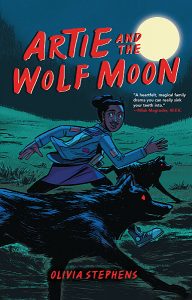

Growing up is tough enough without discovering you’re descended from a long line of mythical creatures. Just ask Artemis “Artie” Irvin, the star of Artie and the Wolf Moon, the debut middle grade graphic novel from cartoonist Olivia Stephens. The story follows Artie on a journey of discovery as she learns that her mother is a werewolf — and that she is, too. The revelation leads her to a new found family, new threats in the form of vampires, and a new level to her relationship with her single mother, Loretta.

With Artie and the Wolf Moon in stores this week, The Beat had the opportunity to chat with Olivia Stephens about how she developed the book, why she went with werewolves, and how her experience creating a full-length graphic novel differs from her previous work.

Joe Grunenwald: Of all the classic creature types, why did you choose werewolves as the focus for this book? How did you decide what aspects of traditional werewolf ‘lore’ to keep and where to add your own spin to it?

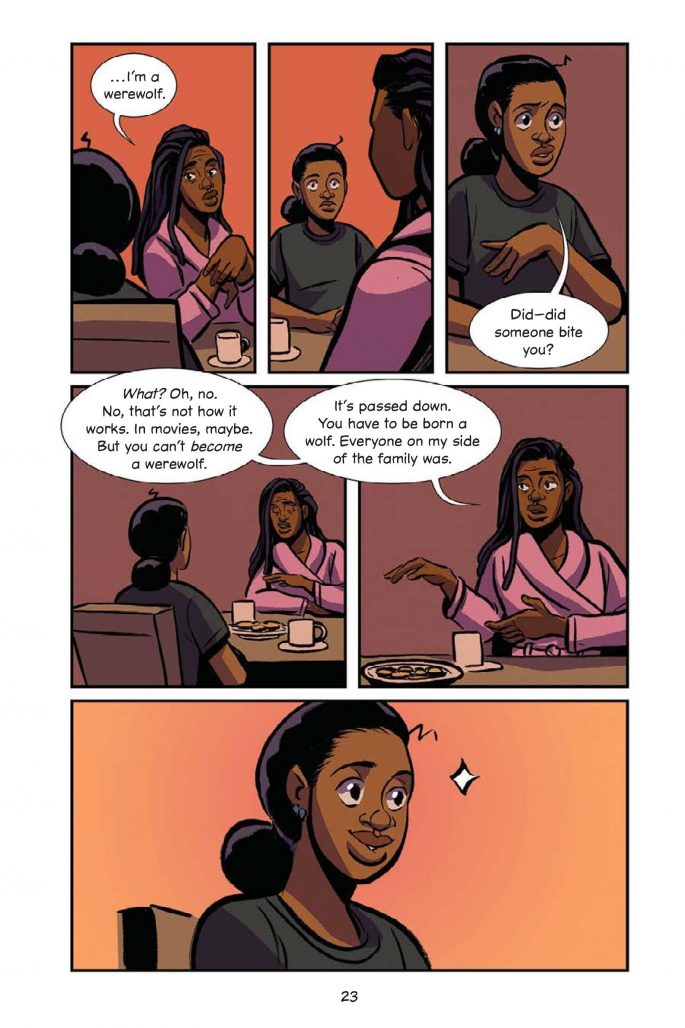

Olivia Stephens: I’m really drawn to the werewolf having a real-life counterpart, especially since actual wolves are radically different from the narrative that’s been placed on them. Real wolf packs are organized like families, with parents leading their offspring. I wanted to reshape the idea of werewolves around the concept of family. And that’s the framework I used to mold existing lore into my story. I shifted things like the full moon into the space of a historical and cultural marker, rather than an impetus for transformation. All of those decisions were in service to viewing the werewolf through that familial lens.

Grunenwald: Artie’s relationship with her mother is a key component of the book. How much inspiration did you draw from your own personal relationship with your family?

Stephens: I have a pretty different relationship with my mother compared to Artie and her mother, Loretta. My mother and I are very close and I share nearly everything with her, to the point where there’s really not much for us to talk about during a number of our Skype calls. So we enjoy a lot of silence in each others’ company on days when I’m not spilling my guts.

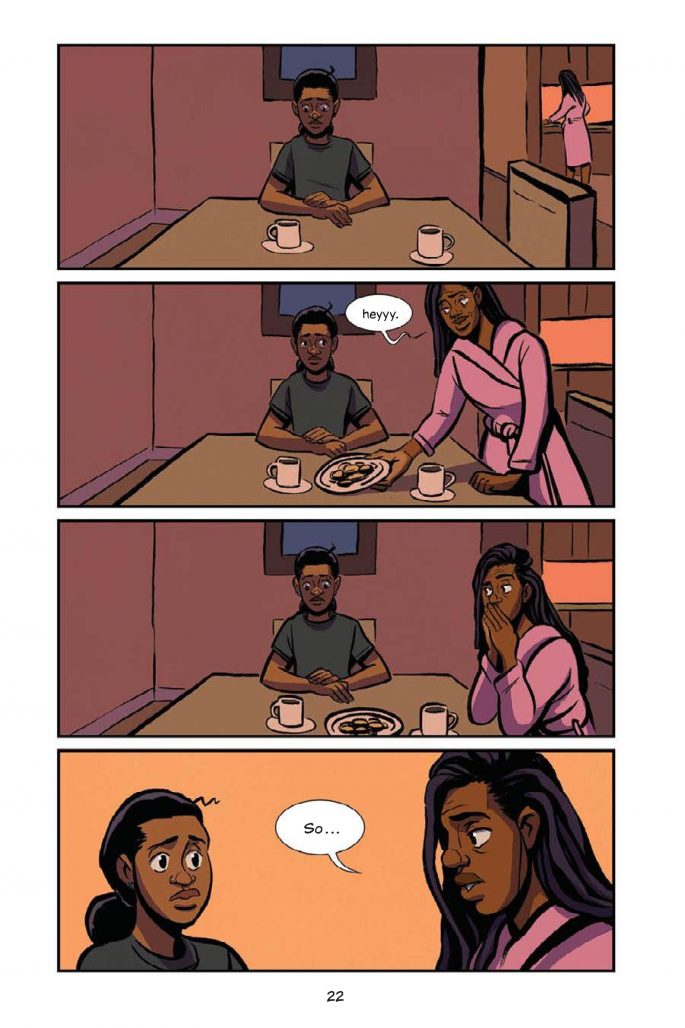

Artie’s relationship with Loretta was an interesting departure for me because there’s so much that they don’t share with each other. Loretta is especially guilty of this, obviously. There’s so much left unsaid that actively harms their ability to understand each other. So it was fun to write how that dynamic changes after Loretta’s secret is unveiled at the beginning.

Grunenwald: Artie dabbles in photography, using her father’s old camera, which still requires film. Are you into photography yourself, or did you have to do any research on the topic for the book?

Stephens: While I was developing the pitch for the book in my final year of art school, I was also fulfilling the last of my out-of-major course credits. I ended up taking Introduction to Darkroom Photography and going through the process for film was very meditative for me. I was in the darkroom one night thinking about Artie’s story when I realized I could use the darkroom and film development to frame the story and Artie’s relationship to her father.

Grunenwald: You shift your art style during the Mother Werewolf sequence. The visuals during that sequence are very striking. How did you decide to make that shift, and did you draw inspiration for that style from any particular sources?

