(Warning: Disturbing images and spoilers for Midsommar ahead.)

Ari Aster’s Midsommar is not afraid of light. It follows a group of students that travel to Sweden for a midsummer festival that celebrates life with ritualistic killings, communal violence, and hallucinogenic concoctions. Much has been said about its reliance on broad daylight to make its most harrowing sequences transpire in detail and full color. This isn’t a movie about what the darkness hides rather than what happens when horror is unafraid to be seen.

Comics follow a similar path with horror. They rely more on tension, on making the reader feel unsafe. We might see the monster coming up in the following panel, just out of the corner of our eyes, but it’s not about the jump scare. Instead, it’s about the dread comic readers can feel precisely because they already know what’s coming. They might have seen a skeleton drenched in blood immediately after they flipped to the next page, lurking around panel 3. That doesn’t mean the scare’s spoiled. It means that that image, that bloodied skeleton, better be one hell of a sight because of the buildup to it. And if it is, then that sense of unease horror excels at will set in.

Watching Midsommar, I was constantly reminded of horror comics. For every head that burst open in the movie I remembered being repulsed by a Charlie Adlard zombie, either almost fully dismembered but still hunting for food or jawless but still struggling for a bite of human flesh. I felt the connection between Midsommar and comics horror was there when each of the movie’s ritualistic deaths were framed in the clearest form possible for the audience to see. We knew something horrible was coming, but what was truly horrifying was just how much of it we were allowed to see, which is something we’re usually treated to in comics.

Horror in comics tends to be an exercise in tension and dread, two things that Midsommar excels at (although not only just that, but they are overarching). Given comic book panels contain images that often leave little to the imagination (which is not a bad thing in the slightest), horror stories tend to favor a very freestyle approach to mood, setting, and coloring. One of the best examples of this is Emily Carroll’s Through the Woods, a graphic novel containing five horror stories inspired by old fairy tales and the works of Edgar Allan Poe.

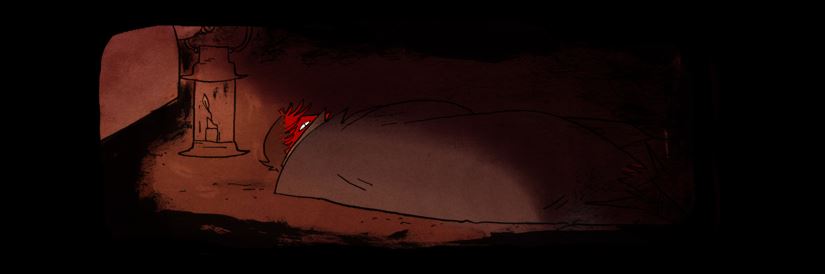

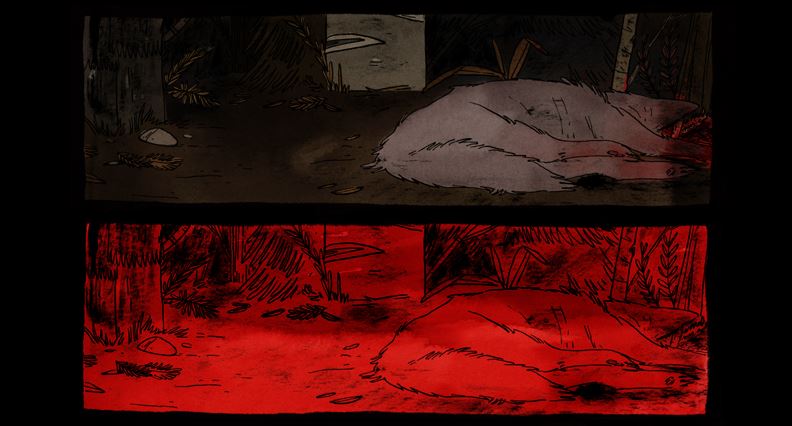

Carroll uses colors to shape the horror in each of her stories. Solid reds, hazy blues, and greys are all paths that lead to an unsettling reveal. One story, titled His Face All Red, follows a man who killed his brother only to see him come back as if nothing had happened. When the brother was killed his face was red. By the end of the story, when the man goes to confront his brother we’re met by a face, covered in red, laying down on the hole his brother buried him in.

Before the reveal, Carroll makes sure the color red is featured prominently throughout the story and it results in creating a feeling of dread that follows through till the end. By dread I mean a feeling of something being wrong not just for a moment but throughout the whole story. Each splotch of red, each hint of it, is a sign of terrible things to come. It creates tension. M. Night Shyamalan’s The Sixth Sense sees a similar color strategy employed, with the color red announcing the coming of something scary (a ghost in this movie’s case). Midsommar does this by sticking to the brightness of summer days, when nature’s green is in full force and the sky’s blue reminds one of paradise. Those colors become unsafe, dangerous even. They do not communicate peace and tranquility anymore.

