Luc Bossé is a cartoonist and graphic designer from Montreal and founder and editor of Pow Pow Press, a French Canadian graphic novel publishers. In 2015, Luc launched a crowdfunding campaign to translate four books and begin publication in English. I’ve spoken with Luc about his career, colour printing, where Pow Pow Press is going and about the difficulties in moving from the French to the English distribution models.

Please note that this interview was conducted in French and was translated in English.

—

Philippe Leblanc: For those readers who may not be familiar with you and your work, can you tell us a little bit about yourself?

Luc Bossé: I’ve been a fan of comic books since I was kid. I started reading European classics, like many kids at that age like Gaston Lagaffe, Astérix, Philémon, among others. I was doing some drawings and short comics when I was 12 years old, nothing substantial, but it was fun. I put that aside for a number of years though. I was reading less comics and had that misconception that comics were just kids stuff. I worked as a graphic designer for years and a friend introduced me to a new wave of European comics, mostly things published by L’Association. I dove right back into comics and thought it was fascinating how comics had changed, how the audience for comics had changed and matured. I was pulling in paycheck after paycheck in comics. I also started doing comics again, I dusted my pens and started a blog called BD de cuL. I know the popularity of blog have faded in the last few years, but they were really popular a decade ago. Anyway, I was still working in advertising doing graphic design, but I really liked the dynamic of blogging and making comics. It was very train-of-thought without any form of self-censorship, when you go back to the beginning of the blog today, there’s some stuff that I’m pretty ashamed of in there. But overall, it wasn’t really serious. I was getting bored of working in advertising and wanted to see what else I could do. I wanted to find a way to push myself further, to push comics further. I started self-publishing collections of my blog and stapled fanzine. Step by step, I met people working in comics and progressively I started expanding what I was doing.

I never had an epiphany where I thought “I will be a comic editor and publisher”. I just got caught in it. That’s me in a nutshell, a graduate in graphic design from Laval University who got tired of telling other people’s stories and started telling his own instead.

PL: How were your first comics and fanzine received? There must have been feedback that was good enough for you to keep pushing in comics.

LB: On the blog, I received positive feedback. The community of blogs and readers was still pretty substantial at the time. Blogs are still around, but the readership isn’t as wide as it once was. Both in the comments and in the site traffic, you could see that there was an interest. Even with this in mind, you can never really be sure that there is enough of a readership to sustain this as a career. Making the leap to comics full time was mainly my own desire to take that chance rather than substantial data showing me I could make this a viable profession.

My first event of printed comics I attended was in the basement of a church during the “Off-FBDQ“ (Festival de Bande Dessinée de Québec) on St-Jean Street in Quebec City. I had printed comics and my dad bought ten. I couldn’t tell if it was to encourage me or if it was pity. Anyway, two or three people I didn’t know bought my stuff. It’s still not with two or three books that you can sustain a career in comics, not even with a thousand. I just followed my gut feeling, I had to do comics. I’m not particularly stressed in life and I thought I’d pursue this as far as I could. The publishing company was also something that happened organically. It was never my goal to begin with.

PL: You started Pow Pow Press in 2010?

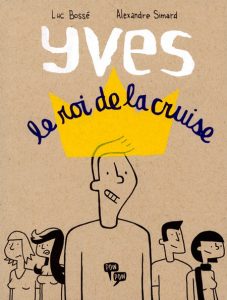

PL : After those two original books (Yves, le roi de la cruise & Apnée), what did you do? How did you use this as a jumping point for the other projects?

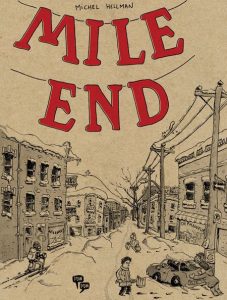

PL: You sold so many of Michel Hellman’s Mile End that you decided to cool things off by publishing his new book about the Northernmost area of Quebec, Nunavik? This way, it will be a top seller in an area with extremely low population density and you won’t have to reprint it so often.

LB: Who knows, it might be a big hit up North. Nunavik came out in May with a first print run of 2000 but we already sold out of it and it has to go into a second printing already. It’s a good problem to have, we didn’t think we’d have so much demand. Michel’s books are excellent, his style evolved and it`s a much more cohesive and interesting read. It will be one of our next English publications as well.

