By Harper Harris and Kyle Pinion

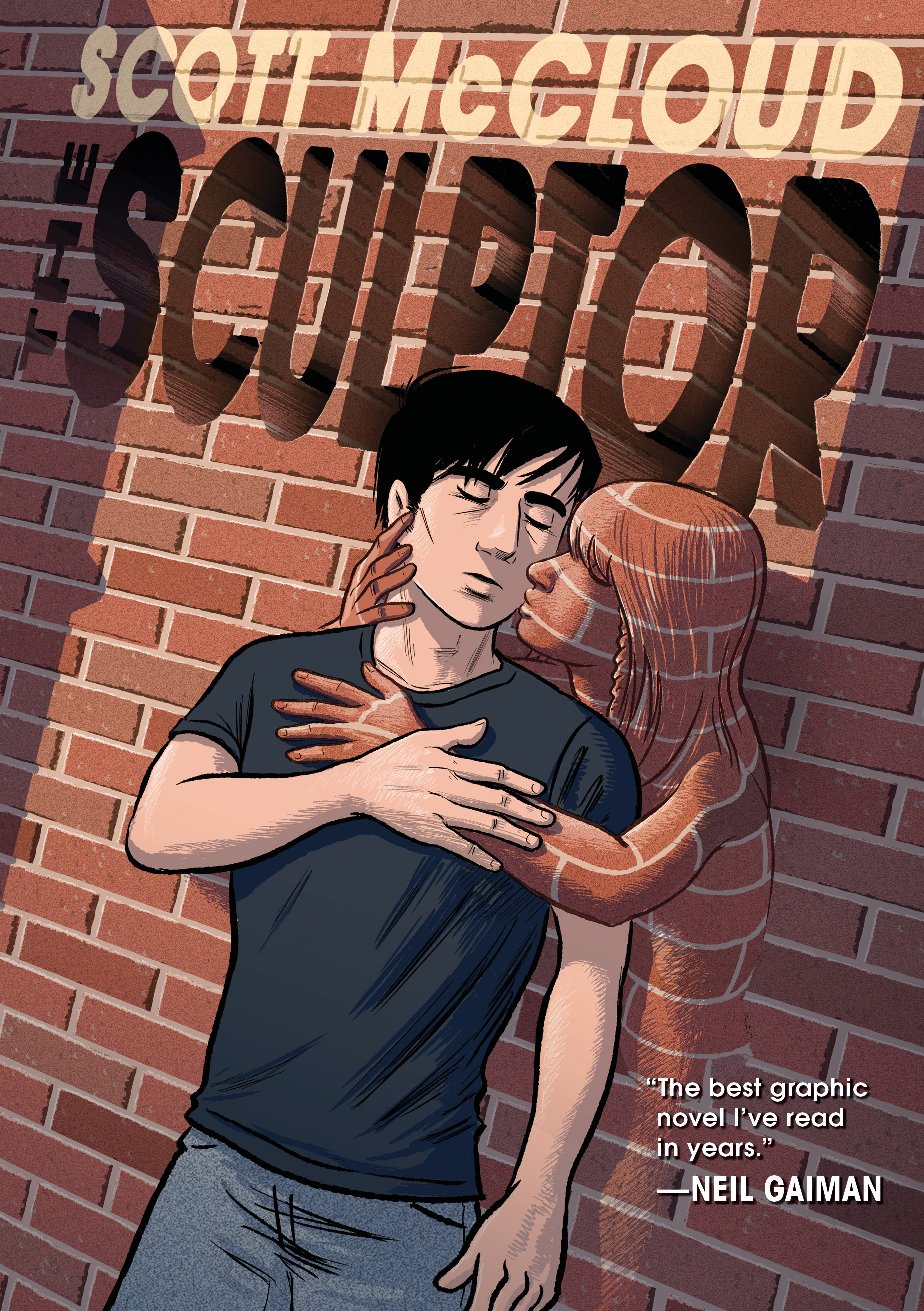

In The Sculptor, David Smith is an out of work artist, who feels as though he never quite reached the level of fame he always thought was right within his grasp. When the physical representation of Death comes offering a deal: the power to sculpt anything he can imagine with his bare hands with the caveat that his life ends in 200 days, David cannot resist the possible benefits of such an ability. The after-effects that this bargain has on his friends, New York City, and his love-life become the center-piece of this newest graphic novel by acclaimed cartoonist Scott McCloud.