Stephens: I decided to use quilts as a storytelling tool within the werewolf community after reading about Harriet Powers, who was a folk artist born into slavery. Harriet documented local legends, Biblical events and celestial events through quilting. I saw an opportunity for the quilts to provide a variety of uses in Artie, since the werewolf characters need something to cover themselves up after shifting back into human form. So they’re used for warmth as well as preserving their stories. Powers used more simplistic shapes in her designs, but the art for the Mother Werewolf sequence (and the general werewolf “folk art” in the book) was also heavily influenced by the work of Aaron Douglas and Jacob Lawrence. Both of them interacted with Black historical events in their work, using incredibly dynamic shapes and color to do so. There’s a particular painting of Douglas’s called Into Bondage that I was drawn to for the way it utilizes the color blue and his signature “halo” effect:

Grunenwald: As this is your debut graphic novel, did you learn anything while working on this project that you didn’t expect to? How did developing this book compare to working on shorter projects?

Stephens: I learned (the hard way) that short comics are sprints, and graphic novels are marathons. Because it was my first time tackling a long-form project as opposed to short stories, I only had the skill set for “sprinting”. But you can’t really sprint your way through 250 pages. My major stumbling block was learning how to pace myself and expedite my creative process for the volume of work involved. You have to shed a lot of the preciousness you might have over your work in order to get the story done, because you won’t have time to make every page perfect. Done is better than perfect, because perfect never gets done!

Grunenwald: Finally, what do you want readers to take away from reading Artie and the Wolf Moon?

Stephens: I want readers to take away the importance of building and maintaining relationships that feed and sustain you. No one gets through life alone, and we need to rely on each other to make it through our darkest moments. Sometimes you will need a shoulder to lean on, and other times you will need to be the shoulder for someone else. That is the beauty of our interconnectedness.

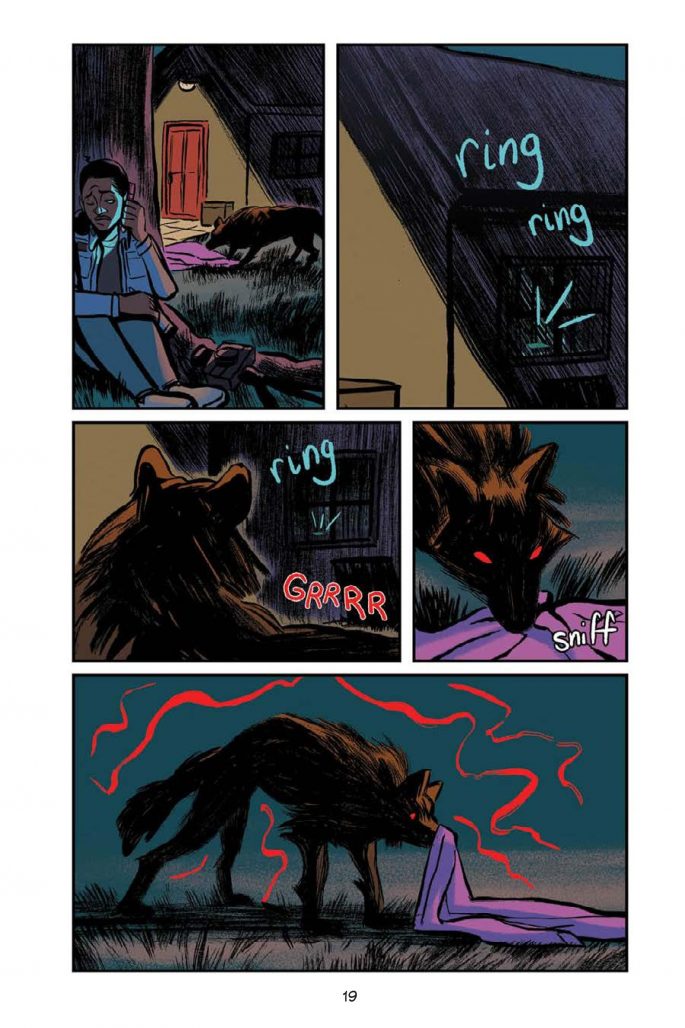

Published by Lerner Publishing Group’s Graphic Universe imprint, Artie and the Wolf Moon arrives in bookstores on Tuesday, September 7th, and in comic shops on Wednesday, September 8th. Check out a few more preview pages from the book below.