that unlikely for the time being. Online venues seem to be able to do it, though, so hopefully some version of that will come to brick-and-mortar outlets, too.” So, why not place Eisner’s books in both locations? It might remind readers, for one thing, to view Eisner as a cultural peer of many of the novelists he revered.

Hannah Means-Shannon writes and blogs about comics for TRIP CITY and Sequart.org and is currently working on books about Neil Gaiman and Alan Moore for Sequart. She is @hannahmenzies on Twitter and hannahmenziesblog on WordPress.

I like Eisner’s later works for a variety of reasons, but I would never compare them with a good novel. The complexity of character and plot just isn’t there. Neither is the structure needed for longer works.

“Ideally, all sorts of books could be shelved in more than one section of a bookstore or library,” Fingeroth added in a follow-up comment, “but a variety of practical reasons make that unlikely for the time being. Online venues seem to be able to do it, though, so hopefully some version of that will come to brick-and-mortar outlets, too.”

What drives me crazy about these types of statements is that people need to understand how the structure of a library or brick and mortar store works as opposed to an online retailer. First of all, the buyer/librarian purchasing graphic novels is most likely not the same one buying fiction/literature. So, if you theoretically have the book in two sections of the store, you would then need to buyers tending to that title – monitoring sales, keeping inventory levels, etc. That is not a very efficient way for a company to run their business. Having them in more than one section also adds to the amount of inventory a store, or how many copies a library needs to buy for that title. More money tied up in inventory is not a good idea. This is particularly true of libraries who buy books on a non-returnable basis and have their budgets stretched as it is without having to buy two copies just to shelve them in two different sections. They would need to sacrifice buying another book, just to be able to buy two copies of the same book.

So, why are online retailers able to cross promote in different categories? It’s because the inventory for an online retailer, for that book, is on a shelf somewhere in a warehouse. The warehouse acts as a common feeder no matter if you buy it under the guise of a graphic novel, novel, art book or household appliance.

While these discussions may be interesting from an intellectual point of view an understanding of how the system works is not a bad idea. That way

My comment got cut off – to finish.

That way more practical and workable ideas on how to promote the medium could be discussed.

Rich, please note that I said, “…but a variety of practical reasons make that unlikely for the time being.” You have listed that variety of reasons. My statement doesn’t attack brick-and-mortar retailers. Just the opposite.

Thanks for posting this. I explored reflections of Jewish American literature in comics as part of my dissertation for my PHD at the University of East Anglia. I found strong expressions of concerns with assimilation in Eisner’s work and in novels by Jewish American writers, including Henry Roth, Anzia Yezierska, Abraham Cahan, and Philip Roth. Many of Eisner’s stories remind me of the fiction of Delmore Schwartz, Cynthia Ozick, and Issac Bashevis Singer. There are echos of the urban settings, immigrant neighborhoods, and memories of Eastern Europe. It’s interesting that many of Eisner’s later works are responses to novels Fagin the Jew — or examinations of prose, such as The Plot: The Secret Story of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion.

Danny

No I saw the comment you refer to and wondered what “practical for the time being” could mean. When would the structure of retail business in bookstores change so much that they could support buying double inventory? As for an attack on brick and mortar – I didn’t see it that way. I saw it as a wish on how things should work over how they actually do work.

Ivy- great that you are researching this topic!

Some of the other authors you mentioned came up in the talk. I’m sure if you wanted to get in touch with Jeremy Dauber you’d have lots to talk about.

I believe Will Eisner’s concerns belonged to a different era (or at least –era that has not passed but is well on the way outside). His desire to have his works placed alongside “regular” books was understandable in the context of that time – comics needed all the legitimacy it could get and putting it on same shelf (metaphorically and physically) with novels gave the medium the leg up it needed. But now that [the comics medium] has the legitimacy insisting on keeping the same shelf will only bring it down – ideally, comics should have its own cultural shelf.

It was cute at the time but today it is kind of insulting that Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns are the only two comic-books on the TIME’s 100 best novels list because we infer from that there are only two worthwhile comics in the 20th century. I don’t think Eisner (or Moore, or (early) Miller) are JUST as good as Jay-random-novel-writer… I think They are A LOT better.

@Mark Mayerson: I’m not sure that Jeremy was positing that Eisner was a novelist, exactly. He was looking at the themes taken up by the great American Jewish writers of the early 20th century (Cahan, Roth, Yezierska), such as assimilation, generational conflict, the New York urban landscape, etc, and wondering how much of an influence they might have been on Eisner. And, to illustrate, Jeremy compared passages from works by each of those authors with passages from works by Eisner.

The question was less, perhaps, “Was Eisner a novelist?” than “Where does Eisner fit in the tradition of the American Jewish voice in literature?”

With the main question “Was Eisner a novelist?” I would argue that in the context of how he presented the stories, sure. To Karen’s point I think the case could be made that he was also one of the original Jewish voices in literature.

Rich Johnson’s point comes at a moment(yet again) when I’m having conversations with comics publishers about the need for proper cataloging for their graphic novels. In the library(public and educational) as well as with traditional retail there are guidelines for creating catalog information about your book. If you dont have this information created or you do a poorly informed job of it, you minimize the discoverability of the book. For instance, if you do a search on your library’s data base for books containing subject or genre you are less likely to find any comics/graphic novels than you would a list of titles from the traditional houses. This is because most comics pubs have absolutely no idea as to why PCIP (Publisher Cataloging In Processing) is important.

A library’s database is, in a way, their answer to an online retailer’s ability to provide multiple listings for a single title.

Rich made a lot of inroads to the library market when he was at DC and you see that reflected even today as DC continues to have greater sell through to the library channel than other publishers.

Back to the point, I do think Eisner was a novelist who worked with a different set of tools.

Below is the MARC record for Eisner’s DROPSIE AVENUE. The subject headings at the end (650s) seem as appropriate for the book as they would be for a prose novel on the same subjects. The book would probably be shelved in a library’s GN section, rather than in Fiction by Author, but the subjects are easily accessible through a catalog.

LC Control No.: 95013159

LCCN Permalink: http://lccn.loc.gov/95013159

000 01094cam a2200301 a 450

001 2086779

005 20010126170513.0

008 950309s1995 maua 000 0 eng

035 __ |9 (DLC) 95013159

906 __ |a 7 |b cbc |c orignew |d 1 |e ocip |f 19 |g y-gencatlg

955 __ |a pb04 to la00 03-09-95; lk25 03-13-95; lk25 to Subj. 03-13-95; lh06 to Gen. for PN: graphic novel; lg07 to SL 03-21-95; lg11 03-22-95; CIP ver. pv03 09-13-95

010 __ |a 95013159

020 __ |a 0878163492 (hc)

020 __ |a 0878163506 (signed hc)

020 __ |a 0878163484 (softcover)

040 __ |a DLC |c DLC |d DLC

043 __ |a n-us-ny

050 00 |a PN6727.E4 |b D75 1995

082 00 |a 741.5/973 |2 20

100 1_ |a Eisner, Will.

245 10 |a Dropsie Avenue : |b the neighborhood / |c by Will Eisner.

260 __ |a Northampton, Mass. : |b Kitchen Sink Press, |c c1995.

300 __ |a 170 p. : |b ill. ; |c 27 cm.

651 _0 |a New York (N.Y.) |x Fiction.

650 _0 |a City and town life |x Fiction.

650 _0 |a Immigrants |x Fiction.

655 _7 |a Graphic novels. |2 lcsh

991 __ |b c-GenColl |h PN6727.E4 |i D75 1995 |p 00055583602 |t Copy 1 |w BOOKS

SRS

Comments are closed.