30 years in the making, McCloud’s new opus is available on February 3rd through First Second. McCloud was kind enough to sit down with us for a lengthy discussion about the new book, critical expectations, his creative process and how he balances his busy speaking schedule and the creation of a 500-plus page graphic novel.

Kyle: How is the press circuit treating you? I know you’ve been on interviews for weeks now. Are you exhausted?

Scott McCloud: No, I store energy like a cactus stores water and five years squirreled away in my hobbit hole drawing, you store up a lot of energy. So I was definitely ready to come out into the sunlight and talk to people. And the reception so far has been amazing. So far it’s been really encouraging I think is what I mean to say.

Kyle: Well, that’s good to hear. That actually pivots over to one thought that I was curious about. Over the past 15, 20 years now, though you’ve of course published books like Zot! and you did some work with DC in the past as well on the Superman Adventures, you’ve been known as the guy that breaks down comic book storytelling via Understanding Comics and the like. With critical response in mind, did you ever feel a certain level of pressure as someone expected to live up to that analysis with The Sculptor?

McCloud: Oh yeah. There was definitely a big target on my chest when I did this thing, but it was a good kind of

Harper: To delve into The Sculptor itself and how you got started with it, one of the concepts in the book is just how David, an out of work sculptor, feels like he’s got this unrealized potential…he’s got all this creativity stored up and then he feels like he can be this big famous sculptor but he doesn’t have the means to do it yet. As a writer, when you were getting started with this project, do you feel like your creative soul was restless or you had something big you had to accomplish and you just were ready to get it out?

McCloud: I felt like that when I was in my 20s. When I was the same age as David, I felt a lot more like David than I do now. I’ve been lucky because I’ve actually gotten some attention and I’ve been able to get my work out there, but I have a lot of feeling for those who don’t have that, who haven’t had that luck. Whether they’re young and just starting out or if they’ve been at it for 30 years, there are a lot of people who have trouble getting their work out into the sunlight and who rightly feared that their work might be forgotten someday, maybe even in their lifetime. Something that happens to a lot of artists is being forgotten in your lifetime. I can easily put myself in that mindset again of imagining that and imagining that fear, the fear that comes with that. And then the fact that David has this family that’s already gone, both in terms of their physical lives but also in terms of the memories of them, even though they were all three very creative people, his parents and his sister. That made it a much more urgent need on his part to not be forgotten.

Kyle: Now this is a concept that you created decades ago. I think I heard once it was about 30 years ago, is that correct?

Scott McCloud: Yeah, it was really terrifying when I realized it was 30. I was saying 20 and then I think it was Ivy, my wife, just reminded me “nah, it’s actually more like 30.” That’s a long time!

Kyle: It’s a concept that’s older than Harper here actually.

McCloud: It’s older than a lot of readers. It may be older than most of the people who will read this book, some may be younger than the idea for the book itself.

Kyle: I wonder, how has your life experience changed the way you’re approaching the material than if you had written it back in 1980, whatever year it was that you initially thought of it?

McCloud: Well, I think it’s a better book for having been written much later but the important thing for me was I had this young man’s idea and had had a lot of the things we associate with young ideas. It has lots of bold, preposterously ambitious ideas in it. It’s trying to address questions of life and art, mortality, the nature of existence and that sort of thing. I think as we get older, we’re more likely to just address the struggles of getting your coffee in the morning and going to a job you hate or whatever. People tend to scale down their ambitions a little. My goal for this one was to see if maybe I could take that young man’s idea and capture the enthusiasm I had when I was a young man and channel that crazy ambition but channel it in a direction that was informed by the perspective I’d gained as an older man, nearly twice the age that I was when I first came up with it, when I started to work on this thing. And hopefully I’ve been able to do that. To not castrate it, not rob it of the vitality of that young idea but try to preserve the vitality while giving a perspective, direction and a more meaningful shape through what I’ve learned in the intervening years.

