Steven Sanders was one of the first people I ever interviewed. An artist and designer who has worked on books such as Five Fists of Science, SWORD, and Our Love is Real, I’ve always been struck by the amount of thought he puts into his character and concept design. When I think about design in comics, his name is always the first I think of, and you can find a long, astonishing gallery of his work and ideas over on his website. So as I started making up a list of people to interview for The Beat – editors, letterers, colourists – it was pretty clear that there was nobody else to come to for a discussion about the design process in comic-book art.

Thankfully he agreed, and his answers are – as they’ve ever been – absolutely fascinating. Hope you enjoy!

Steve Morris: When you’re first given a brief like the new design for The Silver Samurai, how do you start? Do you look for realism or fantasy in the design?

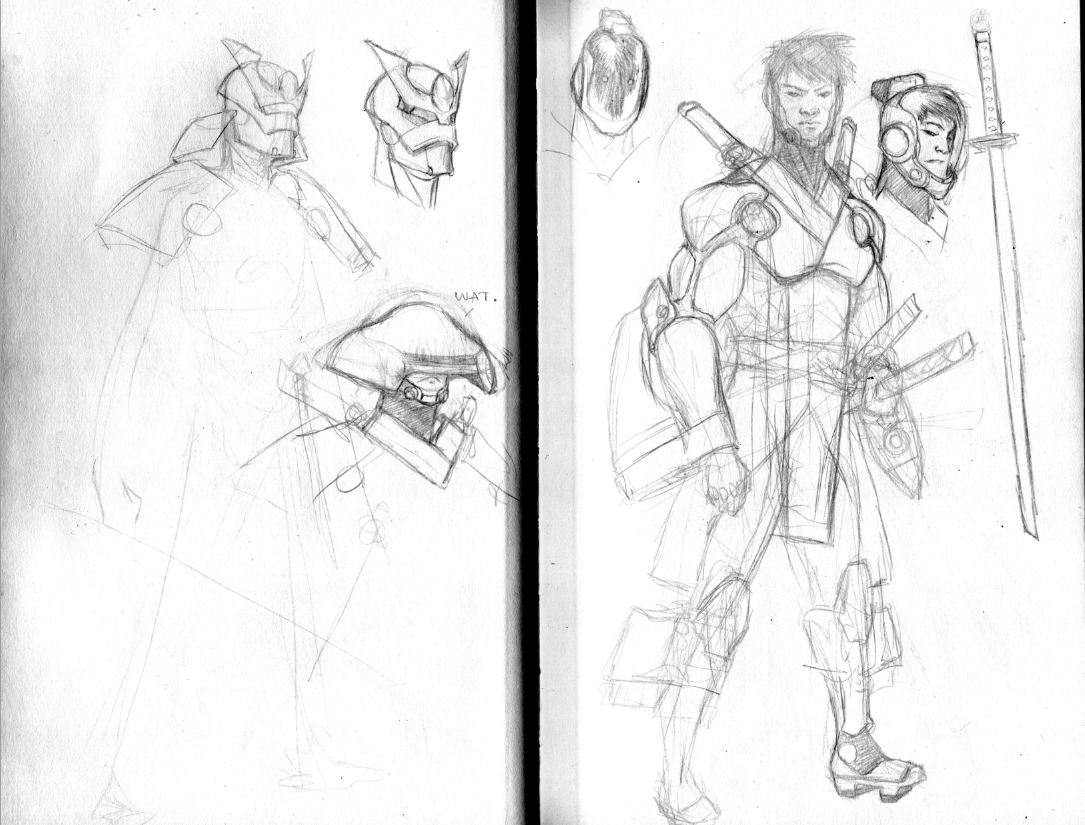

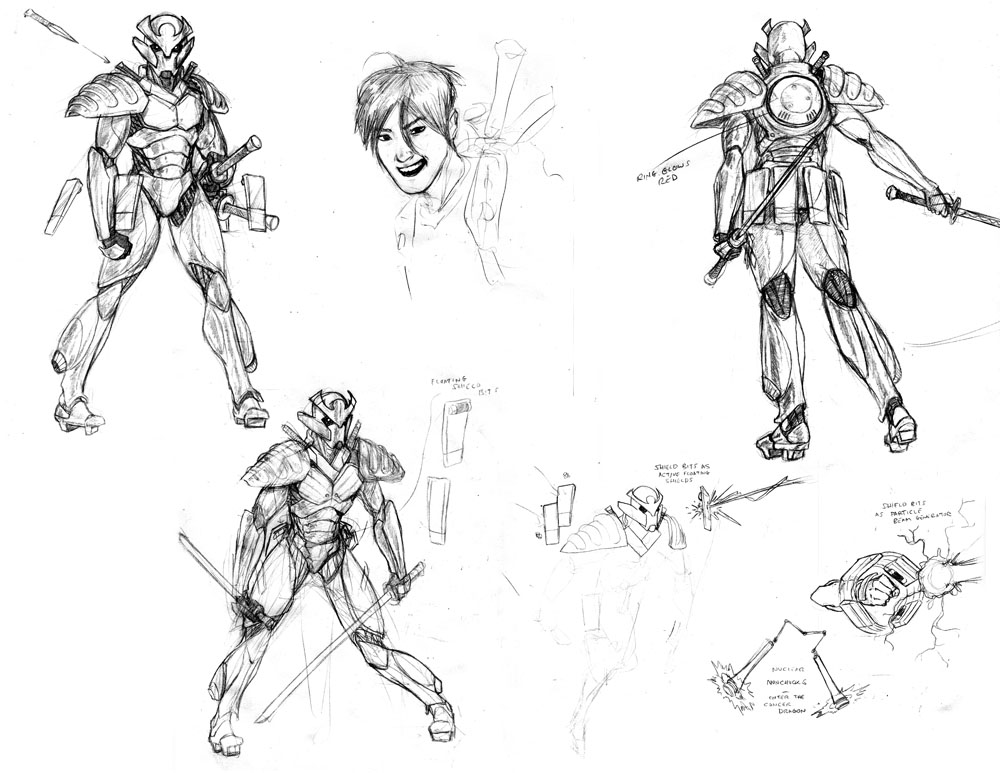

Steven Sanders: I usually just try and find everything on the internet, in books, or in my memory that I possibly can that relates to the character (in this case: samurais) and then let my brain chew on it for a day or a few hours and then just start sketching things out.

The anime Samurai Champloo was a big early inspiration for the new SS design, as I (and Jason Aaron, and editorial) wanted to get away from the old clunky warring states period style of armor. As far as realism or fantasy, it mostly depends on the character. I went for a blend with the new SS.

Steve: Do you ‘pitch’ designs back to editorial, in a sense? Do you try different versions of the same character and see which ones they like best?

Steven: Sometimes yes, other times they just say “Draw this thing” and I do it, and assume they’ll tell me if they want a change. The Silver Samurai design was one of lots of back and forths and tweaking, but it was all pretty minor stuff.

My initial sketches for SS came after watching Samurai Champloo again, and I just kind of let my brain churn out whatever it came up with, then narrowed it down from there.

I had the initial “final” with geta style shoes, because one of the characters in SC used them as an entangling device in sword fights, which I thought was clever. But that was nixed as looking too goofy/the mainstream audience not really understanding the point of the shoes. Which I think was fair. I don’t really have my finger on the pulse of the American comic scene anymore, so my perspective is likely skewed.

Steve: I know you do a lot of research into the science for concepts like space travel, robotics, and the like. How do you think that aids your work?

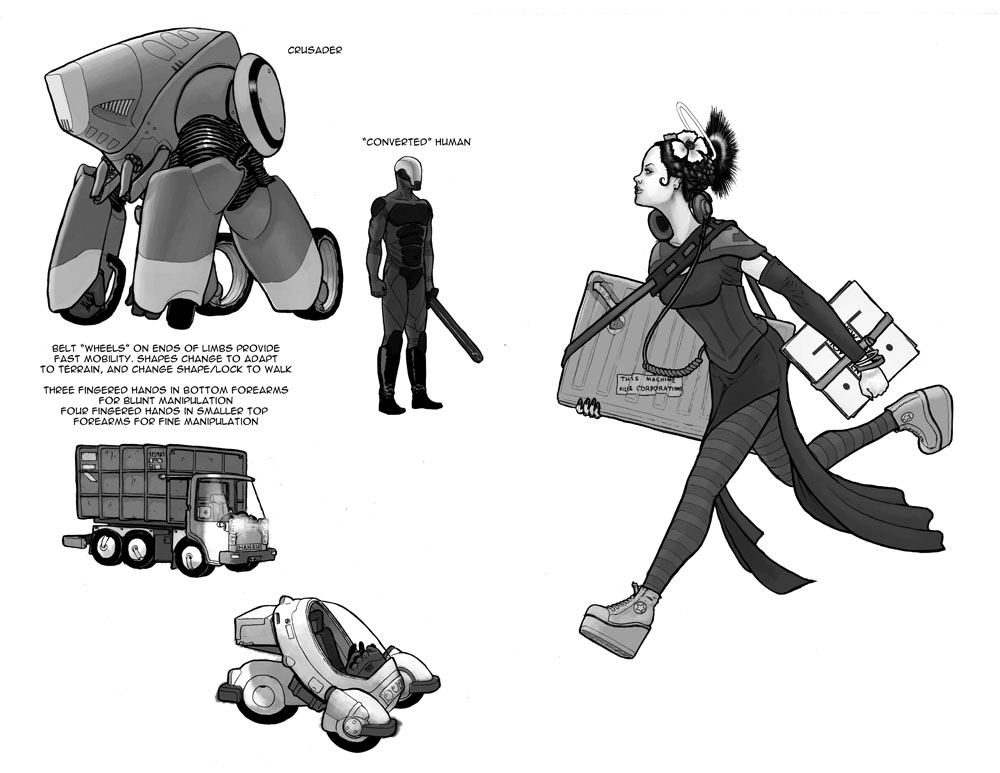

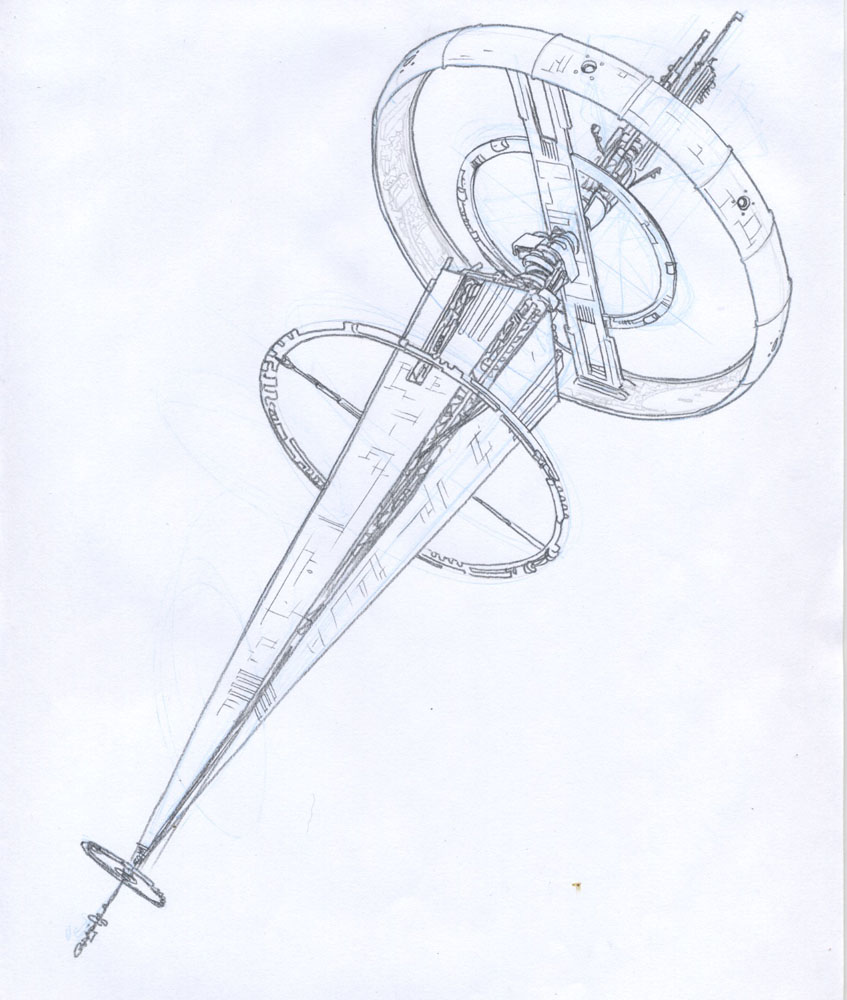

Steven: Honestly, it’s sometimes a hindrance, as I’ll get into later, but by and large it helps to make a world more robust and concrete. I mean, 90% of what I end up putting into the designs isn’t actually seen/known by the reader, but hopefully it adds to a feeling of “This is a thing that could actually exist.” I try to have every part of a device serve some purpose.

Steve: Is it important to create a set of scientific rules, even within science fiction, and use those to dictate the design? Rules which you stick by, and don’t break. For example – Iron Man could use jet launchers (or whatever he calls them) to fly, but if he doesn’t have them in both gauntlets, he’ll fly crooked and can’t land properly. There’s a set of rules in the fictional science, even if the science doesn’t exist in the real world.

Steven: As far as consistency goes, yes. You can only ask the viewer for so much suspension of disbelief. If your rules are based on non-fiction science and engineering, that can become problematic at times. I’ve become bogged down with designs in the past because I was so focused on making it “real” that I forgot to make it look cool. I mean, you can make the most realistic robot in the universe, but if it looks like a washing machine, that’s not very exciting, is it? I mean, unless you are really into washing machines. I’m not here to judge people.

Steve: On a similar note, how much research has to go into period designs and detail? SWORD was set in space, for example, but then something like Five Fists of Science has a totally different setting and world. Does that affect the way you design technology?

Steven: Yeah, it does. I did a lot of research into early 1900’s medical equipment that uses electricity for FFoS; Tesla’s control-helmet was pretty much a straight rip off of some bit of electro-therapy equipment. But, there were some design choices that in hindsight, and with myself as my own worst critic, could have been less “realistic” and more “cool.” Most of the equipment was very utilitarian, and reflected how they would have built prototype equipment back then.

Most steampunk books give the impression that everything from the Victorian Age had delicate scrollwork all over it. But if you go back and actually look at pictures of the equipment, if it was machinery that was made to do any kind of actual work, or a prototype, it was usually just plain metal and wood. Why put all of this detailing on something that’s just going to get beaten up?

Steve: You’ve also done a lot of work with character design, such as with SWORD. Did you get many notes about, say, Unit, or were you allowed to try things out for yourself and then get feedback?

Steven: Hm. My memory is a bit hazy on exactly how UNIT started, but Kieron and I did do a lot of “hey how does this look?” “Close, try doing this…” before showing it to Nick Lowe. UNIT originally had hair and legs, for instance. Like a robotic Superman without the curl. It was… weird. I don’t know what was going through my head.

Steve: As an artist, what are the most helpful notes to get? Do you want to be given in-depth ideas about the backstory and personality, or would you rather have a basic description you can fill in yourself?

Steven: I consider my main job to be that of making the writer’s script come to life, not to toot my own horn. So, whichever route takes us to that point, I’m good with. Some writers like to put in as many details as possible, others just kind of point me in a direction and say “go nuts.” I probably enjoy the latter more, but, it is more work, and after you’re drawing for 5 hours straight, it’s work no matter how you cut it or how many people think it’s a “dream job.”

When I was working on Five Fists of Science with Matt Fraction, we were both learning our craft, I think, and he gave me very detailed scripts describing camera angles and layouts, which was a huge help in my learning how to make comics. I think I had done maybe 30 pages of sequential work before that, tops. Kieron Gillen and Jason Aaron take a more laid back approach, either because they trust me to do the work right, or they have better things to do than make every script a “How To Draw Comics The Marvel Way” addendum.

Steve: What’s the key to getting a character design right? Can you get to a place where you’re happy with your work, or do you always look for tweaks and changes?

Steven: Ooof. I really have no idea. I guess it’s kind of like the US judge who said that they didn’t know how to define pornography, but they knew it when they saw it. I just scribble and tweak until something clicks in my brain that says “Ok, this is it.” Or at least something close to it. I very rarely make something that I’m 100% happy with. But that tends to come with the territory.

Steve: Do you think it’s important for an artist to stand out and having something unique in their style, when working for a company like Marvel? Your version of Beast was controversial despite being the best ever (or since Frank Quitely at least, it’s very hard to top Quitely), but it also got people’s attention to the series, which they might not have otherwise had a reaction towards.

Steven: I think it’s a double-edged sword. Ideally you want a style that is unique (Or that steals from obscure sources so people think you are unique) but is also “classic”, IE something that won’t look dated in a decade.

The Beast thing was funny. I had read very little X-Men since I was a kid until I read Morrison’s run, and had just assumed that everyone else was on board with the Quitely style Beast. The number of people who were very confused by that character not having a flat face was kind of weird, considering that the Morrison run is considered one of the best of all time.

Steve: Do you find yourself actively looking to reinvent some characters? For me, one of your more notable design overhauls was for Surge, a young Japanese member of the X-Men. It was nothing radical, but you gave her clothing that, y’know, she’s actually be likely to wear.

Steven: Ha! I just try and make people look somewhat realistic. I have a lot of these old photo reference books that illustrators made heavy use of in the 70’s, and that comes in handy for looking up racial genotypes. Artists that can only draw one kind of face or style of eye for women are being lazy and/or need to go back and revisit some life drawing basics. (I trend toward giving everyone longer faces than I should, so I constantly have to check myself.)

Steve: You’ve designed whole societies in books such as Our Love is Real. When you have the chance to reinvent an entire world, do you give much thought to which things would be different, which would be the same, how to distinguish this universe in subtle ways?

Steven: Yeah, I try and do sort of a mental time-lapse growth of an extant city in my head. The city in Our Love is Real was based on Buenos Aires. I looked up a lot of references on the city, and then added markers of future growth to it. The massive spire-buildings, flying transports, etc etc. I prefer that approach as opposed to the “Neo-Tokyo” look, because most cities are sedimentary in nature, unless they have been levelled by some war or catastrophic event.

You know, it’s 2012 and most major cities have a lot of buildings that go back a couple if not several centuries. Sam Humphries gave a lot of great information to serve as a foundation for the world, so that was a big help, too. When working with a writer, their information is always your seed material, so the more they give you that inspires visions in your head, the better.

Steve: It’s fair to say that Moebius was one of the bigger influences on your work. How do you feel his sense of composition and design helped you develop your own style as an artist?

Steven: Oh man. I basically started out in high school as a straight up Moebius mimic. My freshman art class had a teacher that really soured me on art classes, so I just drew during classes that bored me and copied artists I liked. It was only manga that turned me away from Moebius and put me onto a path of “Look for whatever parts in the work of others that you like, and incorporate it into your own.”

I really loved the quiet atmosphere of a lot of Moebius’ books, though. They were serene and detached, only somehow not in a bad way. I had to unlearn a lot of that for doing superhero work, because one point perspective and flat horizon lines don’t cut it with the Big Two. But, when it comes to scenes that call for quiet, or an ethereal feel, I always fall back to his work.

Steve: What advice would you give to artists working on design and concept work, prior to starting a comic?

Steven: Hm. If you’re on a deadline, “Good luck!”

Because it’s pretty hard, at least for me, to devote much time to really digging in and putting a lot of effort into concept design when I’m on an average comics deadline. But, regardless, if you have the time, dig up as much related reference related to the subject matter as possible. That’s the foundation of your work.

Don’t copy whole things, but synthesize multiple objects into new ones. For instance, “I need to design a transport truck” Go and find as many pictures of transport trucks as you can, ideally looking for ones that people are not used to seeing, then cherry-pick your favorite aspects from each of them, and assemble your new truck from that, using the script to inform your choices.

Steve: Lastly – what’s coming up in the future for you? Any new projects?

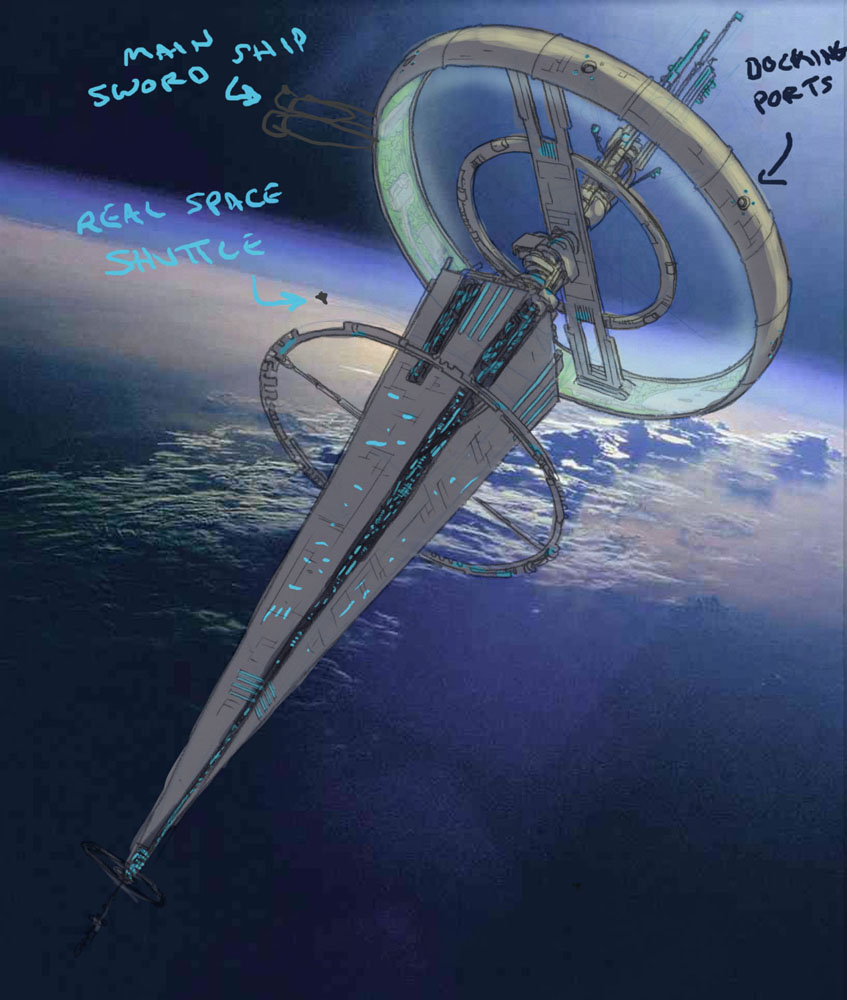

Steven: Nothing comics related that I can discuss yet, but I’m working on a pet project, called “Symbiosis,” where I’m creating a whole world where the things that fuel our technology simply don’t exist. There are no internal or external combustion engines. No electro-magnetic devices. So a relationship has developed with humans and certain kinds of life, where the lifeforms give them useable power (based on a vague “bio-ether” concept I have) in exchange for, say, the ability to move on their own. This is an example: http://www.studiosputnik.com/illustration/images/biowalker.jpg I’ll be making an entire civilization based around this concept, using paintings, sketches, and some sequential pieces.

But it’s not just a book of pretty pictures of tech and landscapes. Something that I’ve had a lot of people tell me is that my drawings make them want to write stories. So that’s part of the purpose of this project. There will be little if any narrative. It will be Creative Commons/CopyLeft licensed, and people can take this civilization, or part of it, and make RPGs, or video games, or novels, or whatever they want. Go nuts. (Just talk to me first if it’s going to be sold.)

I want to get it printed as an 11×17 high-end art book, a much more affordable e-book, prints, and produce a number of resin-cast “artifacts” from the world, to make it more tangible. So I’ll be doing a Kickstarter shortly to see if there are enough people interested in this sort of thing to make it happen. I’ve been kicking this around for years, and am excited to finally get going on it. Should be up within a few months, depending on my finances and work schedule.

The surest way to get more work as a freelancer seems to be to say “Ok! Time to work on a personal project now!”

Many thanks to Steven for his time, and amazing answers. Find him on the Twitters! Or on his website! Or Tumblr! And if you want to find an evening whizz by while you sit in awe, have a look at some of his concept and design work over here!

RT @Comixace: INTERVIEW: Steven Sanders has Designs for the World: http://t.co/nQQUY12Y

RT @Comixace: INTERVIEW: Steven Sanders has Designs for the World: http://t.co/nQQUY12Y

RT @Comixace: INTERVIEW: Steven Sanders has Designs for the World: http://t.co/nQQUY12Y

RT @Comixace: INTERVIEW: Steven Sanders has Designs for the World: http://t.co/nQQUY12Y

Comments are closed.