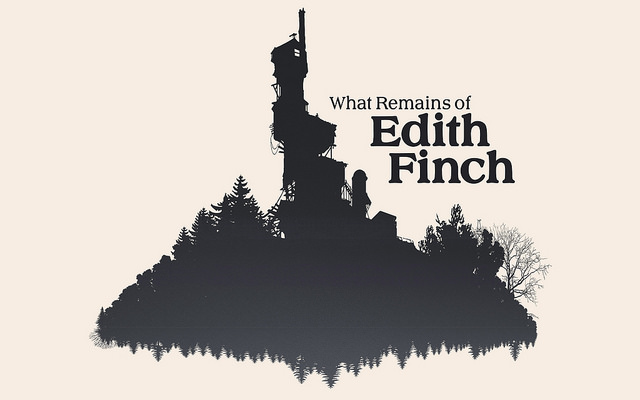

It’s been a bit since we’ve talked about the things that aren’t people in capes punching each other. Today we’re back on track, bringing you one of the year’s most haunting stories told in video games. What Remains of Edith Finch is developer Giant Sparrow’s (published by Annapurna Interactive) follow up to their critically acclaimed debut The Unfinished Swan. While the first game was a unique tale of an orphan boy who navigates a literal blank world by throwing paint everywhere, What Remains of Edith Finch is an eerie beautiful collection of stories about a cursed family house in the pacific northwest. You’ll step into the shoes of a young girl who returns to her childhood home to learn her family’s tragic history that’s something out of a Lewis Carroll fairy tale. As you enter the world of each story you play through different eras and endings that befell various members of the Finch family. One moment you’re a helpless baby in a bathtub, then in another you’ll play as a Hollywood starlet, along with a family tree worth of tales in this poignant piece of art. These stories take you on a journey as you add up all the dots that will make up Edith’s ultimate fate. By the end, you’ll be floored by just how powerful and breathtaking video games can be when they step aside to tell a proper story.

With the game’s release last week, we were fortunate enough to catch up with Giant Sparrow’s creative director, Ian Dallas, to talk about what was behind the story of the company’s new tragedy.

Comics Beat: Where does the idea for What Remains of Edith Finch come from and how soon after The Unfinished Swan did the team know that this would be its next game?

Ian Dallas: The initial inspirations for this game was what it feels like to experience the sublime, moments that are simultaneously beautiful and overwhelming. For me, the first thing I thought of was SCUBA diving, which I did a lot of when I was growing up, and particularly the feeling you get when you see the ocean floor sloping away from you into a seemingly infinite darkness. It’s an experience that makes you feel very small and powerless, but also connected to the vast, unknowable universe around you.

We began working on the game right after we released The Unfinished Swan. Maybe a little before, actually. A few months before our first game came out I was in Seattle at PAX showing off the game and afterwards I took a few days off to hop a ferry and visit Orcas Island, which is where What Remains of Edith Finch takes place.

CB: For someone who’s never played a video game, but is an avid reader, how would you sell them on What Remains of Edith Finch?

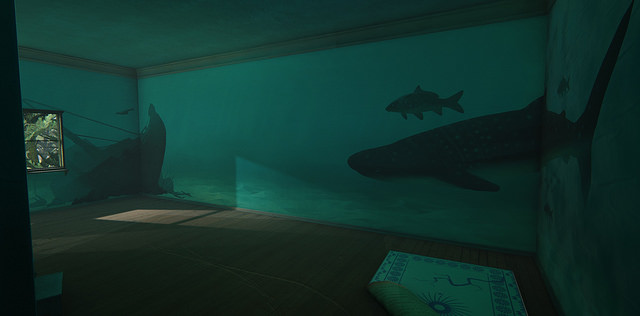

ID: I’d show them a screenshot of the inside of the Finch house, with books stacked everywhere, to help show how important books are to the Finch family. It’s a story that’s very much about stories. From the very beginning of the game you’re hearing Edith narrating from her journal, describing the story of how she returns to the house she grew up in, but then very quickly she transitions to telling stories within that story, about what she’s finding out about each of her family members. If you’re someone who’s interested in stories and in storytelling, there’s a lot here for you.