PL : You launched a Kickstarter campaign to fund the translation of books into English. Mile End by Michel Hellman, Vampire Cousins by Alexandre Fontaine Rousseau & Cathon, Vile and Miserable by Samuel Cantin and For as long as it rains by Zviane. What was the spark that made you want to go into the English language market?

LB : It’s a precise moment I still remember. I was at the Festival de Bande Dessinée de Québec and I was talking with another cartoonist from France. He said he really liked Vile et Miserable and we got to talking about entering the European market. He said that the book might be too hard for the French public and that the book might have to be translated in a cleaner European French. It really irritated me that people would think I’d need to translate a book from French to French. It’s nonsensical. There’s regionalism in Canada for sure, but we don’t translate European French books to Canadian French. We take the original version and read it, warts and all. We just figured, maybe the English market would be easier. Zviane and Samuel thought it was a great idea so we went ahead with it.

Being in Montreal means that a lot of events such as Expozine and MCAF are mostly bilingual so there was a proximity that made English easier than crossing the Atlantic. My opinion has changed since, but at the time, it made the most sense. I thought we could become a bilingual publisher and do our books in French and English.

LB: There are not a lot of people in Quebec, or in French Canada, with an interest in comics. The English market is much bigger but it also means there’s more work offered in English. Our distributor did inform us that the numbers of Graphic Novel sales are better in French than in English, but it’s expanding. In French, you have a lot of extremely successful series that act as a gateway for the whole medium, like Michel Rabagliati’s Paul for example. But there’s a lot of English publishers who are doing extremely well, like Drawn & Quarterly or Fantagraphics. There are also celebrities that have huge draws, such as Chester Brown, Seth, Chris Wares, Adrian Tomine, Julie Doucet, that drives up sales too.

Publishing in English meant I had to go back and learn the distribution business almost from scratch. Everything is different.

PL : I don’t think you’ve distributed in comic book shops as they get their stock mostly from Diamond Distribution. I’ve seen Pow Pow books in both independent and chain bookstores’ graphic novel sections. How has your experience been in terms of distributing in the North American market?

LB : We had a fairly successful crowdfunding campaign, and were able to print our books. The challenge then became how to we get those books out in bookstores. Finding a distributor has been complicated. For Diamond, you need a fairly large print run to make it viable. We`re not at a point where we can just print upwards of 10,000 books to distribute. I asked the owners of Drawn & Quarterly what would be a good distributer based on our size and they directed us to LPG (Literary Press Group). But to become a member of this group was much harder than I thought. We only had four books which hadn`t been distributed in English before; they only sold on Kickstarter or online. The history of our French publications made it so we were able to demonstrate that we were a serious business. I get it, they’re not interested in working with someone who produces only one book a year. They want to see a growing catalogue and people that are committed to making that happen.

Some of the major differences with the French market was needing to have a catalogue with set release dates, have things planned far in advance, have accurate specs for our books and have our books warehoused at least a month before the actual release date. Whereas our French distributor could turn around and have a book on the shelves within a month. That’s obviously not the best way to do it as you need enough time to market a book to bookstores, but it’s not unheard of. In the English market, there’s no way we can pull that off. The market is bigger, the books need to travel farther and it needs more planning. The advantage of having an existing catalogue in French is that we can look ahead and see what we`re going to be translating next and plan accordingly.

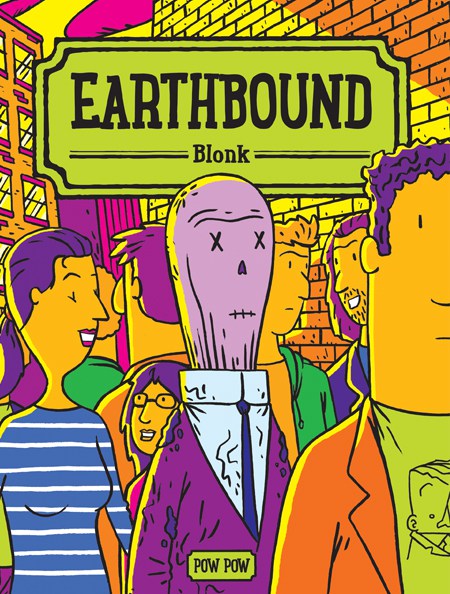

LB: Yes, and an advantage is that some of the cartoonists can work in both languages. Samuel Cantin translated most of his own work, same with Michel Hellman. In a way, it is barely translation, it’s a rewriting of the same work, by the same author. Samuel adapted some of the jokes for the English version of Vile & Miserable, it was natural for him to do that. Our next book Earthbound, when Blonk presented it to me it was in French as 23h72. He had started it in English because he wanted to shop English publishers. So it’s almost natural to have our books be in English and French. Our cartoonists are bilingual; they consume English and French culture and their influences are from those two languages at once.

PL: Now that you effectively have two streams of publishing, would you consider doing an English book first that would later be translated in French?

LB: I think for the moment we’re going to keep doing new books in French and translate our back catalogue, but I’m really open to being pitched English projects. It would be great if we could do both at once and have the same book being released at the same time in French and English, that would also be neat. I’d like to do an English to French book.

There’s also a limit to translating our own books. Some books we won’t be able to translate. We have the French version of Julie Delporte’s Everywhere Antennas, but that book was already released in English by Drawn & Quarterly so that’s off-limits. We have the latest Lewis Trondheim in French that has already been planned in English with another publisher. The alignment will never be entirely perfect for each book.

We also have a few books that I think are “untranslatable”. Motel Galactic is in three volumes and it’s filled with specific French-Canadian pop cultural references and written in a particular jargon that makes it pointless to translate. It would lose it’s charm and it wouldn’t be interesting to read. Too much changes in reference to culture, politics and events. The language used would make it hard to replicate. I think this book is condemned to stay within the confines of French Canada. We may send some in Europe, but I doubt it will be a bestseller there. Jokes about Regis Labeaume really wouldn’t connect with a European audience.

LB : I’ll be able to answer that question a year from now. We just started distribution in Europe. We met our distributor in 2012, the same distributor for L’Association, and we’ve been preparing for a while, but it’s still really fresh. I’m not sure all of our titles will be as successful as here, but I have a good feeling. It’s always hard to tell. Even the English books, because they weren’t officially new when we started distribution, they ended up being considered as back catalogue items. We never marketed a fully, 100% new book in English yet. I’ll be able to know more next year.

PL: Going back to translation, I believe you hired Helge Dascher to translate your first round of books. How did that work with having some of your cartoonists doing some translation already.

LB: She translated For as long as it rains and she did Apnée and Art Wars. She also helped to review all the books to ensure they all made sense. Helge did a great job, even Zviane said her book turned out to be better in English than it was in French. Working with her is a pleasure. Translating comics is not an easy job. You have to understand words, context, continuity and space on your page. We’re so happy to have such a fantastic translator.

PL : I can’t help but notice that your own work isn’t part of these translated books, nor are they scheduled to be translated anytime soon. Why is that?

LB : I don’t know. Maybe I could translate them. I feel like my latest book Comment faire de l’argent would be hard to translate. Perhaps I’m wrong. My first reflex is to look at other people’s books before my own. Since I’m working on the sequel to Yves, le roi de la cruise, perhaps I’ll wait until after we’re done with that. I could talk to the author, he could probably translate most of his own work too, come to think of it. I’m tough on myself. I don’t feel my drawings are up to par with what you would consider good work in English. Maybe I’m too critical because I’m editing myself. Maybe at some point eventually, but I don’t think it’s a priority. Alexandre Fontaine Rousseau is helping me with communications in English. He’s doing our bilingual press release. When we were talking about the second Kickstarter campaign and were picking out the books to translate, he recommended Yves, le roi de la cruise, but I wasn’t convinced. In time it will, but comics always take a long time.

PL: Why aren’t you satisfied with your art?

LB: I’m rarely happy with my own drawings. Sometimes I am, but I’m focusing more on the reading, on the flow of the drawings. When looking at a page, I’m constantly looking at whether the action is comprehensible, will people tumble into a page because something doesn’t work and they can’t proceed or understand what’s happening. I’m approaching it as a graphic designer. Clarity is important, easy to decode. Having scenes end at the last panel of a page and not a third of the way through a page, that to me is more important than the beauty of a drawing.

PL : You mention ending scenes at the end of a page. You publish work by Pascal Girard and I’m reminded of Petty Theft whose flow was often interrupted at various point in a page with one scene ending and something new starting. It’s interesting that you think flow is so important.

LB: Pascal works differently as he cuts his panels in a page and he draws a panel until he’s satisfied with it, then will go over the entire book and add or remove panels to make sure the book is to his satisfaction. I work my pages together calculating when the pages will end and what I need to put in each panel to get to the end I want. They’re just different ways of working really. But Pascal, you know…he’s just not that good… I’m kidding Pascal is a great guy and a fantastic artist.

LB: It truly is a cost issue. Printing colour is much more expensive than black & white. Earthbound (23h72) is in colour and, in order to make it worthwhile for the printing cost, I need to have a larger print run. The larger print run decreases the cost per copy, but also means I have more copies of the book to sell, which is more risky. It also makes the cost of the book itself more expensive for readers. Earthbound is $25 and Je vois des antennes partout is $27. That’s starting to be expensive and prohibitive for new readers. It’s relative, of course. I could just have my books printed in China and lower the costs, but I don’t want to do that. We also weren’t presented a lot of colour projects. Working in colour is often longer so some artists aren’t interested in doing that extra work, especially since the returns on investment aren’t always worth it. You don’t make a lot of money in comics. We don’t have a lot of bestsellers and it’s a small market. Part of our reasoning in printing English books was to give us access to a bigger market and make more sales, so we could generate more profit to pay our artists better, thus allowing them to spend more time on their projects, or even do longer projects. There are arts grants, but not everyone has access to those and it’s not always a guarantee. Black & white really comes down to money. We were able to circumvent that a bit with Motel Galactic and Ping Pong. They’re both in black & white with one additional colour, but the costs were higher. If we had a larger print run it would reduce our cost per copy and eventually the cost to customer. Even the aesthetic of the book with the flap adds cost. We care about making appealing books and all of those elements add cost.

PL : I really like the aesthetic of the books you publish, all are roughly the same size with the same paper stock and cardboard-like cover with a flap on both sides. Why did you choose to keep to that aesthetic for your books?

LB : I think it’s the graphic designer in me that wanted to have a standard that could be modified for each new book. But I think the real reason was that I wanted all of our books to be recognizable. You see the format and cardboard stock cover and you recognize its Pow Pow’s books. When people like one or more of our books, it’s easier to find them in bookstores. And the ultimate goal is that bookstores and comic shops also recognize them and either put them together, or can direct people toward our books. I felt very proud the day I walked in a bookstore in Quebec and all our books were side by side on the same shelf. It felt like a victory. There’s also a collectable aspect in comics that’s undeniable. Having our books done in the same style I think taps into that. Having a few of them on your bookshelf and knowing you’re missing two or three, it’s annoying. If I could go back in time, I may have numbered all of our releases. Joking aside, we were aiming for recognizability.

The size is also good for people traveling. You can easily take them with you on the bus or a flight. It wasn’t planned originally, but we’ve had lots of comments about that. The size and cardboard stock make them look nice. When we go to shows and we have all of them on the same table or on display, it looks classy. When books are different sizes and formats, it’s harder to have that same unity.

We also wanted to have something that was an object that looked nice. There’s this digital competition we can’t ignore so if people are going to buy a book, it better look nice and interesting.

PL : What’s the future of Pow Pow Press? Where do you see it in 5, 10 years from now.

LB : Europe and North America, we’re coming. The future is doing a bigger volume so I can pay our cartoonists better so they can do more work. Passion is great, but you need to be able to make a living. There are projects that are slowed down right now because of that. I’d like to be able to afford to provide our artists with advances so they can take three months off and focus solely on their work, but it’s impossible right now. In the future, I’d like to do that.

Fall 2016 is hard because we’ve sold out of a few books so we need to reprint some and that can be tough. Having five books sold out is a great problem, but it’s pricey to reprint stuff. Since we’re putting the money up front to reprint, that means the return only comes when sales happen and that can take some time. It’s an investment in “maybes”. Maybe I’ll see the money back soon. If we knew Nunavik would sell as well as it did, we would have printed more from the start and lowered our per unit cost. But we didn’t know, so we went conservative on numbers and now we’re sold out of a new book that’s still in high demand. It’s a risky business. There’s also returnability in bookstores. They don’t buy the books ahead of time; they sell it to people or they return it to you. I was naïve at the start and now I’ve learned. Maybe I wouldn’t have started this business knowing all of this, but now that I know, let’s put this experience to work and make great books in English.