Harper: Being that this was an idea that gestated for such a long time and you added things and changed things as you were thinking about it, when you actually sat down to start putting pen to paper and writing it, what was your process like? Were you coming up with a script first, or was it just a rough draft, or were you doing thumbnails?

McCloud: The first part of the process was when I realized I really wanted to work on this book, it was just as I was starting a 50 state tour in support of that previous book, Making Comics, 2006 and 2007. And I was so desperate to

Harper: Why is sculpture was the main thrust of the book as opposed to him being a painter or something that was a little bit maybe closer to your own craft?

McCloud: Well on the one hand, sculpture makes good visual theatre in the sense that it exists in three dimensions, it’s dynamic. The idea of going up against that hard surface, in the case of the sort of things that David is doing, has a nice sense of explosive physical conflict to it. But beyond that, the choice of sculpture as opposed to any other form, I have to be honest, I never even considered anything else simply because that was the starting point. That that was this idea in its original state as it existed in that little three ring binder that I have been carrying around with me since high school where I would write down ideas. That’s where it began, the idea of a sculptor in particular. I don’t really know if it would be quite as effective if it were say flat visual arts like painting or drawing, although interestingly enough, a book that I really enjoyed, Dylan Horrocks’ Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen is I think coming out around the same time and in a way, he does have that notion of the artist being given supernatural abilities of one sort or another, in his case through literally a magic pen. So he gets to explore a slightly different side of that artistic deal with fate.

Kyle: Did you have to do any sort of background research at all?

McCloud: I researched the art world in that area as far as just the cultural and business aspects of it and then just looked at a lot of sculpture. But in the end, I think it’s important to note that what David makes in many ways fails. It fails the test and he’s unable to get a wider audience for it for much of the book. The only things that David ever makes that gain the favor of that world, we don’t actually see. We don’t see the work he makes before the story begins that had gotten him some attention early on, we don’t see the work that he makes that his friend Ollie considers very promising. That stuff is off panel. What I felt I was able to draw or what I was able to imagine is the sort of work that a sculptor might not get recognition for. And so I was able to just pour my crazy imagination into it and then knowing that I wasn’t presenting this as some kind of masterpiece that would be universally acclaimed, I was presenting his sculpture as something that would probably confound or be uninteresting to that world. But I did research some of the experience of living in that world, talked to a couple of people who are part of it. In large part, I was just researching what it is to live in New York in 2000 something because of course this took place over several years and just try to get the city right, just try to show the physical environment of the city as well as the cultural environment.

Kyle: In order for David to gain his amazing abilities, he had to strike a bit of a Faustian pact with the embodiment of death. Do those type of stories fascinate you? It’s basically the fulcrum that this story into motion, at least in the beginning stages before we get to know the characters better. Do you find yourself a fan of tales like The Devil and Daniel Webster and the like?

McCloud: Now that you mention The Devil and Daniel Webster, I actually really enjoyed that but it’s been literally 40 years since I’ve read that one, but I remember really being into it. I don’t know that the story was in any way commenting on those other stories, but in some way, I think the important departure here is that it is a deal with death and that the ultimate result is still oblivion, as shown in the blank pages towards the beginning of the story. Like most Faustian bargains, the ending is not in question, right? You know the final fate of the character. But this time, because of that notion of oblivion rather than eternal damnation, it’s kind of the secular version of that story, isn’t it? And I think understanding the difference between that secular, updated version and versions that are more tied to questions of morality than to questions of existential terror, that was interesting to me. I think that was the main thing was that the way in which the echoes of religious beliefs were resonated a bit through this story, but of course it’s a profoundly non-religious story despite the supernatural element that sets it in motion.