CB: What makes Edith Finch a compelling character?

ID: I think it helps that she’s got a clear goal (learning more about her family history and why she’s the last one left alive), and that because she’s narrating so much of the game you start to get a sense for who she is and what she cares about, but the way that gets revealed is very gradual, and indirect, so she herself is a bit of a mystery.

CB: From a strictly storytelling perspective, how do you create surprise and tension in each story Edith explores when the player already knows that character in each is going to die?

ID: Knowing that the character is going to die by the end of the story actually makes things easier for us in a lot of ways. In most games players spend a lot of energy trying to avoid dying so they’re always a bit distracted. Since players don’t have to worry about that here, It frees up some mental space to focus on other things, like wondering about character motivations or just enjoying what’s happening in the moment. It also gives us a chance to have two separate emotional threads running in each story, where the story itself is often joyfully describing the way this family member was pursuing and succeeding in whatever their goal is, while meanwhile players themselves are getting increasingly concerned that all of this is leading, inexorably to their destruction. It gave us a way to call attention to the inevitability of death without us having to be heavy-handed about it, since it’s all coming from the players themselves.

CB: What is it about video games that makes it the right medium for a complex story such as What Remains of Edith Finch?

ID: In terms of its complexity, one of the great things about telling this story in a videogame is that we can give players a choice about how much they actually want to dig into that detail. Some players would rather waltz through the stories and race to the end of the game, hitting all the high points without lingering anywhere, sort of like just eating the filling out of an Oreo. Other players are the opposite, and anytime they hear a new family member mentioned they can open the pause menu to look at the family tree and see how they’re connected to everyone else, or when they enter a new bedroom they can spend a few minutes peeking into all the corners and trying to figure out what kind of person they were. I think the nice thing is that the game doesn’t force you to care about the more complex aspects of the story, but they’re there if you want to explore them, and even if you don’t you at least get the sense that these people are like a real family, with a lot of very different threads running through their history.

CB: I’ve read a few of the lighter things you’ve written, banter between a lion and a penguin, even Seinfeld-like observations about the world. Would you ever consider creating a story driven game that’s a comedy or are you content with making your audience tear up like sobbing children?

ID: My hope is that we can do both. I’m drawn to the absurdity of life and I think a big part of that is the range of experiences we can have as human beings. Most games, for very practical reasons (like that you spend 90% of the game carrying a gun and shooting people) have a narrow emotional range. As I get older, I’m more interested in experiences that are a little confusing but give us the space to reflect and begin to empathize with the characters even if we don’t agree with them.

Games that are focused primarily on comedy tend to be as distant from their subjects as games that are focused on combat. I think The Stanley Parable is a good example of that, where there’s a palpable gulf between the player and the narrator who’s constantly making jokes. The need to constantly be making jokes in comedy games sets up kind of an adversarial relationship with the characters. I’d be more interested in comedy that comes out of the painful humanity of the characters like, say, This is Spinal Tap or The Jerk, but I have no idea how you’d do that in a game. Until I do, I’ll go on making these surreal hybrids that blend the terrors of the unknown with the delight of the utterly ridiculous.

CB: In between the time we’d talked with Ian and the publication of this interview, I finally got a chance to finish the game. I can tell you without a doubt, What Remains of Edith Finch is one of the most emotionally breathtaking stories of the year in ANY medium and one that invites anyone who’s never even played a video game before on the journey. The game is available now on PlayStation Store and PC.

If you don’t believe Ian and the team at Giant Sparrow know how to tell a story just take a look at how they adapt the comics medium in one part of the game that explains the fate of Hollywood star Barbra Finch: