On Thursday at New York Comic Con, the New York Public Library hosted a panel that centered on the portrayal of mental health in comics and how comics offer a unique opportunity to get inside the minds of its characters. The panel was titled “Comics and the Clinic: Comics and Mental Health in Practice,” and featured moderator Valentino L. Zullo with panelists Jeremy Whitley, Vasilis Pozios, and Vera J. Camden.

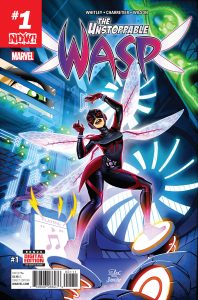

Whitley explained that he talked with an editor about it and they chose to wait until the second volume because they didn’t want to define Nadia by her disorder. However, before the series reached a second arc, which meant the book was cancelled before Jeremy could write the story he was most excited to tell. But Unstoppable Wasp sold so well in trade paperback that the comic was brought back.

Whitley said that discussion about Nadia’s bipolar disorder started very early on, and the first volume hints at it by addressing her family history. Her father, Hank Pym, starred in comics from the 1970s that portrayed mental health in very questionable ways, and writers kept redefining Pym. In a recent storyline, Marvel finally landed on bipolar disorder as his specific diagnosis. Because her father suffers from the disorder, it makes sense that his daughter Nadia does as well.

Unlike her father, Nadia’s defining characteristics are that she’s happy, optimistic, and positive. Because she wasn’t already stigmatized like Hank Pym, Whitley said he wanted to show that people who are generally happy can have mental disorders, too.

Whitley worked with a lot of consultants when writing Unstoppable Wasp so that it would read authentic in not just how she acted and reacted but how others did to her. In a lot of stories about mental health, the character apologizes and suddenly everything’s okay again. But Nadia damages relationships with her friends because she stepped over some boundaries, and everything isn’t fixed with a magic wand.

A similar question is whether characters should be forgiven for bad behavior due to their mental illness. When considering Hank Pym’s past, Whitley decided that he’s not easy to forgive because he hasn’t made an effort to seek help. Instead of addressing his problems, Hank endangers the people around him because he believes he can do it all himself.

The conversation moved to the use of thought bubbles (or lack thereof) in comics. Educator and editor Vera J. Camden referred to them as avenues into the mind of comic book characters. She loves how in comics the reader and writer have access to their interior states. Through images you access the mind in ways impossible through straight prose. She worries that, by pushing out thought bubbles, publishers and creators push out a place for internal rendering, especially the mindspace of young children.

Whitley said that he uses captions as substitutes for thought bubbles. He thinks that writers and editors moved away from bubbles because they used to be very wordy, namedropping Chris Claremont. He also said that Marvel editors are often against captions, as well, because they think it better to lean on the artists to depict how the characters feel, though he believes that one doesn’t have to be at the cost of the other.

Vasilis Pozios has worked with prisoners to explore themselves through the making of comics, saying it’s a great avenue because of what the other panelists said about captions, and because comics often tell stories about events that change people’s lives. That’s the kind of story that prisoners yearn to read while they’re behind bars.

At this point, Valentino opened the panel up to questions from the audience. A young woman asked about the narrow line between telling a story and simply conveying information. Camden was very opposed to comics that inform, believing them to be manipulative and disparaging to the artform. The panelists discussed how, with anything that’s hot, outsiders will try to use it to make a buck. One example they gave is comics that explain how to take a pharmaceutical. Pozios said that he saw someone cosplaying at a psychology convention as a new character in order to advertise a new medication.

Whitley said that, no matter how much time and research, it can be tough to find a happy medium between instructional work and comics that tell new stories. One difficulty in the industry is that a lot of white men in comics want to do something that’s good and provides representation, but won’t listen to the feedback of the demographic they are trying to represent. He thinks there’s something fundamentally wrong with creators who are not willing to listen and learn. If they want to tell a story that isn’t theirs to tell, they owe it to the owners of those stories to get things right. He personally does so to ensure he doesn’t cause more harm than good. He’s currently working on a graphic novel starring a non-binary character.

Whitley said that he asked for notes on his writing from a non-binary friend and, seeing how passionate they were about the project, asked if they wanted to write the graphic novel with him. Whitley wants to see more of that. He said he writes stories that fill a hole, focusing on characters not seen elsewhere in fiction, but he believes it better when someone can write about those characters from personal experience. He takes issue with large companies that have the resources to find creators with those perspectives but choose not to, likening it to casting The Daily Show without searching for a number of different voices. Those executives are letting down the people they want to represent by choosing not to include them in the process.

Comments are closed.