Harper: David can be frustrating at times when he is making the wrong choice, which he does quite often. Did you find it difficult to write a protagonist that has those flaws?

McCloud: Well interestingly enough, David was even less likeable in early drafts of the layouts. A lot of my friends who were reading it over, and my editor, pointed out ways in which he was a difficult character to get into. You can have a character with very negative aspects to their personality who audiences still have a passageway into. That was my goal primarily was that even when David is being frustrating, I wanted my audience to be able to get inside his head, to see what it was like to be him from the inside. It goes in a slightly different direction from the question of likeability. Relatability and likeability, I’ve come to understand are two slightly different things when writing characters. He had to be relatable first and foremost and that was one of the goals that I internalized when I was going through rewrite after rewrite, to make sure that we could understand where he was coming from, and to get a sense of what drove him forward even when he was being frustrating or stubborn. Part of that was understanding the difference between wanting to be remembered and being terrified of being forgotten. They’re two different things. Understanding that difference, I think, was one of my crucial procedures as I constructed and reconstructed this story.

Kyle: I’d like to also talk a little bit about one of the other key themes that hit me while I was reading, you display clinical depression in this book with a lot of nuance and that’s not something you see done particularly very well in really many forms of media – television, film, comics, whatever we might be talking about. How much thought and work went into giving that characteristic to that particular character – or was there personal experience at all involved there that sort of informed how that character was resolved?

McCloud: Yeah, there was a lot of personal experience that went into that and that was crucial to being able to capture those thought processes and the kind of relationship that one might have with somebody going through that. I think in early drafts it felt a little bit more pat, a little bit more like just a mechanical necessity of the plot and I think it gained in resolution and nuance I think with the rewrites. That was something that we were very concerned with, that it not simply be a plot device but that it be part of the texture of the story without necessarily departing from what the story was about. One of the things about getting increasing specific in the portrayal of something like that is that you don’t want the story to become about itself, you don’t want to lose sight of why the story exists in the first place. And so that was the balancing act, making sure that this felt like a real emotional story but an emotional story that existed within the universe of the ideas of the story as a whole.

Kyle: This is strange to say, but it’s probably my favorite part of the book because it felt so real to life.

McCloud: That’s really cool. I have to say, much of what I was doing there was channeling because sometimes when you have direct real life experience, sometimes you just close your eyes and let a character speak from experiences. You can hear the voice in your head. You know what words come next because it’s part of the texture of your own life. It’s not a trick you can do often because you – unless you have profound relationships with many, many people which I suppose normal people do. Maybe that’s just me speaking as an overworked comic artist that I’m only able to slot in a few in the course of a lifetime.

Harper: Looking at taking the writing process into the art process, how much thought goes into the panel to panel storytelling, or the perspectives that you choose, or whether you’re going to have an establishing shot to set the mood first, or whether you just go back and forth between the two characters?

McCloud: Every single composition, every single panel choice and pacing choice was done very deliberately, but always with the goal that it wouldn’t seem deliberate. I wanted this book to feel as if it

Kyle: In looking through the panel compositions, it seems like there’s a push and pull between the opaque and the transparent and one of the things Harper pointed out to me was this really interesting use of how you show distance, utilizing either opaque figures or transparent figures, or to emphasize perspective and focus. Was this a tool you consciously decided to use on the book as a visual theme or is this just a natural part of your storytelling tools?

McCloud: Yeah, I think that’s something that I’ve wanted to try out for a long time but I don’t really know that I ever had the opportunity. Nothing I’d done before would have been appropriate for that particular technique. Part of it is the fact that we have a POV character and with a POV character, you can play with perception and emotion visualized in a way that you can’t with a third party objective: omniscient viewpoint. It’s very manga. Manga was interesting to me for a lot of reasons when I first got into it in the 80s and one of the reasons I liked it was that notion of emotional and perceptional participation. That sense that you are here, you’re part of the story. You are the protagonist. And that was done in a number of ways, sort of sliced up aspect to aspect, pieces of perception of the world around you or moving along with the moving character rather than just watching the character move. There were also all of these emotional expressionistic techniques. If the character was nauseous, for instance, the whole world might become a little bit wobbly around them because you were perceiving the world through their eyes. So I tried to do that and I found with the two colors, there were lots of opportunities to do that. As you mentioned, through transparency, opacity, by using colored contours rather than black contours. I think 100 years of CMYK printing tends to condition us to always have a black contour, but there are plenty of reasons not to. So I use them as depth cues and I use them as you said to indicate the perspective of the character, like when he’s focusing on one particular person at a party and everybody else is dimmed out because we’re seeing his mental map of what matters and what doesn’t.

Harper: I know a lot of your work in the past has been black and white. Was there ever a stage that this book was going to be in color or a different style of color use than the way you used it in the book?

McCloud: No. There were practical considerations of cost but there was also the creative considerations that I really like to do it all myself and I’m a shitty colorist. I’ve never had a good color sense and it looks good to me and then everybody else tells me, no Scott, that’s not good, so. But I can choose from a Pantone swatch book, that I can do. And two colors to me is just a little bit nicer than one because with that second color, I can use it not only for the techniques we talked about but just for the simple utilitarian task of clarifying form. When you have that second color, you can make it more quickly obvious to the eye, even at a casual glance, what the forms are on the page, where are the faces versus the background, where the figures and silhouettes are and sense of depth. All of these things really come into sharp, immediate focus when you have that second color. So there were a lot of reasons to go for it.

Harper: In picking the light blue tone that permeates the book; was that a difficult choice or was that something that as you were working through the art, that was just the obvious choice?

McCloud: Actually in May, when time had pretty much run out and it was time for Scott to pick the damn color, I was in Atlanta at the offices of a company called MailChimp. I had given a lecture there either that day or the day before, I’ve forgotten which. And they very kindly gave me their Pantone swatch book and an hour or two in a quiet room in the offices to just sit and select which color it would be. And I will forever be grateful to MailChimp for saving my ass because my Pantone swatch book was locked up in an office here in California, the office I’m sitting in right now. I had the key in Atlanta and there was nobody there who could go and retrieve it for me and those things are expensive, so thank god that MailChimp came to my rescue and gave me that Pantone swatch book and I was actually to select the magical hue 653. I will never forget that number.

Kyle: Between Serial and Scott McCloud giving them praise, MailChimp is having a great couple of months here. I’m trying to couch my next question as carefully as possible here, because it deals with sort of the latter half of the book.

McCloud: Sure.

Kyle: The actual production of the art towards the end, especially in a selection that is full of a lot of panels, was that a physically stressful piece to produce, especially if you were producing it multiple times in multiple drafts? I’m referring to the very end of the book.

McCloud: Oh yeah. No, I know what you’re referring to and it was tremendously difficult, but it was a kind of difficulty that I had come to relish. I really loved the hard work. The hard work of this book was gratifying work. I loved working hard, I loved being challenged, I loved being forced to do something that I had never been able to do before. That was great. What wasn’t great was the fact that I was straining the limits of my system, that it was taking forever to save these files. It was so complex at 1,200 dots per inch – at least I think it’s 12, not 1,000. I think the book is 12 – 1,200 dots per inch, in RGB no less, even though it was a two color book. The thing was just enormous. Those files were enormous. They were like half a gigabyte each and boy, was it slow churning out these things and saving them. That was the hard part was the waiting. Do I save and have to stop drawing for a couple of minutes or do I wait and risk a lightning storm and a blackout or whatever. That was hard, that was hard. But I don’t know, generally speaking though, the hardest things about this book were also the most gratifying because that’s when I felt like I was really finally climbing the mountain.

Harper: One thing I noticed that I really enjoyed in the storytelling was how you used the gutters as far as for pacing. So the distance between the panels in calmer, normal section of the book, there’s a little bit of distance and there are white gutters and then when there’s these parts that are a little more intense or – for example, when David discovers he has these powers and he’s running home to figure out what’s going on and to try them out, the gutters completely disappear and it’s just this thick black line in between panels. It really changed the pacing a lot and the feeling of timing.

McCloud: As you mention it, I’m not sure that I did this much in my first comic Zot!, but there was a pretty rigorous practical set of standards for when that might happen, when I might go to a different gutter style or when I might go to a bleed, for example. And it’s just like for any given moment in the story, the question was: does it pass the test? Is this the kind of moment where David is overwhelmed by what’s happening, where he’s sent into just an emotional rhapsody of one sort or another, of rage or wonder. In those cases, the borders do collapse to a single black line in between panels and it goes full bleed. All of those are full bleed as well. To me, it feels right. And I guess what it is is I had seen other artists who had done that. Sometimes artists just do that for everything. There are a few artists who always have that single black line and full bleeds throughout an entire book. It just has this – I don’t know, it’s like in Wagner when the extra trombones come in. It just seems to be that orchestral color that tells you that something of great weight is happening. And this is a story where I decided to use the full orchestra, so that was one of my tools.

Kyle: I know you speak to a number of different companies professionally, you’re probably on speaker bureaus and the like…

McCloud: Actually you know what, I’ll tell you a secret. I do it all myself. People just email me and I say well, here’s how much it is and I’m either free or I’m not and then we do it.

Kyle: That’s even easier.

McCloud: It’s incredibly informal, yeah. It’s really weird. I should have representation for it. I have representation for Hollywood, I have representation for my books but when it comes to speaking, I don’t know, I just haven’t found anyone that could do it better. It’s weird. So yeah, I just do it all myself. It’s kind of insane. Although I will say for the First Second book tour and my European tour, February, March and April, a lot of that is delegated to the individual publisher.

Kyle: Of course. How do you balance that schedule with your creative time? Is there a lot of creative time being done in hotel rooms? How does that work?

McCloud: We did a lot on hotel rooms last year when we were doing the technical finishes on the book. In fact, I particularly remember writing the entire book to – was it a Holiday Inn in St. Louis maybe or someplace, but we were driving west and we’d stopped for the night and I actually had to unpack my Mac Pro and the Cintiq and everything and it was finally done and we were writing – we got kicked out of our room. So I actually wheeled the Mac Pro out to where the elevators were and Ivy and I were sitting there and while all of these files are being written to a drive, copied to a drive so that we could run to FedEx and send it out. And we looked like homeless people. Our dog was with us and all our coats and we looked like we had camped out next to the elevator and were asking for handouts or something. But all it was was like I had all of this equipment and all of our suitcases just waiting for a file to copy.

Kyle: I’ve never heard of Holiday Inn ever kicking anyone out of a room.

McCloud: *laughs* They were very sweet, they were very sweet. We just explained it and – but it was just nuts. I mean yeah, we’ve had extreme moments like that where it was just really crazy. But as far as the travel schedule versus the work schedule, I worked 11 hours a day, seven days a week for five years, except for the last year where it was more like 14 hours a day. And then I would still travel but in a given month, if I do two or three lectures, that’s really only, what, six days lecturing, traveling and lecturing. So the six days out of 30 is – is that 20%? So 80% of the time I’m working. Of course, Ivy always makes fun of me for this, is that I will say “oh yeah, I was working except when I was traveling.” And she’s like “that’s working too, you know”. It’s not like when I’m hopping on a plane to give a lecture at Google, it’s not as if that’s not work. Of course that’s work. So yeah, I pretty much only work. But then when the book is done, then we have fun, then we play and that’s what we’re going to do this year.

Harper: Was the publishing deal worked out before the creative process or afterwards? I know you had the idea obviously, but was this something that you presented to the publisher and then you went from there? What made First Second the logical choice for that?