Midsommar achieves dread by making sure the festival-goers are present in almost every scene. Their pure white clothing, their runes, their eagerness to be in constant dance or bizarre meditation is truly unsettling, and it never lets up. But it is that overabundance of white that serves as that insistent reminder that things are never right. When that white is smeared in blood, the effect is heightened and it creates its own horrific color palette.

One of the best uses of these elements in Midsommar can be seen in the cliff scene. Elder commune members that reach the final phase of their lives must commit senicide, a real ritual practice seen during prehistoric Nordic times in which elderly people who could not survive on their own threw themselves, or were thrown, from a cliff to their deaths. In the scene in question, our main characters, unaware of the ritual’s purpose, see the curtains pulled all the way back on the commune. There is chanting, dance, the white clothing, flowers, rune stones, blood on rune stones, a bright sky, a whole set of images that just scream paganism, all leading to an old man and an old woman jumping off the cliff. The woman’s head bursts. The old man breaks his legs but lives, which requires someone bash his head in with a giant wooden mallet.

Nothing is left to the imagination, but that moment brings the movie’s dreadful build up to another, more heightened, state of fear. The blood on the stones, on the white clothing, the commune’s chants, and all the colors the light allows us to appreciate add another layer of terror to the already mounting dread of the festival. This sequence brings it all together and unleashes the commune’s brutality, still at a slow pace but with chilling certainty. Like Through the Woods, Midsommar creates a color pallete that is highly communicative of impending horror.

Gail Simone’s and Jon Davis-Hunt’s Clean Room is another horror comic I thought about during Midsommar. This comic shares the cult part of the story with it. It follows Chloe Pierce, a journalist that can see some truly sadistic-looking creatures in a world where very few can. She is investigating a self-help cult led by a strange guru called Astrid Mueller that is playing a dangerous game with things not of this world. Clean Room, as in implied in the title itself, also finds in light and colors a source of pure horror.

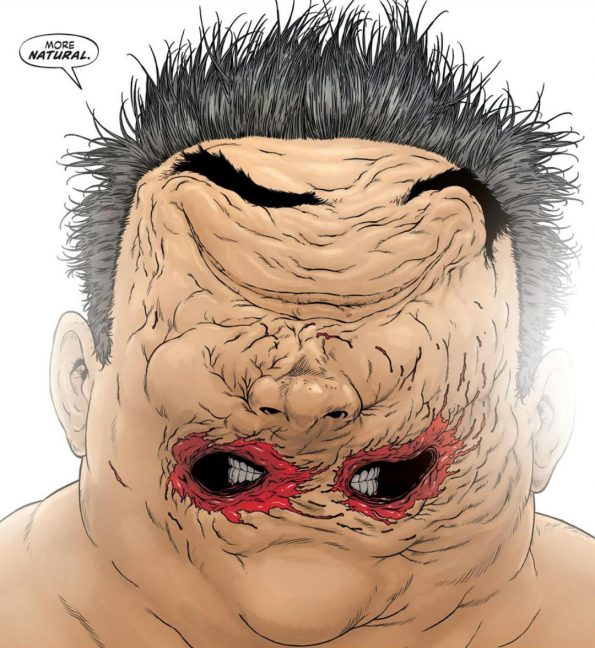

The comic’s creature designs are a hellish blend of insect appendages and demonic vibes and they are often let loose on humans in disturbingly imaginative ways. Through them, we see human skin being contorted in impossible ways and razor-like bone structures protruding at weird and painful angles. There’s a lot of John Carpenter’s The Thing at play here, but what again puts this comic in league with Midsommar is its indulgence in detail and its lack of restraint when showing things that are truly horrible.

There’s a scene in the movie where we get a glimpse of a member of the commune wearing the skin of one of the visiting students. The camera lingers for a bit and we’re invited to really take it all in, maybe even try to guess whose skin is actually being worn. Clean Room does this consistently, inviting the reader to make sense of its creatures. One such creature is wearing someone’s face upside down, showing its teeth through its eyeholes. It took me a bit to figure out what was going on. Once I did, the image stuck with me and it ramped up the horror for the remainder of the series, considerably.

Clean Room’s creatures don’t always come out of dark corners, but instead materialize or transform under a heavy light source. We see creatures with pinkish skins and deep red husks whose mere presence injects the comic with even more dread. It gets to point of feeling oppressive, but not in a way that discourages reading. It helps one get more invested in the characters to see if they find a way to rid themselves of these monstrosities. Midsommar definitely likes to oppress as well. As the commune shows its true form, the light and the colors become part of the horror. It gives the concept of hell a whole new dimension, with lights and colors being new allies.

This is by no means a look at the only comics or movies that extract horror from light (see George Romero’s Dawn of the Dead and Day of the Dead movies or Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre for other great examples of this). Midsommar is just a very strong reminder horror can also lurk in the absence of darkness. The comics mentioned here are evidence that this type of horror has been making it rounds for longer than some might think. Maybe after watching the movie, give one of these books a read if you haven’t already and try to hold your gaze firmly on one of its monsters. You might find yourself turning the page much faster than anticipated.

For more on Midsommar check out The Beat’s review of the film here, written by Hannah Lodge.

Comments are closed.