McCloud: Well, we went to four publishers and they were all interested in the book to varying degrees. And for various reasons, we went with First Second, but one of the most important reasons of all was just talking to Mark Siegel and seeing that they were willing to put a lot of resources behind it but they also had that sensibility where Mark – Mark is kind of unique. I talked to some real world class editors but Mark has I think the rigorous demanding aesthetic sense of grand, traditional New York 20th century editor while at the same time, also having tremendous chops as an artist and a writer himself. That’s a very unusual combination to find and it turned out to be essential to this particular book, because I really don’t think anybody else could have pulled this story out of me the way that Mark did.

Kyle: What can your fans expect when you’re on the book tour? Will you be speaking at all or will you be displaying any excerpts at all from the book itself?

McCloud: We’re going to be bringing along visuals but for the US tour, the 14 cities in 16 days coming up in February, which’ll probably be this month by the time this goes out. For those where it’s going to be mostly con

Harper: The Sculptor is a dense book and it’s got a lot of really big ideas and themes about art and life and love and all sorts of different things. What do you hope is the key takeaway or the key message that you hope readers pull from it as they’re picking it up?

McCloud: Well, there will be a lot of talk about the themes and the ambition of the book. I think a lot of people already are looking at it as a bid for consideration as a big, serious book. But, my very first goal for the book, and in a lot of ways still my most important goal, is just to create something that is an enjoyable read, that’s a page turner, that has a kind of narrative momentum that just carries you from panel to panel and page to page. If I can pull that off first and foremost, I’ll be happy. I want it to be something that people really get into, that’s engrossing, that they can lose themselves in. And hopefully something that they can find as a rewarding re-read as well. That’s a lot of stuff in there that I think will become apparent on second reading and third reading.

Kyle: Is this going to mark a trend of more fiction based writing from you or are you going to return to analysis after this?

McCloud: Actually, my next book will be a nonfiction book and it’s going to be about visual communication and some of the common denominators across different disciplines in terms of visual education. I feel as if there are common principles to data visualization, information graphics, educational animation, and educational comics. People in all of these fields I think are knocking on the same door and I think it might be useful to see if I can discern some of the fundamental principles that lie behind all of those disciplines and put them in one work, so that’s the next project. That’ll also be with First Second Books.

Kyle: Lastly, where can people find information about the upcoming book tour? Will that be on First Second’s website or will that be on your website?

McCloud: It’s on First Second’s website now. I tweeted about it just the other day and as soon as I’m done with today’s interviews, I am so finally putting up a blog post on my own front page at ScottMcCloud.com and updating my side bar, which is still telling you all about the things I did last year. By the time people get to hear this, they’ll definitely be up.

You can pick up The Sculptor in book stores or your local comic shop starting February 3rd.

For those who are so inclined you can also listen to the full audio of the interview below:

It’s amazing to me that in the current round of publicity, nobody is mentioning The New Adventures of Abraham Lincoln. McCloud has worked in color before and done a graphic novel before and it didn’t set the world on fire. This new book is being hyped as the first extended fictional work since McCloud’s Understanding Comics and its sequels. Having read Lincoln, I have to say that I approach The Sculptor with a certain amount of skepticism.

As Scott McCloud says, he has a big target on his chest regarding his latest book. Could it possibly live up to expectations? Well, nothing lives up to some people’s expectations. Does it prove to be a satisfying read? Yes, it does. It’s too easy to say that this book or that book does not rate for this or that reason. At the end of the day, The Sculptor is a fun read. You can read my take on it here: http://comicsgrinder.com/2015/02/02/review-the-sculptor-by-scott-mccloud/

Mark, if I read correctly, The New Adventures of Abraham Lincoln was published before the “Comics sequels”. And even McCloud names it “a noble failure”. So OK, McCloud isn’t perfect but he has done incredible books too. Zot! is really nice to read as well as the Comics series. So I’m really eager to read The Sculptor and the Lincoln book too (just to see what a failure McCloud would look).

Source: http://www.scottmccloud.com/2-print/older/abe/index.html

Comments are closed.